I don’t speak French. I wish I could but I can’t. Canada is a bilingual country and it was a mandatory course in my high school. I took two years of French in college, and once even hired a tutor for private lessons. Sure, I can still stammer out a few simple sentences in French and understand some of what I read and hear. But Vancouver is a long ways from Quebec. On the west coast, French is rarely heard and, shall we venture to say? — unnecessary.

Perhaps I’m lucky to be a native English speaker. English has become the dominant global language after all — in politics, business, science, IT, and higher education. It’s hard to be a global citizen without English, and most non-native speakers learn at least some English in school. Worldwide, 1.8 billion people use English, mostly as a second language. Native English speakers are still a minority in the world, at 335 million. They are outnumbered by native speakers of Mandarin, Hindi, Arabic and Spanish.

English is a Germanic language, along with most other European languages. French is still the traditional language of diplomacy, and is one of the working languages of international organizations like the United Nations.

German was a strong rival to English up until around 1920, because German-speaking countries used to be at the forefront of scientific disciplines. German is still the fourth-most taught modern language worldwide, after English, Spanish and French.

I love stats, so please bear with me. Forty per cent of the world’s population is monolingual. A large minority! — but still a minority. An impressive 43 per cent of people are fluent in two languages, while 13 per cent are trilingual. When we gaze up in wonderment at the elites, 3 per cent of the world’s population speak more than four languages, while less than 1 per cent speak five or more languages fluently. The latter are polyglots and I am in awe. How is this even possible?

Learning any new language is hard. Like, really hard. Even after you learn and practice the words and phrases, they still seem, well, foreign. The constant translating in your head from English slows down the process and introduces mistakes. The words and phrases just don’t come naturally, especially when you’re a monolinguist at the ripe old age of 50-something. Also, grammar. Weird sentence structures. Tongue-twisting pronunciation. And don’t forget that you need to memorize upwards of 5,000 words to be reasonably fluent, and far more if you want to play Scrabble in Spain.

The common wisdom is that kids pick up languages easily and the best time to learn is early childhood, because: “After age 11, centers in the brain responsible for language acquisition stop growing rapidly and language acquisition becomes more difficult.”

But there’s another school of thought: “Researchers think that, given the right study methods, adults may be as able to learn a language as children. The differences are how the language is studied, immersion versus memorization, and how the person continues to learn.” That entails things like commitment and motivation, multiple study methods, and regular and ongoing practice for years. Immersion is certainly ideal, so it’s best if you can live in another country for awhile or at least travel a lot.

I met a polyglot a few months ago. A young Russian called Max, now living in Vancouver. I’m not sure how many languages he spoke fluently but it was mind-boggling. Interestingly, he said that German was his favourite. At the time, I was actually trying to speak German with him — “trying” being the operative word. Why, you may ask?

My heritage is Dutch and my parents emigrated to Canada in 1950, marrying in Ontario in 1951. Sadly, they made a conscious decision not to speak Dutch in the home or teach their kids Dutch, for which I have always felt much regret. Nevertheless, we got exposed to Dutch as children from friends and neighbours and there’s still a certain comfort level in hearing that language. I recognize it instantly even if I don’t understand most of it. But as an adult, I came to seriously regret not being fluent in Dutch. It’s not exactly a commonly spoken language in Canada though, and there’s no courses at local community colleges. But there is in German — which has a close affinity to Dutch. I also have some German friends, including a good friend in Austria where they speak German. I am envious, because he also speaks fluent English and French.

So I decided to learn German. I began a year ago, and in my optimistic moments I like to think that my German is now almost as good as my French and getting progressively better.

Of all the Germanic languages, one of the hardest to learn may be, well… German. My Austrian friend told me this a few years ago but I scoffed. How hard can it be?! I knew a lot of words already — Kindergarten, Doppelganger, Angst, Delicatessen, Schadenfreude, Verboten, Ersatz!

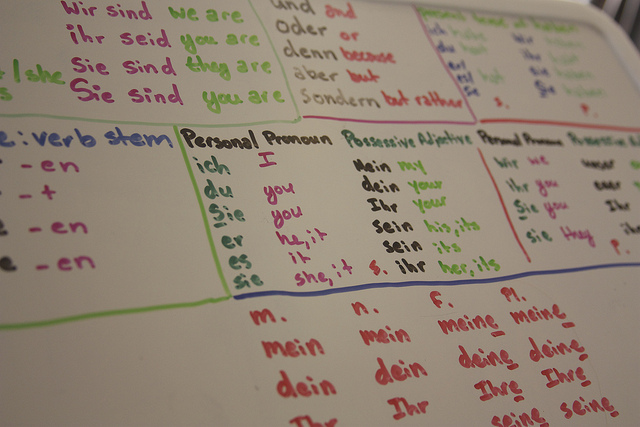

They say that English is the easiest language to learn and I know why. It has much to do with the words “a” and “the,” which are the ONLY two articles we need in English. (Yes, we also have “an” but the rule is so easy.) In German, depending on the gender and verb, you have to choose between ein, eine, einen, einem, einer, eines, die, das, der, dem, den, des, and maybe a few others I haven’t learned yet. Don’t get me started on the variations for the words “this” “that” and the other thing. Or how adjectives have to be modified according to gender. (I also won’t mention that key verbs are relegated to the very end of German sentences, which can be quite long. Good luck with your listening comprehension!)

The gender-neutral language battles we’ve successfully fought in English are basically impossible and unheard of in foreign languages like French and German, because everything is gendered. If you thought French was bad with its masculine and feminine nouns, try German with its three genders — masculine, feminine, and neutral. And there are no rules. The gender for the word girl is not feminine, but neutral: “das mädchen.” However, if you’re a teenage teacher, you must be either a male one (der Lehrer) or a female one (die Lehrerin); there’s nothing in between.

This is not the place to discuss the evolution of languages and how such difficulties came into being. That would take several encyclopaedic volumes. I have taken the liberty, however, of providing some specific suggestions on how to improve the German language to my Austrian friend. Unfortunately, he has not responded.

Becoming fluent in another language is a huge and challenging accomplishment, one I still strive for. I salute Max and all other polyglots. Really, how do you do it?! You have my profound admiration and respect.

Joyce Arthur is the founder and Executive Director of Canada’s national pro-choice group, the Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada (ARCC), which protects the legal right to abortion on request and works to improve access to quality abortion services.

Photo: Nina Helmer/flickr