We continue our special series of commentaries marking the 50th anniversary of the publication of Mel Watkins’ classic article, “A Staple Theory of Economic Growth,” with the following contribution from Daniel Poon. Daniel is one of Canada’s leading experts on the theory and practice of industrial policy, and the successful industrialization experience of East Asia. He is an economic affairs officer with the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), previously worked as a researcher with the North-South Institute (NSI), and was a Fellow with the Walter & Duncan Gordon Foundation. Here he applies lessons from Asia’s experience, and the rise of China in the global economy, to Canada’s continuing industrialization challenge. Can China be more than a market for Canadian staple resources — and more than a source of upward pressure behind the global prices of those staples?

In times of crisis, leading thinkers often reach back to classic texts and writers for core insights to present policy problems, and so it should be with Melville Watkins’ classic 1963 article “A Staple Theory of Economic Growth.” Fifty years on, it is striking how the fundamental tenets of the staple theory, and the risk of getting caught in a “staple trap,” continue to resonate today regarding Canada’s economic outlook. Moreover, a great number of developing countries are also seriously concerned over an economic ‘curse’ or ‘disease’ from resource-dependence.

But it was his subsequent work arguing for strict regulation over foreign direct investment in Canada that was not only fit for its time, but ahead of it, in light of the more recent revival of themes such as ‘resource nationalism,’ ‘state capitalism,’ industrial policy, and ‘covert protectionism’ that have returned to the policy debate. These trends may have yet to fully filter through to Ottawa, but when they do, heterodox economic approaches may have an opening to press for an overhaul of what Watkins called the “(staple) export mentality” that inhibits more diversified Canadian domestic development (p.150).

The ongoing relevance of the staple theory may not be all that surprising in an era, perhaps now passing, of an international commodities price boom that further concentrated economic production in natural resource sectors in many countries (Haglund 2011). But Watkins’ contribution also plays a part in a larger discussion connected to the 2008-2009 global financial crisis — one that forced policy-makers the world over to re-think the conventional wisdom that placed primacy on unfettered market forces over the ability of government instruments and institutions to achieve public policy objectives.

The pendulum between state and market is rebalancing towards the former, albeit not as quickly as many progressive groups would like. One of the underlying sources of the policy re-think has been the rapid emergence of China as a pre-eminent power in the world economy. This historic change has had many implications (including, obviously, an impact on global commodity prices), but it has also demonstrated the power of a state-directed strategy for industrialization and diversification, with lessons for Canada’s own efforts to grapple with the staples challenge.

China is more than just a market for our staples, and Canadian policy-thinkers would do well to imagine a more active, strategic partnership with China so as to better understand its ambitions to deepen its industrial base and reach the apex of global production chains.

Kicking off a re-think

One convenient marker for the fundamental re-think in development and industrial policy-making occurred in March 2011 at an International Monetary Fund (IMF) conference that sought to distill the policy lessons from the crisis. Among the leading policy-makers and academics in attendance, it was a presentation by former Harvard professor Dani Rodrik that set the direction and tone for subsequent re-thinking of growth strategies in the aftermath of financial crisis, particularly for developing and emerging countries.

In this presentation, Rodrik drew on insights first developed by W. Arthur Lewis’ work on dual economies that equated economic development with “structural change.” The core idea was that countries attain prosperity by diversifying away from agriculture and other traditional products, towards modern economic activities, and as this change is underway, overall productivity is bolstered and incomes expand. Lewis typically stressed the large differences in productivity between broad sectors of the economy — between traditional (rural) and modern (urban) sectors — and noted that this difference between sectors could be an important engine of growth even if productivity growth within individual economic sectors was minimal.

In the paper, Rodrik (with Margaret McMillan) identifies this “growth-enhancing structural change” as an important contributor to overall growth performance. Crucially, he contends that the bulk of the difference in recent growth experiences in Asian countries versus those in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa can be understood by the discrepancies in the contribution of structural change to overall labour productivity. Thus, while in Asia high-productivity employment opportunities expanded and structural change added to overall growth, the opposite has been true in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa where labour has moved from more-productive to less-productive activities (most notably, the informal sector), and structural change has served to reduce rather than increase growth since 1990 (McMillan and Rodrik 2011).

The key to getting the good kind of structural change, it seems, has been Asia’s strategic approach to economic liberalization that pragmatically combined promoting new, export-oriented economic activities, while simultaneously supporting other activities that directly compete with imports. Latin American and Sub-Saharan African countries, meanwhile, had generally pushed through reforms dictated by the so-called Washington Consensus. The wider point, though, is that since that presentation in March 2011, the global policy community has adopted Rodrik’s re-working of Lewis’ “structural change” concepts hook, line, and sinker.

Now, the concept of “structural change/transformation” has been accepted almost to saturation in economic development circles. This is particularly the case (but not only) with multilateral institutions which all recently published major reports on the issue, such as the World Bank, the African and Asian development banks, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER), the Brookings Institution, and the Initiative for Policy Dialogue, to name a few.

Other major institutional about-faces have occurred, too. The IMF, once an ardent proponent of financial liberalization, also recently adopted a new “institutional view” and is now more accepting of government regulation on capital flows (Gallagher and Ocampo 2013). Moreover, its Back to Basics website tries to strike a progressive balance over a wide range of economic issues.

Re-thinking development economics

Watkins, for his part, is clear to present the staple theory not as a general theory of economic growth (or even export-oriented growth), but as one that is applicable to the “atypical case of the new country,” which bestowed on Canada two distinctive characteristics when it began its economic growth processes: a favourable population/land ratio and an absence of inhibiting traditions (p.143).

Although Watkins deliberately sets Canada’s economic history aside as a unique case (as well as that of the United States and the other British dominions), his careful analysis of the determinants of the range of domestic investment opportunities associated with the export of a given staple — or the linkage between the staple theory and a theory of capital formation — is the core insight of his work that broadens the applicability of the staple theory to other contexts. To this day, the idea that, “economic development will be a process of diversification around an export base,” (p.144) goes to the heart of many developing countries’ core policy objectives.

In the years since, Watkins’ breakdown of the “spread effects” of the export staple sector and the impacts of these activities on the domestic economy and society have been further elaborated. The core model was often restated to the extent that aspects of this analysis, such as the discussion of linkage effects (backward, forward, and final demand), have become ‘old-school’ concepts in the mainstream economic development discourse that has been increasingly fixated on foreign direct investment and insertion into global production chains as the surest route to prosperity.

What is changing now are signs that the “inhibiting export mentality” related to staples/commodities production has been weakened — in tandem with the onset of the global financial crisis that discredited the Washington Consensus policy approach and its excessive emphasis on market forces and static comparative advantage. In his paper, Watkins remarked that while interest among Canadians in the staple theory had declined, interest among those outside of Canada had actually increased (p.142-3). In surveying current-day responses to the staple trap (or other structural constraints), it so happens that while Canadian policy-makers seem unperturbed by even the possibility of a trap, some policy-makers outside Canada are increasingly taking action to counteract its dislocating effects on their own economies.

A bevy of protection

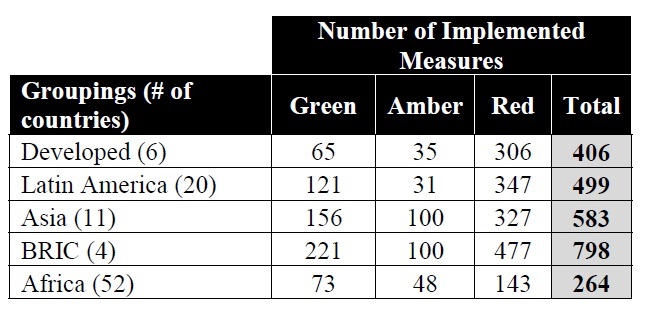

The revival of terms like ‘resource nationalism,’ ‘state capitalism,’ etc. in the mainstream policy lexicon, has led some to believe that “industrial policy in the leading economies of the South is likely to become more significant” (Gereffi 2013:21). Table 1 provides a broad overview (from Global Trade Alert, GTA) of the post-crisis policy responses, regarding the implementation of so-called “protectionist measures” and their breakdown according to degrees of discrimination against foreign commercial interests. ‘Green’ measures are not discriminating, ‘amber’ measures are possibly discriminating, and ‘red’ measures are certainly discriminating (Evenett 2012).

Although there are limitations to the accuracy of the GTA database — its methodology does not account for protectionist measures that may have been already in place prior to its reporting period in November 2008, nor does it have any way of assessing coherence of measures, or quality of implementation — it nonetheless offers a rough snapshot of ongoing global economic trends in government intervention and industrial policy. As shown in Table 1, the four BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China) lead the way in terms of most total protectionist measures at 798 — nearly twice the total of six developed countries (which registered 406 such measures). Other regional groupings in Asia and Latin America also had higher levels of total protectionist measures at 583 and 499, respectively, although these groupings include a larger number of countries. African countries combined for a total 264 measures.

The pattern is roughly replicated when looking at ‘red’ measures only, with the BRIC countries leading the way with 477 measures, followed by Latin America (347), Asia (327), developed countries (306), and Africa (143). During this period, Canada had a total of 52 implemented protectionist measures, of which 29 were deemed of the ‘red’ variety, among the lowest of any within the developed country grouping.

Table 1. Protectionist Measures, Selected Country Groupings, Nov. 2008- Jun. 2013

Source: Global Trade Alert (GTA). See: http://www.globaltradealert.org/

To give a more concrete example, let’s take the case of Mongolia. Following an attempt by the Aluminum Corp. of China (Chinalco) to invest in a coking coal mine in the Gobi desert, the Mongolian government enacted a new foreign investment law in May 2012. The law restricted foreign ownership in businesses worth more than $76 million in “strategic sectors” such as natural resources, transport, food, real estate, communications and agriculture, and requires government approval for acquisitions of 33 per cent or more of a company’s shareholdings, and parliamentary approval for bids of at least 49 per cent.

A year on, with commodity prices weakened and Chinalco having abandoned its bid, Mongolian authorities have adjusted their tack and lowered barriers for foreign investors. But the legislation still allows for more scrutiny in deals with state entities, in light of concerns about economic domination by its neighbour and largest customer. The point is that even small countries now see fit to experiment with the cut and thrust of industrial policies, even if that means challenging a big neighbour. In times past, this may not have been the case. Back in the 1990s, being an eager pupil of the Washington Consensus, Mongolia agreed to rescind an export tax on unprocessed wool in exchange for a loan from the Asian Development Bank. Mongolian authorities are not likely to forget this experience, as these wool exports would eventually be processed in China (Wade 2010).

Of dogs barking and biting

So what explains the seeming reticence by Canadian policy-makers to use similar industrial policy interventions — whether to stem a crisis, or to counteract a staple trap and its associated inhibiting export mindset? Part of the answer, I believe, is due to a chorus of commentators that have constructed a persuasive counter-narrative: namely, that despite enduring the biggest trade shock due to the global financial crisis, the world economy was nonetheless able to avoid a protectionist backlash (unlike the experience of the 1930s in the wake of the Great Depression).

Generally, five explanations have been posited. First, the WTO and other trade pacts have institutionalized liberal trade. Second, countries’ use of monetary and fiscal policies has not been without problems, but has been better than in the 1930s. Third, integration created by global production chains has rendered protectionism self-defeating (i.e. global capitalism has replaced national capitalism). Fourth, social safety nets were in place to cushion people from recession and joblessness. Fifth, the ideology of markets and globalization remains dominant. In short, the sound bite (with some variation) is that “the protectionist dog did not bark” (Subramanian and Kessler 2013; Wolf 2013; Hancock 2013; Wolfe 2011).

Conveniently overlooked is the fact that what the WTO identifies as a protectionist measure is narrower than the definition used by GTA. Thus, some measures recorded in the GTA database, such as investment protection, bailout programs, currency devaluation, and anti-trust measures (among others), would not be considered protectionist measures by the WTO — simply because WTO agreements have limited or no jurisdiction in these areas.

Even the head of GTA, Simon Evenett, put it this way: “While it is not the case that governments have sought flagrantly to flout WTO rules often during the global economic crisis, more and more evidence suggests that they have exploited the incomplete nature of the WTO rules and circumvented them. Such findings leave a rather hollow ring to claims that WTO rules have prevented protectionism during the crisis” (Evenett et al. 2012:287).

Thus, the “protectionist dog” chorus seems content to paint protectionist measures of all stripes as not only more or less the same, but also as all bad. This rather old-fashioned view assumes that protection is absolutely incompatible with boosting trade and growth. This may hold true for North Korea, but you only need a glance at China these days, combining ongoing but selective protections with targeted degrees of openness to trade flows, to start wondering if the assumption is seriously mistaken.

Of course, not everyone has bought into the “protectionist dog” argument. In 2012, the Chairman and President of the U.S. Export-Import Bank, alluded to this very issue: “Believe me, China and other countries will not be shy about using any tool — as much as they can and for as long as they can… State-owned enterprises, sovereign wealth funds, state-directed capital — they will leverage every single one in an attempt to outcompete us” (Hochberg 2012:9).

Others have argued that “the relevance and pertinence of industrial policies are acknowledged by mainstream economists and political leaders from all sides of the ideological spectrum” (Stiglitz et al. 2013:2). For example, these authors point to the EU Commission’s return to using selective interventionist policies, and note that “an entire department at the EU Commission is devoting much financial and human resources to design and help implement industrial policies across the Eurozone” (Stiglitz et al. 2013:3).

Here, Watkins’ Task Force work remains highly relevant and was certainly ahead of its time; some of the strategic tools it proposed, such as investment review and development banks/corporations, remain powerful WTO-legal policy instruments to this day.

A China choice

While the return of ‘state capitalism’ and protectionist leanings are still dismissed in mainstream circles in Ottawa, these trends are increasingly rooted in emerging countries, among which China retains an obvious leading role. Canada is not likely to remain immune from these trends indefinitely — and to some extent, the federal government has already had its brush up with them, whether in the form of the investment screening of the 2012 CNOOC-Nexen merger, or the blocking of foreign takeovers of Potash Corp. and MDA Corp.

At some point, Canadian leaders will have to choose between either learning from China’s development strategy (and actively managing the opportunities and risks it poses), or trying to tear down the ‘China model’ so that it poses less of a competitive threat to the current global political and economic status quo. Many moves by Canadian policy-makers seem oriented to the second option, but the first option has not been written-off. Efforts such as the “Canada-China Economic Complementarities Study” are welcome, but should only be a first step. The next step should be a more strategic exercise that takes dynamic rather than static comparative advantage at its heart (Poon 2012a; 2012b; 2012c). This is where heterodox economic discourse should play a key role.

As has been noted, Canada “has a profusion of industrial policies, what it lacks is a strategy” (Ciuriak and Curtis 2013:1). Perhaps a way out is to recognize that, in the past, Canada appeared adept at ensuring that so-called clandestine U.S. industrial policy (Block 2008) could also benefit Canada. What’s to stop Canada from doing likewise (but hopefully better) vis-à-vis China’s (less) clandestine industrial policy?

Progressive Canadian analysts not only need to come to terms with China’s rise, but given the changing geo-political winds, to find strategic openings to leverage China’s industrial ambitions in pursuit of Canada’s own public policy goals on a scale that could not be seriously considered before (renewable energy, for example). After all, China seems well aware that “a crisis is a terrible thing to waste” (Rosenthal 2009), and that political-economic dynamic may be the modern day salve for Canada to help shake-off its inhibiting staple export mentality.

A list of references cited in this article is available here.