We’ve known for a long time that we all pay for poverty. We just didn’t know how much.

This is the question I investigate in my latest CCPA report The Cost of Poverty in B.C. If you’re not in the mood for reading the report, you can watch a short video that summarizes the findings here.

Study after study has linked poverty to poorer health, lower literacy, more crime, poor school performance for children, and greater stress. In this report, I use the statistical association between poverty and these negative outcomes documented in the research literature, and combine this information with estimates of the costs these outcomes impose on government finances and on society at large.

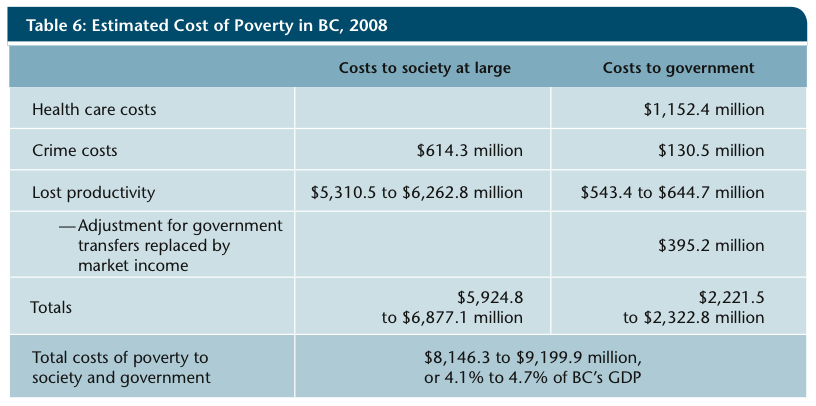

My findings confirm what we’ve already suspected: poverty comes with a very high price tag. The cost of poverty to government alone is estimated to be between $2.2 to $2.3 billion per year. The costs to society as whole is $8.1 to $9.2 billion annually. That’s a lot of money — close to 5 per cent of the total value of our economy.

The study focuses on two types of costs in particular. First, I quantify the societal resources devoted to tackling poverty’s negative consequences. These include the health and crime-related costs of poverty. Second, I capture the economic value of foregone economic activity and lower productivity that are associated with poverty. B.C. isn’t using all the talents and productive potential of its citizens who live in poverty and this acts as a drag on our economy. These costs are what economists call “opportunity costs”: they do not represent resources we’re actually spending now but rather resources that would become available to society if poverty was significantly reduced or eliminated.

The methodology is based on a landmark Ontario study, The Cost of Poverty in Ontario: An Analysis of the Economic Cost of Poverty in Ontario. The Ontario project was a collaboration of a number of prominent business economists and researchers, who developed a systematic way to account for the monetary cost of poverty both in Ontario and in Canada as a whole. The advisory team included then TD Bank Senior Vice President and Chief Economist Don Drummond, Canadian Policy Research Networks Senior Fellow Judith Maxwell, among others.

The break-down of the cost of poverty in B.C. is shown in the table above.

Note that these estimates do not capture all of the costs of poverty. Notably excluded are the costs that child poverty imposes on future generations by perpetuating the cycle of poverty. I also do not measure many of the less tangible costs, such as the impact of high poverty levels on social cohesion and our feelings of safety in our communities. The direct cost of providing frontline social services to those in poverty are also not counted.

Poverty takes an enormous toll on the people who experience it. On this basis alone, we must do better than having one in nine British Columbians in poverty (the highest poverty rate in Canada).

This article was first posted on The Progressive Economics Forum.