You can change the conversation. Chip in to rabble’s donation drive today!

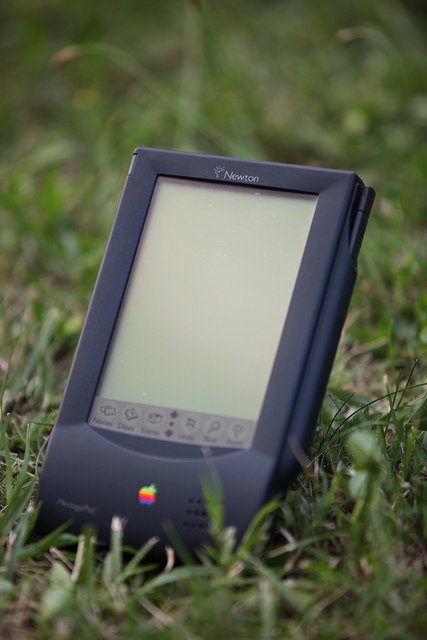

Just after Christmas I got a new mobile device on sale. It’s about the size of a Nexus 7 tablet, has a touch screen, comes with a stylus and can recognize handwriting and even introduces geometric perfection to the shapes I draw on its six-inch screen. It’s called the Apple Newton MessagePad 120, a ghost from the past, and I remember why I loved it, all those years ago.

When it was introduced in 1993, the Newton MessagePad was the most high-profile member of the personal digital assistant (PDA) family. Its most notable and most often maligned feature was its ability to, sometimes, convert printing and handwriting into text. By the time the MessagePad 120 came along in 1994, many of the bugs had been worked out of the device and I used it as a note taking, project management and writing tool for consultancy work I did for the Ontario Science Centre.

Back then it seemed impossibly light and portable given its power. Now, placed next to my iPhone, it is an ungainly, slow brick with a dull, almost unreadable, unlit screen. Back in the ’90s I used it for almost everything, now I can use it for nothing. It doesn’t connect to my computer, talk to my phone or chatter with the Internet. It is as solitary as paper, but requires 4 AA batteries. I sold mine years ago when I was cleaning out the basement.

Then, a few days ago, I saw one sitting in an antique shop and snapped it up. The old magic is still there. The calendar app, for example, allows you to handwrite an appointment at the appropriate time during a day — then it turns it into text, in place. Draw a rough approximation of a circle, and the note app will smooth it out for you. Scribble through your text and it vanishes in a cartoon cloud.

Some of these interface tricks have been refined and sped up in modern smartphones, others have been forgotten. They serve only as artifacts of interface design paths abandoned by Apple and others when virtual keyboards, voice and multitouch replaced styli as the main ways we interact with small mobile devices. But, overall, the MessagePad was a remarkable bellwether for a new generation of personal digital assistants and then, with the iPhone, the screen-centric smartphone. Using it back then you could see and touch the future. It was a new paradigm for computing that would take two decades to mature. That’s an important lesson.

One other thing my reacquaintance with the MessagePad taught me — value is time-sensitive. When it first came out, the MessagePad 120 cost just over $600. I sold my first one in 2001 for $75. A few days ago I bought this one for a toonie.

Like this article? Chip in to keep stories like these coming!

Wayne MacPhail has been a print and online journalist for 25 years, and is a long-time writer for rabble.ca on technology and the Internet.

Photo: Bruno Cordioli/flickr