There are clear indications that oil and gas companies will be given the green light soon to start “fracking” South Africa. Last week Water and Environmental Affairs Minister Edna Molewa made a speech that addressed fracking in South Africa. She reported that an interdepartmental monitoring committee is reviewing the existing regulatory framework for fracking and other technologies, including their impact on aquifers. She gave notice of government’s intention to declare fracking a “controlled activity in terms of section 38 of the National Water Act,” adding:

“What this means is that fracking becomes a water use, thus requiring a water use license. In this regard only matters concerning water resources will be of consideration when licenses are issued, including but not limited to the possible impact of substances and chemicals on the ground water resource.”

This notice includes all “exploration and/or production of onshore unconventional oil or gas resources.” The public has 60 days to comment.

After making this announcement, essentially signalling that fracking will go ahead, the Minister offered the shallow assurance that “our key priority is protecting the environment and our water resources,” taking “every precaution to ensure that the possible impact of fracking on our water is carefully managed and minimized.” Fracking uses high pressure, underground pumping of toxic chemicals, sand and water to crack open rock formations and release gas; there risks polluting ground water and soil and poisoning people, animals and the environment.

The aerial photograph above shows how the Olifants River was managed by the Department of Water Affairs in the face of open cast coal mining.

The 1960s exploration by Soekor for natural gas resulted in gas seeping into the borehole, still present in 2012 when this photograph was taken:

To date, organizing has focused on fracking in the remote and arid Karoo, but Karoo Action Group organizer Jonathan Deal has highlighted that fracking potential exists in the entire Karoo Basin, a vast area covering six of South Africa’s nine provinces. “Currently the focus is on the Shell proposal in the Karoo, but that is just the start of a much bigger march.”

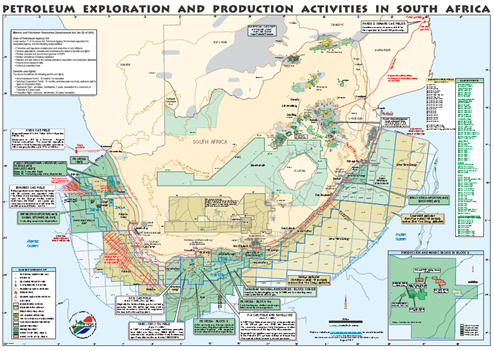

According to the latest exploration map on the Petroleum Agency of South Africa website, the Sungu Sungu gas, coal and petroleum group was given permission to seek exploration rights in several parts of KwaZulu Natal, including land adjoining the Maloti-Drakensberg World Heritage site and along the Mozambiquan border, including most of the Tembe Elephant Reserve. Two years ago Sasol and two foreign oil groups were granted similar permits covering a large portion of southern KwaZulu Natal, although they decided not to pursue exploration there for the time being (“Impact of Fracking to be Minimised,” The Mercury, 4 September 2013).

The Treasure the Karoo Action Group has threatened to go as far as the Constitutional Court to block “fracking.” With organizer Jonathan Deal on board, honoured earlier this year with the international Goldman Environment Award for his anti-fracking campaigning, the South African government is best advised not just to give notice, but to take notice.