The University of Toronto recently announced it will require students, faculty and staff to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 in order to be present on campus, joining Western University, the University of Ottawa, and others in making vaccination mandatory, and paving the road for more universities to do so.

This requirement only reproduces and further exacerbates already exclusionary divisions in society. Most of the unvaccinated are in the lower economic classes; the poor and the working poor. For example, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than half of unvaccinated Americans live in households that make less than $50,000 annually.

In Canada, strong anti-vaxxers represent only between two per cent to 10 per cent of the unvaccinated population. Close to 60 per cent of the general population is fully vaccinated and 71 per cent have already received two doses of a COVID vaccine; this latest number jumps to 81 per cent when counting only those aged 12 and older. Adding in the anti-vaxxer figures, and assuming that those who have received only the first dose will most likely go for the second, leaves about 10 per cent to 18 per cent of the population unaccounted for.

These are the unvaccinated, and they are not necessarily anti-vaxxers. As public opinion has been quick to point out, many of them live on the margins. They might not have a car, might not have access to childcare, or might face language and technological barriers. Many might also be living in survival mode, and getting vaccinated is at the bottom of their list of priorities.

Curtailing rights for the marginalized, such as the right to education, further marginalizes them, in a context where education is considered the greatest social equalizer. Curtailing certain rights now also opens the door to infringing on them in the future. Consider for example the possibility of access to public housing being restricted to those who are vaccinated.

Some marginalized groups are also less trusting of government and public institutions, especially because they have been feeling the effects of many disadvantageous policies originating from them. Distrust has also been identified as a key factor in vaccine hesitancy. How ethical is it to deny rights to such groups, when this will further marginalize them?

Canada, a major hoarder of vaccines

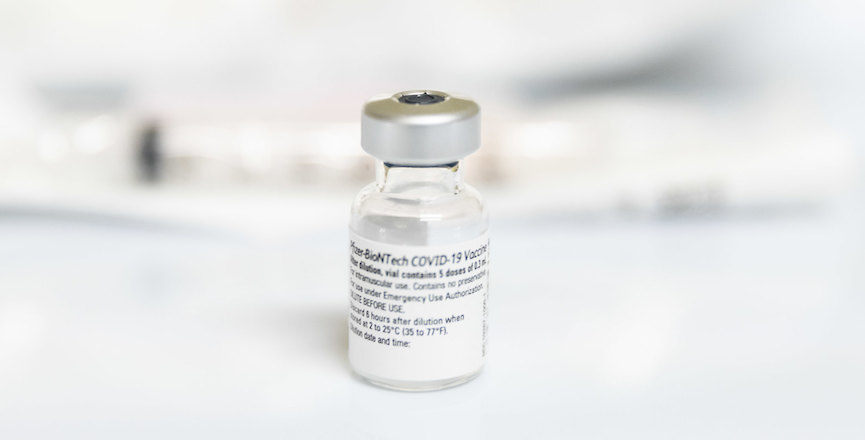

Canada ordered ten times the doses it needed to fully immunize its population. Since December 2020, Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) has signed supplier agreements for 180 million double doses of the various vaccines already authorized by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC); that is, Moderna, Pfizer-Biontech, AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson. If we also count the vaccines awaiting PHAC authorization, such as Medicago, Novavax and Sanofi & GlaxoSmithKline, PSPC’s agreements go up to 400 million doses. These figures are disproportionately high, considering that Canada has a population of just 37 million.

In fact, more than 75 per cent of the COVID-19 vaccine doses have been used by a small group of rich countries: the U.S., the U.K., Canada, Switzerland and the EU Member States. The vaccine race is rich versus poor, Global North versus Global South. In Somalia, Papua New Guinea, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Mozambique, Iraq and Afghanistan, less than two per cent of the population has received even one dose. In Haiti, Congo, Syria, Mali and Yemen it is less than one per cent.

Canada, a G7 country and one of world’s largest advanced economies, dipped its fingers into COVAX, a vaccine-sharing initiative set up to assist in the equitable distribution of vaccines to some of the poorer, developing countries. Venezuela, by contrast, has been shut out of COVAX due to ongoing U.S. sanctions and was unable to collect its vaccine shipments.

In a global context where access to vaccination is unequal and solely the privilege of the rich, how equitable is it to make vaccination requirements mandatory, especially in the case of educational powerhouses like the University of Toronto, an institution that positions itself as a global actor with 21 per cent of its student body coming from abroad?

Are Western vaccines the only acceptable choice?

Added to the issue is also the fact that Canada recognizes only Western vaccines. How should educational institutions handle foreign students who have received two doses of the Sputnik vaccine, for example? In Syria, Sputnik is the only approved vaccine.

Let us say that educational institutions set up clinics for students to get vaccinated. The University of Toronto for example has vowed to provide space and volunteers for vaccine clinics on its three campuses in partnership with local hospitals. How will such educational institutions treat students who have already been vaccinated abroad but with vaccines unrecognized in Canada? Will they require that those who have received the Sputnik or the Sinopharm vaccine to get two more doses of Pfizer or Moderna? A total of four shots once they are in Canada?

And even if free and convenient campus clinics are set up, physical accessibility does not always guarantee actual access, just as the mere existence of food banks does not always prevent people from going hungry.

And what about people on the move, for whom international education is often a way to enter and stay in a Western country? Not only do they have to overcome the burden of crossing borders with a low-value passport, but they will also now face additional barriers from mandatory vaccine requirements.

A philosophical problem

COVID-19 vaccines do work. A study conducted by the U.S. Centres for Disease Control and Prevention found that an unvaccinated person is ten times more likely to become seriously ill or die from contracting COVID-19. In Canada, fully vaccinated people now account for only 0.5 per cent of new cases. The medical data clearly support mandatory vaccination.

But the argument is not medical in nature, but philosophical. The question we should ask is whether the allocation of rights in society should become conditional on a medical criterion that has been heavily politicized. COVID is being weaponized in all kind of ways to restrict mobility for those originating from developing nations. Being vaccinated confers a good enough protection for those lucky enough to reside in a rich country. We should perhaps ask why we should be entitled to 100 per cent protection when most of the world does not get any protection at all.

At stake here are not individual freedoms, such as the freedom to fly (most people in the world do not get to fly, since it is strictly those in rich countries that can afford it), or the freedom to attend a concert (if private corporations are mandating vaccines we have no choice but to accept that, as a direct consequence of privatization and conforming to the capitalist logic that governs our daily lives). What is at stake here are actual human rights — those that determine the social fate of a person — such as the right to education. Creating a precedent in allocating rights on a bio-political criterion is worrisome to say the least.

The public fight against vaccination requirements has been heavily weaponized by the political right and those privileged enough to complain about the inconvenience the pandemic poses to their individual rights, and the loss of privileges like travelling and entertainment. But a critique from the left, grounded in concerns for those who already have fewer rights, is equally valid and in need of a public platform.

Raluca Bejan is assistant professor of social work at Dalhousie University, in Halifax, Canada. She has a PhD and a MSW from the University of Toronto, and a BA in political sciences from Lucian Blaga University, Romania. Bejan was a former visiting academic at the Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS), University of Oxford, U.K., in 2016 and 2018.