On April 23, the Fraser Institute released the annual update of their misleading Consumer Tax Index report. The piece is meant to feed the anti-tax sentiment with numbers sprinkled liberally for their shock value instead of providing any meaningful analysis. Here are some of the main flaws with the report’s methodology.

If what follows sounds familiar, it’s because I’m drawing heavily from the analysis I did in 2010 here, here and here. All of these critiques continue to apply to the 2013 report, which is based on the exact same problematic methodology as earlier editions employed.

The Fraser Institute’s report claims that the total tax bill of the average Canadian family now takes up 42.7 per cent of their income and has increased by 1,787 per cent since 1961 (without adjusting for inflation). This are big numbers, but when we look closely at how how they are constructed, it becomes clear that the Fraser Institute doesn’t even come close to measuring the tax bill of what most people would think of as the average or a representative Canadian family.

The Fraser Institute’s definition of the average Canadian tax bill includes all personal and business taxes, import duties and resource royalties (i.e. the rents we charge for natural gas extraction, water use and timber logging) collected by the Canadian government divided by the number of households in the country. This is an easy calculation to make, but unfortunately it not correspond to what individual families actually pay; it is too broad to be meaningful and takes no account of the distribution of income and taxes between business and families or between individual families at different levels of the income ladder.

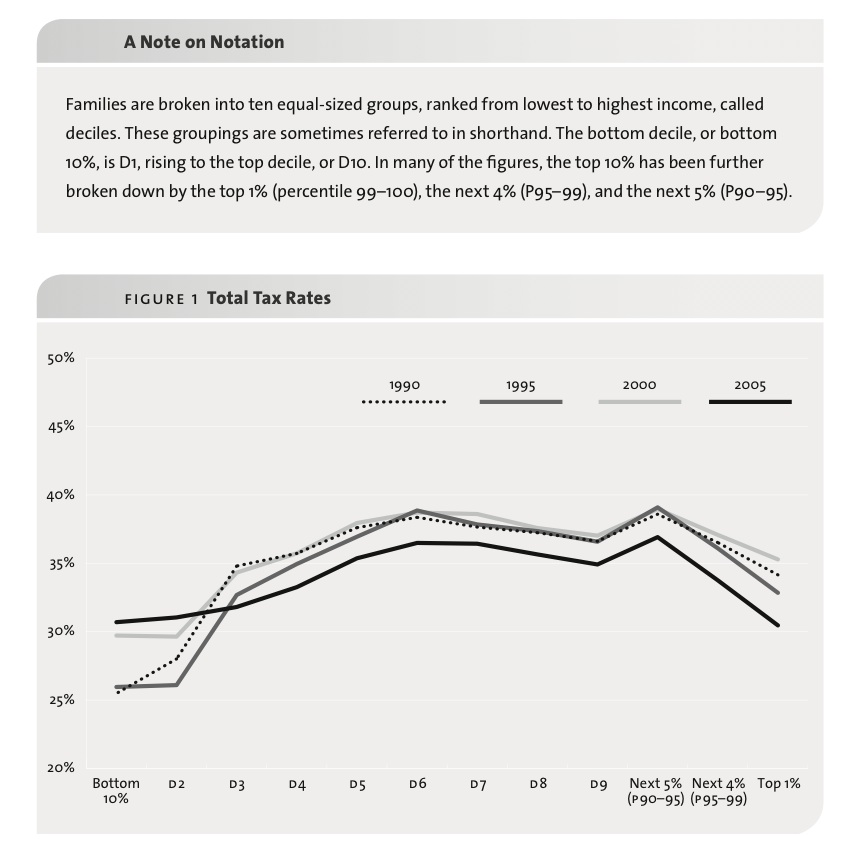

A much better, though considerably more calculation-intensive way to get at the Canadian families’ tax bills looks at the taxes families actually paid, using Statistics Canada’s SPSD/M model. My colleague Marc Lee did this in his 2007 report Eroding Tax Fairness. The figure above shows what he found.

Marc Lee found that the total tax rate for families in the middle of the distribution in 2005 (deciles 4, 5, 6) was around 35 per cent of income, with lower income families paying less and families in the top 1 per cent also paying less as a share of their income, as the figure above shows.

By focusing on the average tax bill per Canadian household (which is different than the ordinary Canadian family’s tax bill), the Fraser Institute report misses out the biggest problem Canada has with its tax system today: the erosion of tax fairness. We’ve seen some fundamental shifts in who pays taxes in this country since the 1990s:

– A shift of the tax bill from business to families (achieved through large reductions of corporate income taxes and a proliferation of business subsidies and tax credits)

– A shift of the tax bill from higher income to middle and modest income families (achieved through personal income tax cuts at the high end and an increased reliance on regressive taxes)

At the same time, overall taxes have actually fallen for all but the lowest-income Canadian families since 2000, as shown in the figure above (and in the Fraser Institute report’s figure 4). Tax revenues have correspondingly fallen as share of our economy, which is why many services all Canadians rely on are now overextended or scaled back. Canadian families feel squeezed because our tax system is unfair, not because we’re collecting too much overall in taxes.

But back to the Fraser Institute’s Consumer Tax Index report. Here are three main issues with the conclusions they draw:

1. The representative/ordinary Canadian family does not pay for the average (or mean) business taxes levied in the country, not does it pay for the average (or mean) personal taxes. With income distributed so unequally and highly concentrated among the top 1 per cent of Canadians, the average tax bill is a meaningless mathematical construct. For example, research shows that most, if not all, of the business tax bill falls on investors (not workers) and given how unequally distributed shareholder profits and investment earnings are these days, the average has become meaningless — it’s artificially pulled up by those with higher incomes and does not represent the experience of most families. Taking the average (mathematical mean) doesn’t make sense when talking about personal income taxes, which are progressive, with rates that increase with income. For example, both main parties running for government in B.C.’s May 14 election have proposed a tax increase on incomes over $150,000. This tax increase will only affect the top 2 per cent of British Columbians, while 98 per cent of us will not see our taxes change. Yet, a future year Fraser Institute Consumer Tax Index report will be showing a small increase in the average family’s tax bill with their current methodology.

Statistics Canada’s latest taxfiler data tells us that individuals in the top 1 per cent paid on average 33 per cent of their income in federal and provincial income taxes while the bottom 90 per cent paid an average of 12 per cent of their income. The Fraser Institute’s report estimates that the average family spent 29.1 per cent of their income on taxes, so you see the problem here.

2. Even if we overlook the distributional issues and accept the Fraser Institute’s numbers, knowing that the average family pays a higher percentage of its income in taxes today than the average family paid in 1961 doesn’t answer the question of whether this is too much or too little. We need to take account of what Canadians get for their taxes to make that kind of judgment. The Fraser Institute report, however, completely misses this part of the equation.

Canada’s made much progress since 1961. We established Medicare (starting in Saskatchewan in 1962) and introduced the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) in 1965, boosted education programs for our children, and modernized our infrastructure to name just a few. These things cost money, so of course taxes have increased.

What’s important to note is that the average Canadian family in 2012 got more out of public programs and services than the average family in 1961. And that if we weren’t pooling our resources together in taxes, we’d still have to pay for healthcare, education, infrastructure and provide support to our elders. The only difference is that we’d have to pay privately, as individuals, and those who can’t afford it would have to go without. For most of us, this would mean a lower quality of life, more insecurity and less money in our pockets, not more.

In addition to providing services, a large chunk of government’s tax revenues flow back to Canadians in the form of direct transfers, such as old-age pensions for our elders, EI payments for the unemployed, and child benefits for parents. The Fraser Institute includes government transfers in their calculation of family income, but you won’t find this out in this edition of the report – you need to look up a 2008 Fraser Institute book that is cited in the report to get at their definition of family income (or family cash income, as they call it). Well, I did, and I found that family cash income includes wages and salaries, but also unincorporated non-farm income, interest, dividends, private and government pension payments, old age pension payments, and other transfers from government.

Without getting into a discussion of what percentage of Canadian families receives income from dividends and other investments, and how meaningful averages are when the distribution is so unequal, let’s just note that old age pension payments and other government transfers account for a large share of the average family’s cash income. In 2007, the latest year for with Fraser Institute numbers are available, they estimated that the average family received $2,125 in old age pension and $8,344 in other government transfers, for a total of $10,469 or 16 per cent of their “cash income” of $66,496.

On average, then, almost half of the family’s total tax bill came back to them in the form of direct transfers from government. The other half was used to pay for services like education, healthcare, policing, justice, road construction and repair that Canadian families used and benefited from. This doesn’t seem like such a bad deal, after all. It’s curious that the Institute decided not to publish this part of their calculation since the 2008 edition of the report.

3. Comparing the average Canadian’s tax bill to the costs of shelter, food and clothing is neither here nor there. With economic and social progress, societies move towards spending less of their incomes on basic survival and having surplus value left over for other pursuits like leisure, better education, better health. It’s not surprising that the cost of basics consume a lower share of Canadian family income in 2012 than in 1961, it would be very worrisome if it didn’t given our economic growth since the 1960s. Comparing the taxes we pay to improve our quality of life through better health care, education, environmental protection and infrastructure development to a number that’s bound to go down over time (expenses of shelter, food and clothing) is a gimmick to make the tax bill appear to be larger and growing faster than it actually is.

The main tax issue facing Canada isn’t that average Canadians are paying too much taxes, but that high income Canadians and profitable businesses are paying too little. For more on that and how to fix it, see this recent CCPA report I co-authored with Marc Lee.