Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

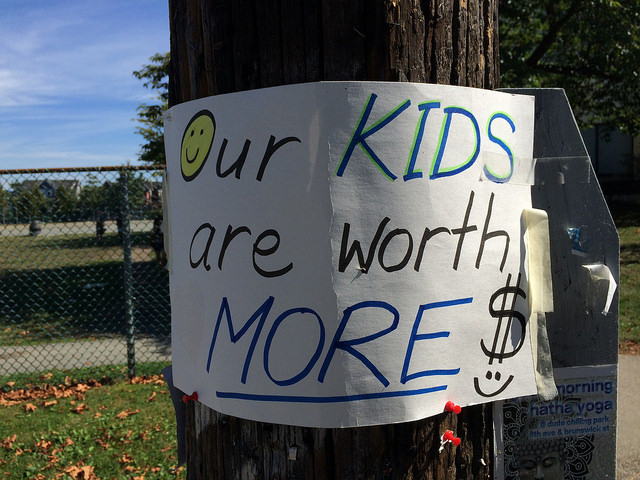

It’s been a year since the longest strike in the history of B.C.’s public school system. A key outcome of that dispute was increased understanding of the phrase “class size and composition.” During the strike, the public came to appreciate that teachers were fighting not just for better wages, but for improved teaching and learning conditions.

The strike gave teachers an opportunity to explain how classroom conditions had deteriorated since the B.C. government gutted their contract in 2002 — removing the limits on class sizes and the number of special needs students per class, while at the same time cutting funding for special education teachers and assistants. Not only had class sizes increased, they argued, but the make-up of those classes had changed quite dramatically. In many different ways, teachers throughout the province asserted that these cuts meant that many more kids were failing to have their unique needs met.

The strike also resulted in the creation of a $75-million “Education Fund” with the primary aim of hiring teachers to address these issues.

A year has come and gone since then. What has happened in that time?

Drawing on the government’s latest statistics, the BC Teacher’s Federation reports that there were 16,156 classes with four or more children with special needs in 2014/15, representing about one in four classes in the public K-12 system. (Special needs designation means students have a recognized disability and are entitled to an Individual Education Plan.) Those numbers were essentially unchanged from the previous school year — itself the worst year on record. In addition, the BCTF reported that there was a “staggering” total of 3,895 classes with seven or more children with special needs this past year. Again, the number was essentially no different than the previous year.

Those numbers are a lot worse than they were even a few years ago. In 2006/07, there were 9,559 classes with four or more special needs students. And prior to the contract-stripping in 2002, many school districts (including Vancouver) had contracts that essentially limited the number of children with special needs in any given class to two.

So what happened to that $75-million Education Fund? The BCTF asserts the money only back-filled already planned cuts, effectively allowing school districts to re-hire about 400 teachers they would otherwise have been forced to lay-off. In effect, the Education Fund has only prevented more cuts, an underwhelming outcome to say the least.

On a related front, it’s been three years since the Moore family won an historic victory for students with learning disabilities in the Supreme Court of Canada. The court found that the North Vancouver School District had failed to provide adequate support for the Moore’s son Jeff, who wrestles with dyslexia. They ordered the district to repay the family for the costs of the private school they had turned to in the absence of adequate support in the public system. The court’s unanimous ruling stated, “Adequate special education is not a dispensable luxury. For those with severe learning disabilities, it is the ramp that provides access to the statutory commitment to education made to all children in British Columbia.”

Yet a recent report from the BC Parents of Special Needs Children asserts that, “many children with special needs are [still being] prevented from exercising their human right to equitably access an education in public schools.” Their report highlights the strain: “Families should not have to choose between paying their bills and the deteriorating mental and emotional health of their child.”

The situation facing children with learning disabilities (LD), the largest subset of special needs, is instructive. The vast majority of these children are integrated into regular classrooms, yet many teachers will freely admit that they struggle to provide the intensive, individualized instruction these kids often require. The government eliminated targeted funding for this group in 2002. As a result, there are now only a handful of specialized programs and services for kids with LD in the B.C. public school system, serving only a small fraction of the thousands of children in this category. And hundreds of kids languish on waitlists to be formally assessed. As it was for the Moores, many families of children with severe LD continue to be driven to seek out supports in the private sector.

The irony in all this is that our collective failure to invest adequately in kids with LD represents a classic false economy: the money we are “saving” on their education now will frequently be dwarfed by the costs necessary to provide for them as adults. For example, the failure to adequately address learning disabilities destines many of these children to underperform throughout school. A 2011 Ministry of Education brief states that “20% of students do not complete high school within 6 years of entering grade 8” and that a further “20% of those who complete are functionally illiterate” (emphasis added). It is likely that many of the children included in these tragic statistics have unaddressed learning disabilities.

Moreover, people with learning disabilities are highly over-represented in the criminal justice system. According to a report by The Roeher Institute (a public policy research institute that focuses on disability issues) people with learning disabilities represent 5-10 per cent of the general population, but 25 per cent of the prison population.

All of this means huge societal costs and missed opportunities, including the reduced economic activity and lower tax revenues of people whose very real potential to contribute will never be realized.

In short, we (and our governments) are paying through the nose for our systemic failure to truly address the issues of class size and composition, to properly fund extra supports for kids with special needs, and in so doing, to honour their human rights. Many hoped that events such as the 2012 Moore victory and the 2014 strike settlement might be the beginning of a turn-around on that front. So far, that promise remains unfulfilled.

Seth Klein is the B.C. Director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Tyson Schoeber teaches at THRIVE, an award-winning public school alternate program for students with learning disabilities at Nootka Elementary in Vancouver.

Photo by Neal Jennings on Flickr

Chip in to keep stories like these coming.