Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper, at an event touting the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), said:

“Let’s never forget from our earliest days, for our Aboriginal peoples and the first French and British traders, trade has always been responsible for the creation of wealth and opportunity. And of course, the same is true in the modern era…”

Did trade really create wealth and opportunity for Aboriginal peoples in Canada?

Before European contact, hundreds of birch bark canoes laden with trade goods ranging from beaver pelts to copper fishhooks passed up and down the Ottawa River every spring. The Kichi Sibi (“Great River”) was one of the continent’s major trade routes, linking the upper Great Lakes with the St. Lawrence.

Early Aboriginal trade

Stephen McGregor’s book, Since Time Immemorial: Our Story, describes trade between his Algonquin [Anishnabeg] ancestors and the Hurons [Wendat] as follows:

“The Wendat lived in permanent villages so that they could cultivate the land. Corn was the main staple of their diet, as well as beans and squash, which supplemented fish and some game meat… Contact and trade between the Kichi Sibi Anishnabeg and Wendat nations was inevitable. The Wendat required large surpluses of hides and furs from which to make warm clothing. The Wendat traded ample supplies of corn, tobacco and goods such as pottery with the Kichi Sibi in return for hides and furs… Over generations, the Wendat had refined their pottery techniques, making them lighter in weight but still durable. Wendat pottery was easier to transport on long journeys by canoe…”

Trade among Aboriginal peoples brought mutual benefit. But was “free” trade the norm?

No. The Algonquins controlled trade along the Ottawa River, levying “tariffs” on freight passing their “capital,” which was strategically located on an island with rapids on either side about 150 kilometres northwest of the current location of Ottawa. Their island capital also served as a manufacturing hub, with workshops for making useful items from stone, bone, leather, wood, copper, clay and other raw materials. And it was a seat of government, where people gathered to make democratic decisions on matters such as designation of hunting territories and regulation of harvesting.

Natural resource use was carefully regulated and tariffs were imposed to support the functions of government — while still allowing domestic trade to flourish.

With European contact and demand for furs, trade with Indigenous peoples became the top priority for the French and British. They pushed for “freer,” more globalized trade.

When Samuel de Champlain journeyed upriver to the Algonquin “capital” and met Algonquin leader Tessouat in 1613, his aim was two-fold: secure a military alliance against the British and their Iroquois allies, and proceed further upriver and initiate direct trade relations with other Indigenous peoples in the fur-rich upper Great Lakes area. Tessouat, recognizing the threat to the Algonquins’ control of trade, did not allow this. By way of compensation, he sent Champlain back downriver with a party of 40 canoes laden with furs that could be exchanged for French metal objects such as pots and guns.

Tessouat’s trade protection efforts eventually failed. By the mid-1600s, Algonquin society — and Indigenous trading relations — had largely been destroyed by a combination of factors: ongoing wars (fuelled by firearms) between the French, British and their native allies for control of the beaver trade; Iroquois raids; and introduced diseases such as smallpox and influenza.

Environmental hazards

A hundred years later, after the British defeated the French, harvesting of the Ottawa Valley’s great pines and land clearing for agriculture began in earnest. Game and fur-bearing animals became scarce and huge areas were permanently alienated from traditional Aboriginal use.

European colonization and international trade created a boom-and-bust cycle in natural resources such as fur, timber and fish. After the bust, the Ottawa Valley’s original inhabitants were left impoverished and landless. Many descendants of European colonists living in the area have also seen their incomes shrink, particularly after NAFTA came into force and triggered factory and mill closures.

Furthermore, diseases and pests introduced through international trade have permanently altered the Ottawa Valley landscape. White pine blister rust, Dutch elm disease, and now emerald ash borer have affected tree species of ecological and commercial importance.

Trade negotiators generally have little knowledge about these environmental risks and tend not to address them seriously. A big unknown in the TPP deal has been the fate of British Columbia’s raw log export restrictions. Japan has pressured Canada to lift these restrictions. Not only would this seriously harm B.C.’s forestry industry, it could backfire on Japan if imported raw logs introduce invasive alien pests and diseases to that country.

The latest TPP news suggests that Japanese and Canadian officials will have further talks about exports of B.C. logs, but restrictions can stay in place for the time being. Being a trade lawyer is a great job if you can get it — Japan’s a nice country to visit.

Stephen Harper touts free trade as bringing “wealth and opportunity,” but for whom? The main beneficiaries are a privileged minority, many of them outside Canada. International trade does not generally bring wealth and opportunity for the majority.

Investor-state dispute settlement

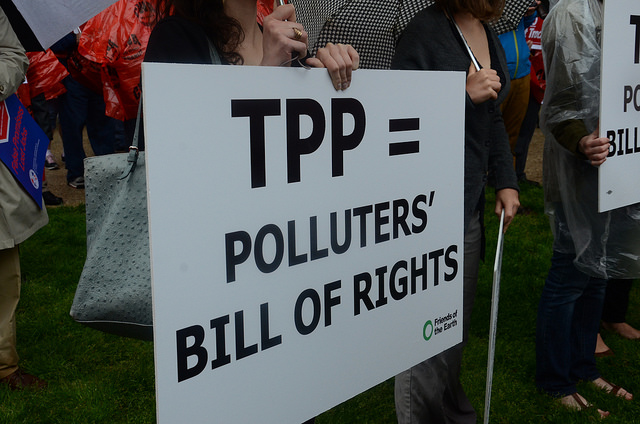

One of the worst environmental aspects of trade deals are investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanisms. Canada’s involvement with ISDS started with the infamous Chapter 11 of NAFTA, has spread to the Canada-EU trade deal, and now the TPP. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives reports that Canada had paid over $172 million to U.S. investors after adverse rulings by trade dispute panels as of the end of 2014, but the U.S. had never lost a NAFTA chapter 11 case. Trade dispute lawyers fear the U.S. will pull out of NAFTA if they rule against the U.S., but don’t care if Canada loses its dispute cases.

The Globe and Mail ran an article in June, asking, “Where is Canada’s national debate over trade dispute panels?” It cites a recent trade dispute panel ruling that overturned a Canadian environmental assessment decision blocking a proposed rock quarry on the Bay of Fundy. The panel ruling opens the door for a Delaware-based company to seek damages of up to $300 million from Canadian taxpayers.

Unlike greater trans-Pacific trade, more domestic trade would directly benefit Canadians. And, in the context of combating climate change, it would not trigger major increases in greenhouse gas emissions. Whether or not the TPP ever becomes a reality, Canadian trade would benefit from renewal of our national transportation infrastructure — particularly a rebuilding of fuel-efficient railways, which recent federal governments have allowed to deteriorate significantly.

History suggests that trade globalization can have major negative aspects. Investments in science, education, technology innovation and domestic transportation infrastructure — plus effective regulation of natural resource use — are a better prescription for national prosperity.

Ole Hendrickson is a retired forest ecologist and a founding member of the Ottawa River Institute, a non-profit charitable organization based in the Ottawa Valley.

Photo: AFGE/flickr

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.