Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporting member of rabble.ca.

The Institute for Research on Public Policy has published a very interesting overview study on the resuscitation of “industrial policy” in economic policy circles. It points out that industrial policy levers are used widely by countries around the world — despite hypothetical efforts (through trade deals and other institutions) to limit their application. The traditional Walrasian critique that government efforts to “pick winners” are wrong-headed and promote inefficient outcomes is holding less sway — all the more so in light of the deindustrialization, private sector underinvestment, and persistent trade imbalances that seem to be the legacy of Canada’s relatively laissez faire approach to industrial policy since the 1988 Canada-U.S. free trade deal. While I don’t agree with all of the IRPP report’s findings, it is a useful contribution to a debate that needs to happen. Other researchers in Canada are also looking in a more serious and balanced way at this set of issues; I especially follow the work of David Wolfe and Daniel Poon.

In fact, I prefer not to even use the term “industrial policy,” which seems to automatically convey images of large-scale “smokestack” industries and large government subsidies. In fact, there are all sorts of sectors which are worthy of a wide range of pro-active interventions by government (not just subsidies) aimed at expanding their relative footprint in a particular jurisdiction. The reason for government getting involved is the important spillovers felt in other areas of the economy (investment, exports, productivity, and incomes) from a stronger domestic presence of desirable tradable industries. This includes high-value tradable services sectors, too (like business services, transportation, tourism, and even specialized public services like higher-level health care and education facilities which provide services to wider populations and hence have similar characteristics to other “export-oriented” sectors). In my work for the Alternative Federal Budget and other outlets on this issue, I have tried to use the term “sector development strategies” rather than industrial policy.

Another counter-argument to pro-active sector strategies is the claim that manufacturing employment is declining universally, so there is no point trying to stand in the way of it. There are indeed strong reasons why manufacturing tends to account for a smaller share of total employment over time: faster-than-average productivity growth, a gradual shift of demand to services (due to a higher income elasticity of demand), and others. But those trends don’t explain why manufacturing output should shrink in absolute terms (as it has in Canada since 2006). And it is clear that Canada’s share of manufacturing has shrunk markedly over the last decade — relative to global manufacturing output, and relative to our own purchases of manufactured goods. For example, Canada’s trade balance in manufactured products deteriorated from approximate balance a decade ago, to a large and chronic deficit of around $100 billion per year today. By this measure, Canada’s deindustrialization during the high-loonie era has been uniquely dramatic (and painful), and cannot be attributed to a universal trend.

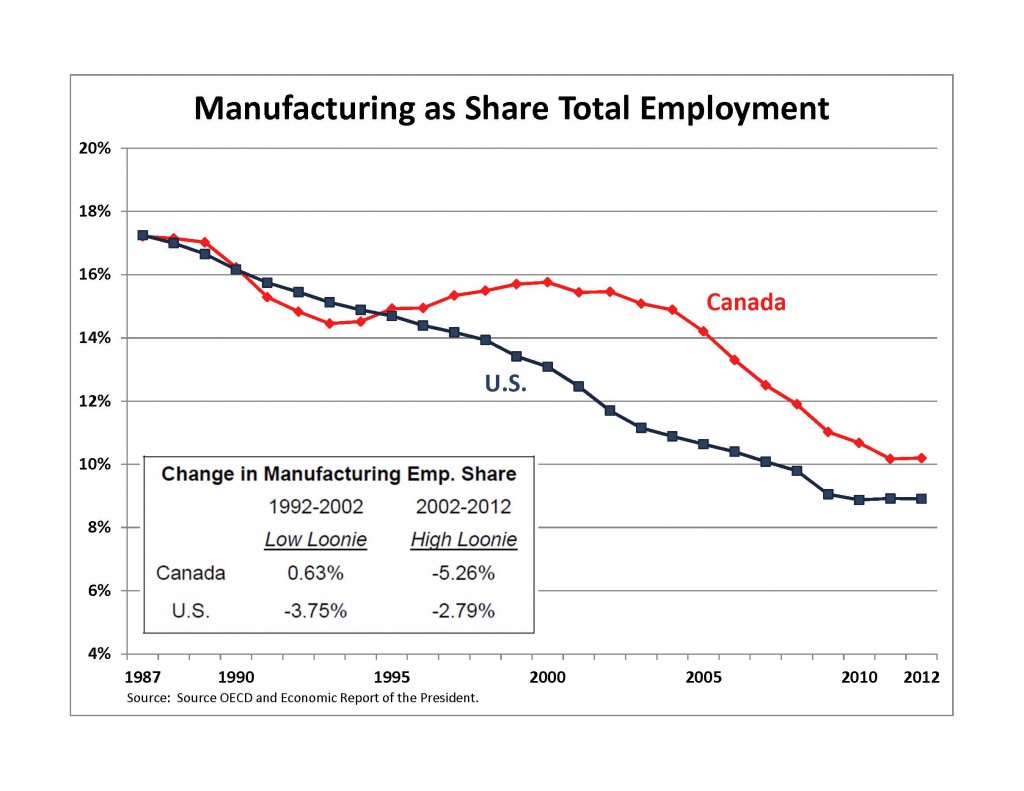

More evidence on this score is provided by the above graph, which plots manufacturing employment as a share of total employment in Canada and the U.S. During the low-dollar 1990s, Canada created manufacturing jobs slightly faster than the growth in the overall labour market (while the U.S. was deindustrializing). Since 2002, however, when the global commodities boom (and foreign investors’ hunger for Canadian petroleum assets) took off and the dollar appreciated, Canada has lost manufacturing jobs (relative to total employment) almost twice as fast as the U.S.

And compared to some other OECD countries, our relative share of manufacturing employment (now just above 10 per cent) is low. Manufacturing accounts for 20 per cent of employment in Germany, and 17 per cent in both Japan and Korea. These countries also face the same “inexorable” trends in manufacturing employment as Canada, and the same pressure from low-cost emerging exporters — yet they have managed to hang onto a higher proportionate share of these high-productivity, high-income jobs.

I think the strategic importance of manufacturing (and other high-value, export-oriented, innovation-intensive sectors) is coming to be better appreciated by policy-makers who were unduly influenced by the “hands-off” arguments of recent decades. Hence this is a fruitful time for progressives to be fleshing out our arguments for the sorts of sector strategies that could play an important role in coming years.

Jim Stanford is an economist with CAW.