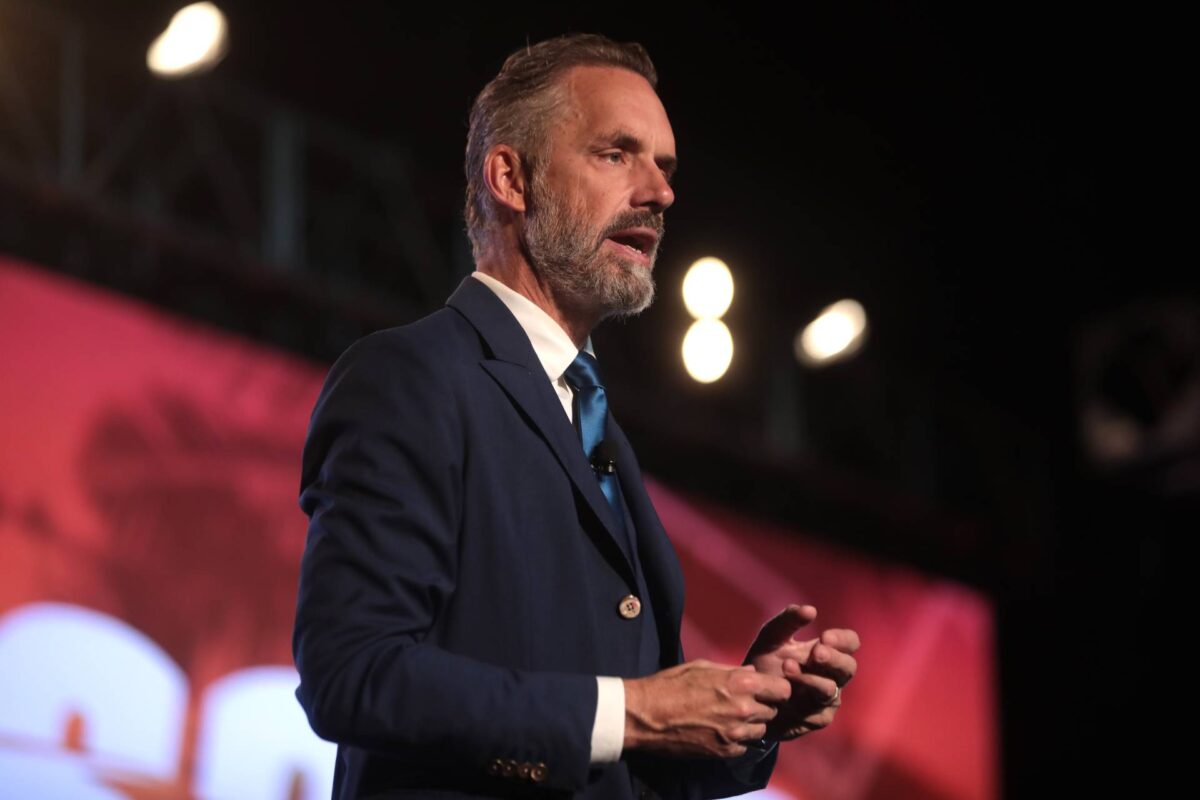

The Ontario Divisional Court recently released its decision on Jordan Peterson’s challenge of the College of Psychologists of Ontario’s order that he complete a coaching program on professionalism in public statements. The Court’s decision, which upheld the College’s order, has generated a fair bit of commentary in the media, much of which argues that the order and decision are assaults on Peterson’s freedom of expression, or will empower “woke” organizations to curtail individual freedoms.

However, I look at the matter from a different lens. While I may have the right to freedom of expression, how I exercise that right may have implications. For example, at a very basic level, if someone expresses a strong opinion on one side of a subject, they may risk relationships with family or friends who have strong opinions on the other side. In the case of Jordan Peterson, the potential implications are that the manner in which he is choosing to exercise his right to freedom of expression may impact on the privilege of being licensed as a clinical psychologist by the College of Psychologists of Ontario.

License to practice – A privilege not a right

You may note that I referred to being licensed as a privilege; that is by design, as there is no right under the Charter to practice any particular profession. Instead, being licensed to practice any particular profession is a privilege, and many would argue that it imposes certain responsibilities upon those who are licensed. Further, as a self-regulated profession, the College of Psychologists of Ontario has a mandate to regulate the profession in the public interest, and to that effect it has developed Standards of Professional Conduct and adopted the Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists.

This Code of Ethics provides that “psychologists acknowledge that all human beings have a moral right to have their innate worth as human beings appreciated,” without regard to factors such as ethnicity, religion, sex, gender, sexual orientation, “or any other preference or personal characteristic, condition, or status.” The Code also provides that “psychologists do not engage in unjust discrimination based on such factors and promote non-discrimination in all of their activities,” and that psychologists must “Not engage publicly … in degrading comments about others…”.

The comments that formed the basis of the complaints against Dr. Peterson included comments on a podcast in which he commented on air pollution and child deaths by saying “it’s just poor children…” and tweets in which he (presumably purposely) referred to actor Elliot Page as Ellen Page and called the doctor who performed their top surgery as a “criminal physician,” as well as referring to a municipal politician who uses they/them pronouns as a “thing”. It seems pretty clear that those public statements fall afoul of the provisions of the Code of Ethics mentioned above. In fact, the comments about Elliot Page resulted in Dr. Peterson’s Twitter account being temporarily suspended for breaching rules against hateful conduct.

Not in my professional capacity

A primary element of Dr. Peterson’s argument against the order was that he was not making those comments in his capacity as a clinical psychologist, but that they were rather “off duty opinions.” As such, he argued that the comments were personal behaviour that should only attract the attention of the College if it undermines the public’s trust in the profession as a whole or calls his ability to carry out his responsibilities as a psychologist into question.

The Court did not accept those arguments, noting that there is a difference between what a person might say or do in personal conversations with friends, and making public statements to broad audiences through podcasts or social media. It also pointed out that Dr. Peterson still referred to himself as a clinical psychologist in those forums and also considered himself to be “functioning as a clinical psychologist ‘in the broad public space’ where he claims to be helping ‘millions of people’ and as he put it, he is ‘still practicing in that more diffuse and broader manner.’”

The Court commented that being recognized as a health professional when making those comments added credibility to the comments, and that because of that, someone who is licensed as a clinical psychologist (or a member of any other regulated profession) may be held to a higher standard of conduct.

In the end, the Court wrote that “Dr. Peterson cannot have it both ways: he cannot speak as a member of a regulated profession without taking responsibility for the risk of harm that flows from him speaking in that trusted capacity.”

What next?

So where does that leave matters? From a legal perspective, Dr. Peterson has indicated that he will appeal this decision, so it will be interesting to see how the Court of Appeal deals with this issue. With respect to those who are concerned that this decision will have a chilling effect on what licensed professionals can say or do, I would counter that being subject to a code of ethics or having to be more responsible and thoughtful in how one expresses oneself in public forums is part of the package one accepts in exchange for the privilege and benefits that come with being a licensed professional.

In the end, though, we all have rights, but we have to recognize that we do not get to exercise those rights in a vacuum. As long as Dr. Peterson chooses to maintain a license as a clinical psychologist, he has to abide by the Code of Ethics that the profession requires of its members. Nobody is forcing him to be a member of the profession – to paraphrase one of his tweets that was complained about “You’re free to leave [the profession] at any point.”