In September the federal government triumphantly announced the conclusion of the Canada-European Union Economic Trade Agreement (CETA). Again. The government boasts that CETA will benefit all Canadians, bringing $12 billion annually to the economy. Generous projections aside, does the government even know how the agreement will affect Canadian men and women? The answer is “no.”

So you might be wondering:

Was gender considered in CETA?

The CETA negotiations were a gender-blind process. The Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development’s (DFATD) annual performance reports in the last four years have not mentioned gender-based analysis (GBA) or gender. So it is not surprising that the development of CETA did not include such considerations. Although DFATD has a consultative process involving a range of stakeholders (which has been internationally criticized), there is no systematic consideration of a gender perspective in trade agreements. This is interesting given that Canada promotes gender equality in development initiatives abroad.

Were women consulted in the process?

No.

Here’s what happened:

- The Standing Committee on International Trade (CIIT) produced two reports on CETA, neither of which mentioned gender.

- There was no discussion in parliament of the effect CETA will have on women or if it will impact women and men differently.

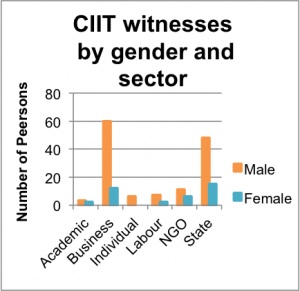

- 19 percent of the 109 witnesses to the CIIT were female. Gender was not mentioned by any witness in their statement to the committee.

These factors prevented gender or women’s issues from being addressed in the CETA negotiations. Even if more women were included in the CIIT or the negotiations, it is unlikely that this would increase representation of gender issues on the trade agenda, unless GBA was also integrated into DFATD’s ex ante assessments of trade agreements.

Why does this matter?

CETA, when combined with cuts to public services and the implementation of regressive policies, will mean that Canada’s gender gap could widen. These changes need to be considered together because CETA will further undermine the public sector. This is important because women rely more on public services, face less employment discrimination in the public sector, and are paid comparatively more in the public sector than in the private sector.

Here’s how:

- Although most industries will see job losses, the few sectors that will see job growth (natural resources and agriculture) are male-dominated. Women’s participation makes up four percent of the sector and has changed little over the last ten years.

- CETA will not reduce the pay gap between men and women because the bulk of job creation will be in the private sector where the wage gap is consistently greater. Natural resources, agriculture and related productions operations (the bulk of CETA’s job creation), have the largest gap between public and private wages: women make on average $11,000 more per year in the public sector in these industries than they do in the private sector.

- CETA will facilitate the liberalization of public services. This will most likely lead to greater deregulation and privatization of health care, education and other social services, such as municipal water provision. Cuts to public services will force women into the private sector where there is less protection, greater risk of discrimination, and comparatively lower pay.

- CETA’s patent rule changes are predicted to increase costs for drugs by $850 million. As women consume more prescription drugs than men, they will pay an additional $110 million per year on prescription drugs.

CETA is a bad deal economically for Canada because it will exacerbate existing inequalities between men and women, reduce access to resources that will disproportionately affect women, and impede economic stability and growth.

This is why the federal government must include a gender perspective in assessments of Canada’s free trade agreements going forward. Effective consultation mechanisms, the implementation of GBA, and monitoring mechanisms will ensure trade is more equitable for all Canadians.

Amy Wood is a research assistant with CCPA’s Making Women Count project, and her research interests include international trade and gender equality.