It’s November, the time of year when we marvel at the glorious reds, yellows and oranges in our tree foliage and if we’re lucky we see some migrating birds, both a result of the seasonal chilling weather.

We’re reminded to check the batteries in our smoke and carbon monoxide detectors and, for most of us, to move our clocks back an hour.

As our communities become darker and colder, two things happen.

First, most local governments make moves in the form of a winter plan to shelter unhoused people and second, road departments announce big plans for snow removal and road salting.

Since mass homelessness exploded on the Canadian landscape in the 1990s, it’s been an uphill battle for advocates fighting for the most basic homeless services especially during inclement weather.

Municipalities have fumbled with approaches: experimenting with temperature formulas that will trigger the opening of warming and cooling centres, distributing sleeping bags and non-refillable water bottles, downloading the responsibility of shelter to volunteers from faith communities. For the most part these efforts smacked of ‘be thankful for what we’re offering’. Toronto’s first warming and cooling centres offered no cots or blankets, let alone meals. Toronto’s reliance for over 30 years on the faith-based winter-only Out of the Cold program created a forced nightly movement from one site to the next until the annual spring shut down, as if unhoused people suddenly were off to their cottage.

While these efforts saved lives, I believe an underlying and embedded prejudice towards the unhoused has driven government policies, charitable organizations’ response, the media coverage and at times even our own work as advocates.

Why do I claim prejudice? Because there should be a right to shelter on any night of the year, regardless of temperature or conditions of snow, ice, rain, or hail.

I confess that many advocacy organizations and frontline workers, me included, have used the weather as a special effect to garner political support and media coverage to pressure for shelter openings. In many cases these were textbook ‘Organizing 101’ lessons that won the opening of armouries, empty hospitals and civic buildings for shelter. These efforts also led to the concept of 24/7 respite shelters, the use of rent supplements to house people, and a federal homelessness program.

On the infamous day in 1999 that Toronto Mayor Mel Lastman called in the army to respond to a huge dump of snow, many of us were at the Board of Health with unhoused men and women who were begging for shelter. The weather backdrop and especially the shocking images of soldiers clearing our roads resulted in the precedent setting opening of the Moss Park Armoury as an emergency shelter.

In recent years it has been much harder to achieve shelter wins. I have seen a growing rigidity and callousness in the attention of local politicians and the decisions of city managers. At one point Toronto even outlawed the provision of survival supplies (sleeping bags, blankets, hot food) delivered by an Indigenous organization to people who were homeless claiming the service was enabling. City managers have resisted applying flexibility in the formula used to call weather alerts that would allow a shelter opening. Even worse, Toronto permanently cancelled its operation of cooling centres. During this year’s July floods that shut down the Don Valley Parkway, the City did not open an emergency refuge for the hundreds living in encampments, parks and ravines.

Back to cities’ predictable winter plans.

While climate change may reduce the need for snow clearing and road salting, robust winter plans to shelter homeless people are needed now more than ever.

This year, unique in their honesty, Toronto officials admitted its Winter Services Plan to respond to homelessness would not be enough to meet the demand for shelter.

Well, we knew that. Last year we sheltered 10,700 people. This year the number is 12,200. A shocking 223 people on average call the City’s own Intake line for a shelter space and are told none is available. It’s only going to get worse. Everywhere.

Encampments proliferate across the country and the intolerance towards unhoused people goes beyond Toronto. In an unprecedented move 12 Ontario Mayors have appealed to Premier Doug Ford (in fact, he requested they do so) to use the notwithstanding clause to suspend encampment residents’ Charter protected rights so they can be removed. Not only is there unavailable shelter or affordable housing for people to be moved to, it’s also widely understood in public health practices that in an ongoing pandemic it is bad practice to dislocate people.

How long can governments ignore the elephant in the room?

While Canadian politicians are reluctant to recognize the right to shelter, they are also negligent on the science and local experiences of the impact of climate change on vulnerable populations.

Like cities around the world, in the late 1990s Canadian cities faced the early signs of climate change.

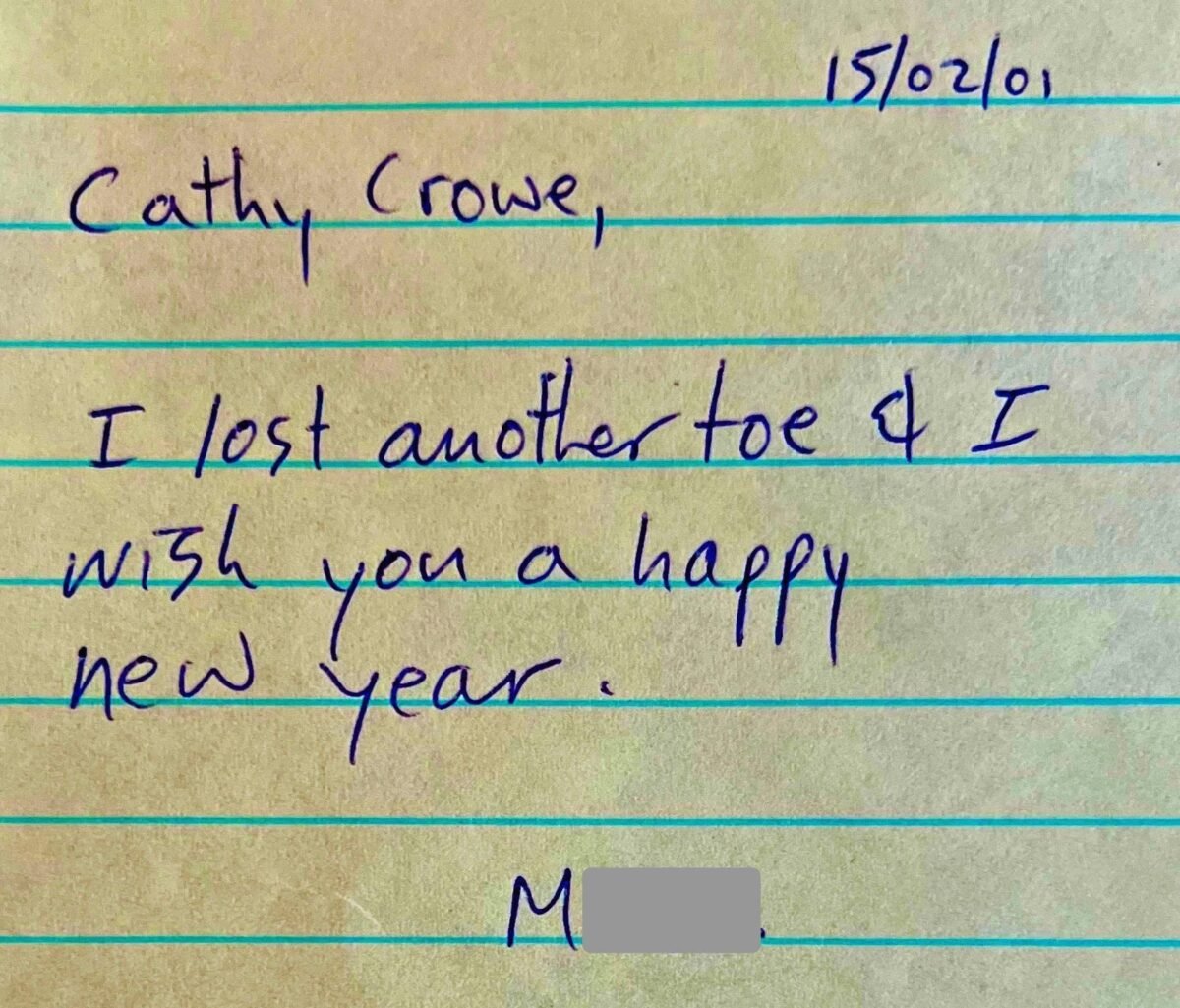

In Toronto, street nurses recognized that the homeless population was experiencing deleterious effects of extreme heat (heat stroke, cardiac incidents, dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, seizures, death) and extreme cold (hypothermia, frostbite, gangrene, amputations, death). We responded by advocating for more shelter spaces, cooling and warming centres and we shifted our work to include more outreach.

The 1996 inquest into the freezing deaths of three homeless men brought these issues to a national audience.

In 1998 Toronto Disaster Relief Committee’s (TDRC) issued an extreme warning: “Prolonged homelessness permanently harms people; ultimately, it can kill them by exposure, illness, violence or suicide.”

However, it was really the 1995 Chicago heat wave that killed over 1,000 people and the subsequent social autopsy that examined the political and social fabric that put climate change on our radar in Canada.

In Anatomy of a Heat Wave I examined the relevance of the Chicago experience:

“In 2005, at least six Toronto residents who lived in scorching rooming and boarding houses died during a heat wave. Toronto Public Health research has demonstrated that mortality rates are twice as high on extreme heat days compared to comfortable days. In recent years, Toronto has reluctantly operated cooling centres triggered by a tight temperature criterion. Only one of the centres has been open 24 hours, and only with pressure did the city begin opening centres on the first of a heat wave, instead of the third day. Infamously, several years ago, the city was caught running its 24-hour centre in a hallway without staff or food — just a sign, tables and chairs and a jug of water. No activities to pass the time, no meals, no healthcare on site, no cots to sleep on unless you’re about to pass out. No appreciation of what vulnerability can mean.”

(in Chicago) Lessons were learned. First, that accelerated death rates were linked to poverty, unaffordable housing, diminished social programs, and access to air conditioning. Second, that the most critical public health measures that can save life in a heat emergency are early warning systems, the immediate opening of neighbourhood-based cooling centres, outreach to seniors and vulnerable populations including vans to pick people up to take them to cooling centres, fan, and air conditioner installation programs, and reverse 911 calls, or automated calls to people who are vulnerable.”

In 2007 Tanya Gulliver, of TDRC did a fulsome deputation to the City as part of her Maytree Public Policy fellowship. It included both timely research and urgent recommendations.

She pointed out that: “Following that deadly summer of 2005, Toronto revised the existing heat alert plan and created a detailed Hot Weather Response plan and an Urban Heat Island Mitigation Strategy. These plans, while well intentioned, are inadequate and have not been fully implemented.”

Today we have the benefit of more science, yet we have fallen behind. The climate emergency, the homelessness emergency, poverty and food insecurity have all worsened since those early warning calls. Without adequate shelter, income and housing all forms of inclement weather hit unhoused people and poor people the hardest. There is no longer a day, week or month free from danger.