While the recent G7 commitment to “decarbonization” by 2100 is a positive step, accelerated melting of the Arctic suggests a need to step up the transition to a sustainable energy future.

A Canadian climate forum on “The Unravelling of the Arctic,” held on Earth Day, April 22, in Ottawa, featured prominent scientists who discussed how warming in the Arctic has consequences for the entire planet.

Martin Sharp from the University of Alberta has spent every summer since the 1990s studying glaciers in the Canadian Arctic, and is a lead author for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on the “cryosphere” — the frozen water part of the Earth system. His work indicates that Canada’s Arctic islands are a global hotspot for glacier loss. Shrinkage of glaciers began around 1950 and accelerated in 1990, with all portions of the Canadian Arctic now experiencing summer temperatures above freezing.

Dr. Sharp has discovered a new phenomenon that helps explain this accelerating loss. As glaciers melt, water drains downward and refreezes into a relatively impenetrable ice layer that blocks drainage deeper into the glacier, forcing melt water to run off to the sea instead. According to a study in Nature by Sharp and co-authors, between the periods 2004–2006 and 2007–2009, loss of glacial ice from Canada’s Arctic tripled from 31 to 92 billion tonnes per year. Canada’s Arctic islands contain one-third of the world’s land ice (not counting the much larger Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets). Loss of Arctic glaciers makes Canada the third-largest contributor to global sea-level rise. Each 300 billion tonnes of water released from land ice raises global mean sea level by one millimetre.

A global problem

The ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are also disappearing. A study based on recent satellite data comparing the periods 2003-2009 and 2011-2014 shows that annual melt of the Greenland ice sheet increased by a factor of 2.5, and melting in western Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula increased by a factor of 3. Because ice is accumulating in eastern portions of Antarctica, net Antarctic ice loss is around 125 billion tonnes per year, only slightly greater than annual ice loss from Canada’s Arctic islands. Loss of the Greenland ice sheet is far higher, at around 375 billion tonnes per year. The phenomenon first observed by Dr. Sharp in the Canadian Arctic of increasing run-off of melt water owing to formation of an impermeable ice layer beneath the surface appears to be occurring in Greenland as well.

Dr. Sharp notes that accelerated melting affects regions far beyond the Arctic. Loss of land ice and rising seas increase flood risks for low-lying countries such as Bangladesh. When glaciers disappear, the darker ground underneath is exposed and absorbs more sunlight and heat, altering regional and global climate. Hydropower potential in the low Arctic is reduced. Pollutants such as DDT, lead and mercury previously deposited in Arctic ice through global atmospheric circulation are remobilized when ice melts. Glacier run-off is nutrient-rich and sustains feeding grounds for seabirds and marine mammals, so increased melting may bring temporary benefits but poses longer-term concerns.

Much scientific attention is currently focused on “albedo” — reflection of solar radiation from the Earth’s surface back into space. Higher albedo maintains cooler temperatures; lower albedo means warming. With warming, snow grains increase in size and reflect less radiation. Microorganisms grow on the surface of the ice and snow, and produce dark pigments (red, green, purple) to protect themselves from UV radiation. Darkening of the ice cap represents an important climate feedback. Melting ice exposes black carbon and other impurities that reduce albedo and contribute to further melting. Arctic Council nations recently agreed to restrict emissions of black carbon in light of its role as a short-lived climate pollutant.

Permafrost as planetary thermometer

Antoni Lewkowicz, a University of Ottawa professor and president of the International Permafrost Association, spoke on the topic of permafrost, defined as earth material whose temperature remains below freezing for at least two consecutive years. Unlike glaciers and sea ice, permafrost occurs below the surface and is measured by temperatures in boreholes, rather than by remote sensing techniques.

Permafrost underlies nearly a quarter of the Earth’s land surface. Many people live on permafrost. Much of the world’s natural gas supply comes from permafrost areas in Siberia and Alaska. Permafrost provides poor support, so pipelines must be built aboveground, highways need a thicker gravel base, and building foundations must be specially designed to avoid thawing of underlying frozen ground.

Dr. Lewkowicz calls permafrost a “planetary thermometer that always tells the truth.” Permafrost in Canada is rapidly disappearing. Boreholes sampled in the late 1970s in anticipation of construction of a gas pipeline along the Yukon portion of the Alaska Highway all showed warming when re-sampled in 2011-2012. Permafrost had completely vanished from 50 per cent of this area.

Permafrost has broader climate implications. It contains twice as much carbon as the Earth’s atmosphere and emits the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide and methane when it thaws. Methane is of particular concern — the IPCC puts its short-term (20-year) global warming potential at 72 times carbon dioxide. Dr. Lewkowicz says that carbon dioxide emissions will likely dominate over methane, but adds that “huge quantities of carbon are currently locked up” in permafrost and “there won’t be a reverse gear if we don’t act.”

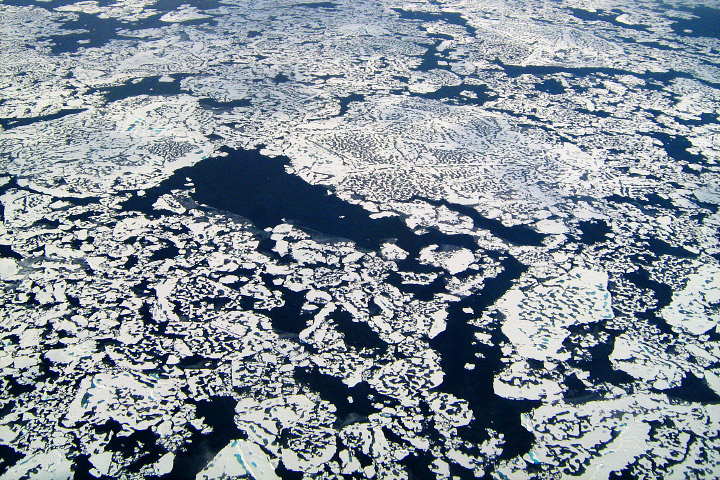

Tracking Arctic sea ice

Bruno Tremblay of McGill University spoke on Arctic sea ice. It has been declining at around 10 per cent per decade since 1979. Before then, thick sea ice accumulated each year (especially along the Canadian coastline) and resisted wind motion, so that minimum Arctic sea ice around at the end of the summer was largely determined by temperature and amount of sunshine. Today’s thinner sea ice is blown about by winter winds, mostly away from the Eurasian coastline towards Canada. The first-year ice that forms in its lee is more vulnerable to melt, with greater areas of melt ponds and a darker surface that absorbs solar radiation. Changing wind patterns in the Pacific Ocean are also bringing more warm water through the Bering Strait, causing ice thinning in adjacent parts of the Arctic Ocean.

Although the Canadian coast has the oldest and thickest sea ice in the Arctic, models suggest that it will largely disappear by mid-century. Dr. Tremblay points out that female polar bears need ice to hunt seals and feed their cubs when they emerge from their dens. Current trends point to a total loss of their sea ice habitat by 2040 to 2080.

In terms of the wider-scale impacts of a warming Arctic, Dr. Tremblay points to the temperature anomaly currently prevailing in Eastern Canada. With the reduction of the heat gradient between the Equator and North Pole, the jet stream is meandering and the East Coast is experiencing colder than normal temperatures. He notes that the science behind this phenomenon is still under debate.

The Gulf Stream and climate change

Dr. Tremblay says that melting of sea ice would not provide enough fresh water to shut down the Gulf Stream, but melting of the Greenland ice sheet could do this. The interaction between the strength of the Gulf Stream (or Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, AMOC), melting in Greenland, and climate in the North Atlantic and adjacent parts of North America and Europe, is a hot scientific topic.

One study indicates that the AMOC fell to its weakest level in the past thousand years starting in 1975, with a partial recovery after 1990. Another suggests a recurring scenario. Melting in Greenland releases large amounts of fresh water, dilutes the warmer and heavier salt water flowing northward in the AMOC, prevents it from sinking, and slows the return southward current along the ocean bottom. This weakening of the AMOC then cools the North Atlantic, reduces fresh water inputs from melting in Greenland, and allows the AMOC to regain strength.

This scenario implies that the anomaly of a colder-than-normal climate in the North Atlantic and adjacent parts of Canada may continue for the foreseeable future. These areas could also experience significant temperature fluctuations (and perhaps more extreme weather events).

Meanwhile, Canada’s Arctic is undergoing some of the most rapid warming of any portion of the planet.

It is clearly time to rethink Canada’s non-renewable-resource-extraction-based economy. Perhaps the North can be a testing ground for the economic diversification and green job creation measures that will be needed across the entire country.

Ole Hendrickson is a retired forest ecologist and a founding member of the Ottawa River Institute, a non-profit charitable organization based in the Ottawa Valley.

Photo: Methane leaking through the cracks. Credit: NASA’s Earth Observatory/flickr