Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

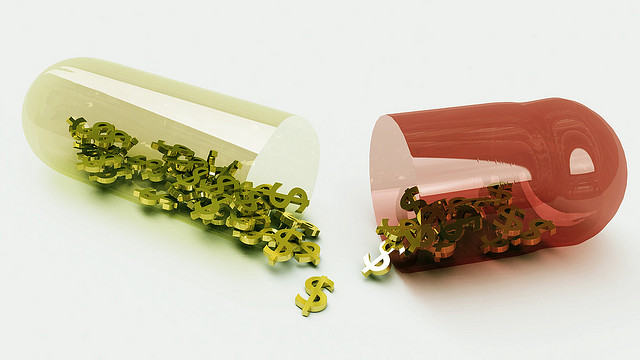

Last week WikiLeaks posted the final text of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) intellectual property chapter hammered out at the TPP ministerial meeting in Atlanta. While the chapter is not as bad as previous leaked drafts, and falls short of the most extreme demands from the brand-name drug industry and U.S. government, it’s still a harmful agreement that will increase drug costs and reduce access to medicines, especially in developing countries. It also has worrying implications for Canada, binding our country to a regulatory regime that would lock in high drug costs.

Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders (MSF) and others have decried the potential impact of the TPP on drug costs and the availability of generic medicines in developing countries. The hardships that will be inflicted on the poor, the sick and the already strained public coffers in developing countries such as Vietnam and Malaysia are reason enough to oppose the TPP’s “abusive” intellectual property (IP) provisions.

What’s more, by establishing a new high-water mark for corporate-friendly IP protections, the treaty sets a terrible precedent for future agreements. MSF concludes that, “although the text has improved over the initial demands, the TPP will still go down in history as the worst trade agreement for access to medicines in developing countries.”

Issues for Canada

What about the potential impacts on regulations and drug costs here in Canada? The official line, according to the government’s technical summary of the TPP, is that its rules “reflect Canada’s existing regime, system and laws” governing intellectual property protection for drugs. Even with the IP chapter in the public domain, it is difficult to verify these assurances until the full TPP text is released and examined by independent experts.

It’s also critical to understand that when government refers to the TPP requiring no changes to Canada’s “existing regime,” it is already including the future changes Canada must make to comply with the Canadian-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), an agreement that has not yet been ratified, let alone implemented.

A quick analysis of the leaked text shows there are good reasons to be concerned that the TPP’s generous IP protections could still prove a minefield for efforts to control drug costs in Canada, already the second highest per capita in the world after the U.S. Here are five problem areas for Canada.

1. Longer data protections for new drugs

Most media attention has focused on the length of data protection for biologics (large-molecule drugs). The U.S. had been pressing others to adopt its standard of 12 years of data protection. Thankfully, the TPP fell short of this outrageous demand, establishing a complicated set of rules that provide from five to eight years of data protection. This is still the longest term of data protection ever enshrined by treaty, and will unquestionably hurt developing countries. Predictably, the insatiable Big Pharma lobby and its Congressional supporters are unhappy.

Canada was cast as a bystander on this issue, because eight years of data protection is in line with our current term of data protection for both chemical and biologic drugs (eight years, plus six months for clinical trials involving children). NAFTA requires only five years of protection for new chemical entities. The TPP, along with CETA, would bind Canada to a higher, more restrictive standard, and lock in our costly, industry-friendly data protection rules forever.

Is Canada otherwise off the hook on the TPP and drug costs? Hardly.

2. A locked-in patent linkage system

The TPP is the first of Canada’s international trade agreements to require “patent linkage.” Under Canada’s existing patent linkage system, before Health Canada can grant marketing approval to a generic version of a brand-name drug, the generic company must demonstrate that all relevant patents on the brand name product have expired. This provides a ready-made pretext for litigation even on spurious grounds, delaying cheaper generic drugs from reaching the market.

The TPP IP chapter does not appear to require any changes to Canada’s current patent linkage system. But none of Canada’s other trade treaties, including the WTO TRIPS and NAFTA, require patent linkage at all, leaving future governments completely free to reform or even eliminate it. Nor would CETA require patent linkage. In fact, patent linkage is not permitted in the EU, where its negative impact on drug costs is well understood. By contrast, the TPP, alone of all FTAs, will bind Canada’s costly patent linkage system, making future cost-saving reforms far more difficult.

3. More generous patent term extensions

The TPP also includes obligations for patent term “adjustments” (a.k.a. patent term extensions), supposedly to compensate patent holders for delays in getting regulatory approval. Experts analyzing similar provisions in CETA conservatively estimate the increased drug costs to Canadians at $850 million annually, which is almost double the savings from removing tariffs on all European goods entering Canada. The TPP and CETA will add up to an extra two years of monopoly patent protection on top of Canada’s existing term of 20 years. By entrenching patent term extensions in two major international treaties, the brand-name industry has won added insurance that these extremely costly concessions can’t be undone by future Canadian governments.

4. New investor rights for foreign drug companies

Another controversial aspect of the TPP is its investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism, which empowers foreign investors to bypass domestic courts and seek compensation before private tribunals when government measures taken to protect its citizens interfere with their investments. ISDS supplies yet another powerful tool for brand-name pharmaceutical companies to protect their monopoly profits, in violation of the espoused principles of free trade.

Under NAFTA’s similar mechanism, Canada is currently being sued for US$500 million by the giant American multinational drug company, Eli Lilly, because Canadian courts invalidated extended patents on two of the company’s drugs. The courts ruled that the patent extensions were not justified because Eli Lilly had failed to provide evidence of new therapeutic benefits. This opened the drugs to generic competition, reducing costs to Canadian consumers and the public health care system. By expanding new investor-state rights to drug companies from Japan and elsewhere, the TPP can be expected to multiply these types of aggressive investor-state challenges against Canada and other countries.

5. Still-secret transparency annex

A final aspect of the TPP that raises concern is its still secret “transparency annex” on health care. Throughout the TPP talks, the U.S. and Big Pharma have been targeting New Zealand’s government agency Pharmac, which does an exemplary job of controlling drug costs by negotiating with both brand-name and generic companies over the costs of drugs that it approves for use in the country’s health-care system. New Zealand’s per capita drug costs are among the lowest in the OECD. In the TPP’s transparency annex the U.S. pursued new rights for brand-name companies to contest the decisions of public drug agencies and tilt the playing field towards “market-based” pricing, increasing costs to governments and the health care system.

New Zealand strongly resisted this push, with little help from Canada. It’s unclear what the final TPP text says, but there are concerns that Canada bowed to U.S. pressure to cover federal drug purchasers under the annex. While most drugs in the Canadian public health-care system are purchased by provincial governments (which will not be covered), the federal government buys for Aboriginal peoples, the military and others. Encumbering the federal government in its ability to get the best therapeutic value for taxpayer’s money when it purchases medicines sets a terrible precedent. It could also interfere with Ottawa’s ability to cooperate with provincial governments in lowering costs and impede the future creation of a cost-effective national Pharmacare program.

‘Not as bad’ is still not good enough

The leaked TPP intellectual property chapter reveals that resistance from other TPP governments, pressure from the generic industry and protest by outside public interest groups successfully watered down the most extreme demands of the U.S. and Big Pharma. While not as bad as feared, this chapter is still very bad, and a set-back for efforts to ensure affordable access to medicines in the Asia Pacific region and beyond. Its worst impacts will be felt by the poorest and most vulnerable in developing countries, but it also has worrying implications for Canada, locking our country into an industry-friendly regulatory regime that virtually ensures higher drug costs for the foreseeable future.

Scott Sinclair is the director of the CCPA’s Trade and Investment Research Project.

The author wishes to thank Gary Schneider and Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood for editorial and research assistance.

Image: Bill Brooks/flickr

Chip in to keep stories like these coming.