My mother says that when she graduated from high school in 1972, she had two occupational choices: nurse or teacher. Nurse and teacher are still the most popular choices for women entering the workforce. Statistics Canada said that more than 20 per cent of all female university graduates in 2011 were teachers or nurses, unchanged from 1991.

Ontario’s Equal Pay Day got me thinking about women’s work, and the systemic reasons behind the stubborn pay gap. Aside from outright discrimination, occupational segregation and unpaid care demands contribute significantly to women’s lower wages.

Evan Soltas had an interesting piece for the American Equal Pay Day, where he points out that women’s share of male-dominated fields has actually been declining in recent years.

For example, women made up 32 per cent of manufacturing workers in the U.S. in 1990 — that’s fallen to 27 per cent now.

That step backwards has been slightly larger in Canada. In 1990 30 per cent of manufacturing workers were women, by 2013 that had fallen to 24 per cent.

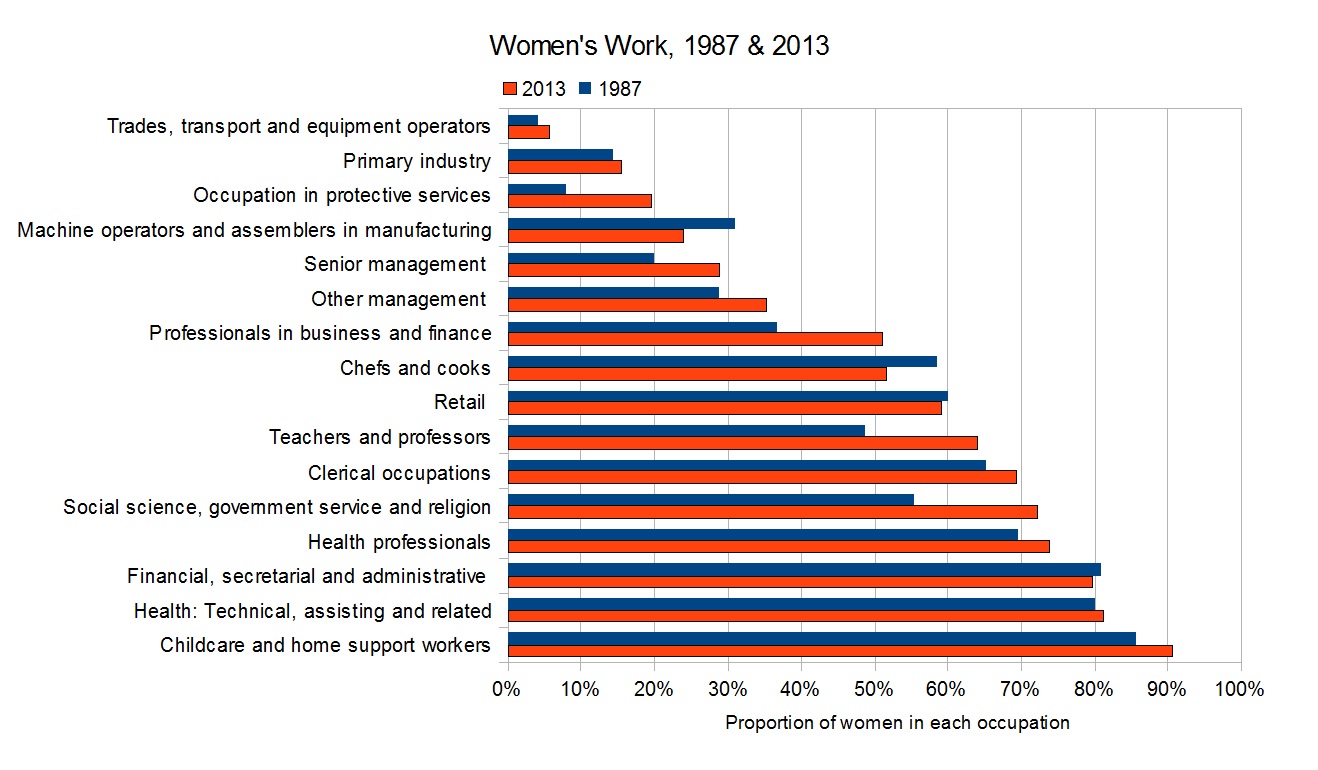

And it’s not just that there are fewer women in male-dominated fields. There are also fewer men in fields traditionally considered “women’s work.” Occupations such as child care, teaching, and health are all now even more female-dominated than they were in the late 1980s.

The chart above compares the proportion of women in selected occupations in 1987 and 2013. There is some good news, such as more women in business and finance professions. But considering that the proportion of young women with a university degree more than doubled over the same period, it hardly looks like much progress has been made.

The other big issue for women is the toll of unpaid caregiving. Often a vicious cycle, where the lower earner takes time off paid work to take care of family members, and ends up getting more of a wage penalty as a result.

Who stays at home to care for family members rather than work, and how do we know? Well, the Labour Force Survey asks why people work part-time, and tells us that in 2013 nearly 400,000 workers chose to work part time to accommodate family caregiving duties. More than 90 per cent of these workers were women. An additional 75,000 workers wanted a job, but weren’t looking because of immediate family caregiving responsibilities. And again, 90 per cent of these workers were women.

Compare this to 1997, the farthest back we can get this data, and there isn’t much change. In 1997, 94 per cent of workers scaling back on paid work because of unpaid work were women — in 2013 it was 91 per cent.

This is why affordable child-care and senior’s home care are such huge issues for core age women. Women pay the price for undertaking essential reproductive economic activities, that I think we can all agree make our society better off.

Occupational choice, unpaid work, discrimination, and societal expectations interact to entrench that wage gap. In some areas, it’s actually getting worse. We need #EqualPayDay, and reports like this from the CCPA to remind us that the wage gap isn’t going away on its own.