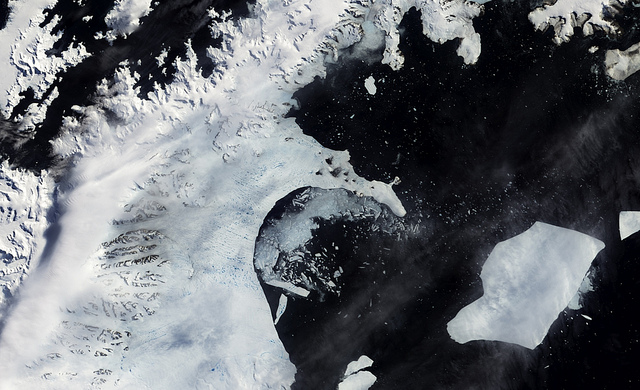

These days the World Wide Web looks a lot like Antarctica’s Larsen B Ice Shelf — a large, open mass disintegrating at the edges because of human interference.

A lot of people make the mistake of thinking that the Internet and the World Wide Web are the same thing. That’s understandable. The World Wide Web made a public splash in the early ’90s when it became possible to create and display text, tiny pictures and even tinier video clips via a web browser on a computer screen. It was an overnight success, 20 years in the making.

The Internet, the underlying public network that made the World Wide Web possible, had been around since the ’60s. That’s when the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA)-funded project allowed a handful of university research computers to send data amongst themselves. And really, that’s all the Internet is, a way of one electronic communications device to share information with one or more devices anywhere there is a connection — wired or wireless — anywhere in the world.

The World Wide Web is just one way of doing that. Its society-changed advantage has been that it has been open, more-or-less democratic and searchable by anyone with a browser, regardless of device or operating system.

Unfortunately, as the web has grown it has been required to take on the burden of transmitting pages that contain large images, video, audio, ads, Flash animations, metric tracking plug-ins and all manner of cruft that slow down the delivery of a site’s key content, especially on mobile devices. Properly designed web pages can alleviate a lot of the sluggishness.

But, many news sites have an accretion of legacy code and ad junk. Publishers seem to be more interested in garnering fleeting revenue from pages rather than working to make them streamlined. That’s one reason why the Facebook Instant Articles deal I’ve written about recently looked so appealing to publishers. Facebook yanks rich media content out of the cruft and displays it at a rate that isn’t hair-pullingly leaden.

Meanwhile mobile device users have discovered that while the web is good at displaying a large body of information, it makes a lot more sense to have factoids and nuggets of information, like stock prices, weather or news alerts delivered via purpose-built apps that make best use of the limited real estate on their smartphones. And, in developing nations, smartphones are the computing device of choice and apps trump web pages, especially when bandwidth is scarce or costly.

And, of course, service-oriented Internet-based services like Uber, Open Table or Airbnb make far more sense as dedicated apps. So do podcast aggregators like Overcast, for example — all of which also have handy versions for the smallest of all mobile screens — the smartwatch.

Finally, there’s the Internet of Things. Lightbulbs, switches for household appliances, smoke detectors, thermostats and even doorbells can now communicate with each other and smart devices via the Internet or other wireless communication protocols like Bluetooth.

That all means that the open, democratic space is at risk as more and more content creators move their information to walled gardens like Facebook or to apps that live only on Android, iOS or Windows devices or between devices that only talk to, and learn from, each other.

That could mean that while public discourse will still happen on the World Wide Web, more and more conversations will take place on the ice floes that have broken from the mainland. Those without the right devices or memberships to listen will be frozen out, left only to stand on shore and wave goodbye.

Listen to an audio version of this column, read by the author, here.

Wayne MacPhail has been a print and online journalist for 25 years, and is a long-time writer for rabble.ca on technology and the Internet.