There are two reasons why it is difficult to comment on the legacy of a finance minister.

1) It is a tremendously challenging job, anywhere, any time. Stewarding one of the largest economies in the world through a global economic crisis is no cakewalk, and it has clearly taken a toll on Jim Flaherty. (Canada has fallen from 8th to 11th largest economy since 2006.) Critiquing this performance, when so many factors are beyond an individual’s control, and so much soul-searching takes place behind the scenes, is neither easy nor lovely.

2) Where does a prime minister end and a finance minister begin? There is little sunshine between these two positions in any administration, all the more so with the Stephen Harper administration. Nobody is confused about who is boss. So are we judging Mr. Flaherty’s legacy, or Mr. Harper’s?

Still, Mr. Flaherty’s departure is a good time to trace his eight-year contribution to Canada’s fiscal history.

Here is a contrarian view on four widely touted accomplishments, and two major developments that have received little notice in the roundup of opinion on the Flaherty legacy.

Canada’s global performance

So much of what happened under Mr. Flaherty’s watch can be attributed to global phenomena, both good and bad. It’s a big stretch to describe Mr. Flaherty’s hand on the tiller as the reason Canada fared relatively well through the global economic crisis. Canada’s economy was a major beneficiary of double-digit growth in China, which continued to 2010, propelling our resource sectors as manufacturing took a beating. That’s why our economy rebounded so sharply in mid-2009.

Housing sector

Mr. Flaherty was hailed for showing bravery by disciplining mortgage markets four times. But people forget it was none other than his office that gave the green light on zero-down 40-year mortgages in 2006, the ruinous public policy that underlay the housing crisis in the United States and greatly expanded the roles of mortgage insurers such as AIG and Genworth in Canada. As rising household indebtedness — driven primarily by the rush into home ownership — became the No. 1 domestic economic risk, the feds had little choice but to reverse course.

Stimulus

Mr. Flaherty was saluted for showing an open mind and reversing his position on stimulus. Really? It would have been nothing short of fiscally reckless not to do so in January, 2009 (after insisting no deficit would occur, and no action was needed, in November, 2008). Governments around the world were trying to put a floor under a global economic crisis that had no equivalent since the 1930s. No one knew where the bottom would be. Even so, it took the unusual step of proroguing Parliament in the midst of the crisis for the feds to get their act together.

Balanced budgets

Mr. Flaherty is widely praised for fiscal stewardship and balancing budgets. Anyone can balance a budget. How you do it is what’s important.

The more than $220-billion in cumulated tax cuts promised since 2006 stripped the $18-billion budgetary surplus he inherited and undermined the government’s revenue position, making the federal deficit a far deeper hole to climb out of, and had the dubious virtue of adding to corporate cash piles that the former Bank of Canada governor, Mark Carney, called “dead money.”

Not one tax cut was delayed or postponed during the crisis. The “revolutionary” Tax Free Savings Account was actually introduced in the eye of the economic storm, January 2009, a time when what was desperately needed was more spending power, not less. A flurry of boutique tax cuts in subsequent budgets added 383 new tax loopholes.

To balance the books, direct federal program spending was deeply cut (fewer statistics and the end to many archives; massive staff cuts in monitoring tax evasion and fraud at Canada Revenue Agency; less food safety inspection; inadequate rail oversight; the list goes on). These cuts will deliver a surplus by 2015 (or before), just in time for a federal election. This is a political, not fiscal, imperative. It should score no points among those looking for sound public finance decisions.

Income inequality

The costly rush toward a balanced budget will permit the Conservatives to make good on election promises made in 2011, ushering in billions of dollars more in tax cuts (income splitting for families with children anddoubling contribution limits to Tax Free Savings Accounts) that have been shown by the Finance Department itself to provide more benefit to the richthan everyone else.

Income inequality is the one thing you don’t want to make worse. It slows development (says the World Bank), drags economic growth (International Monetary Fund), is the “ultimate social time bomb,” (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) and can lead to undeveloped potential and political instability even in nations such as Canada (Conference Board of Canada). Electoral promises that are known to worsen inequality do not show good fiscal or political judgment, which is perhaps why Mr. Flaherty twitched over the income-splitting proposal at the end of his tenure.

Fiscal federation

Mr. Flaherty has presided over one of the most startling periods of balkanization of our fiscal federation. It’s all the more startling since his home province of Ontario, the nation’s most populous, has been hit hard by almost every unilateral decision: A rejigging of equalization payments in a manner that pits province against province; defining how training dollars should be spent; promising but not spending money for municipal infrastructure and affordable housing; ending the 10-year Health Accord later this month.

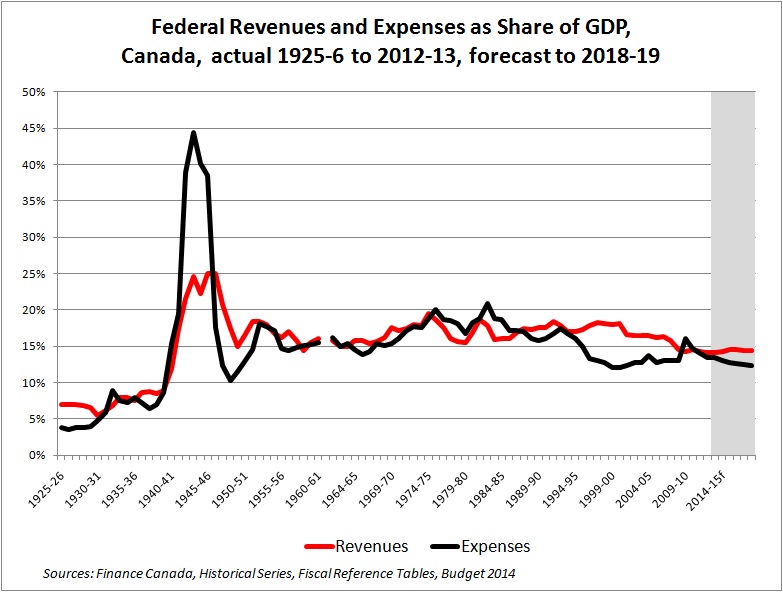

This is also the first recession since the Second World War in which the provinces have done more of the heavy lifting than the feds, and one whose aftermath deliberately steers us to the smallest federal presence in the economy since the late 1940s.

Is this legacy pragmatic? Prudent? Steady-handed? More like ideological, frequently reckless, and just plain lucky.

But even as someone not persuaded by Mr. Flaherty’s policies or politics, I rue the loss of his presence at the cabinet table. The arc of his eight-year tenure as Canada’s Finance Minister began with a certain fiscal swagger, but ends with what appears to be more sombre and thoughtful humility.

That’s exactly what Canada needs today.

This piece was originally published at the Globe and Mail’s online Report on Business feature, EconomyLab.