The film Lost Rivers, which was the opening presentation for the Planet in Focus Film Festival last night in Toronto, charts the fate of six rivers buried underneath six cities across the globe.

Human beings require water to survive. For this reason virtually every city in the world is situated in relation to proximity to water. Most inland cities rely on a river or aquifer for their survival. Rivers once served as highway, food source, power source, as well as source of fresh water. But industrialization and concomitant increased population densities created another purpose for urban rivers. They became sewers. As such, rivers also became a source of waterborne disease. To resolve this, the same industrial hegemony that spawned the sickness, gave rise to the final solution for rivers. In the late 19th century, many cholera carrying urban rivers were buried beneath the cities they once nurtured. Thus their existence as living arteries thus ended, and these rivers were transformed into de facto storm drains.

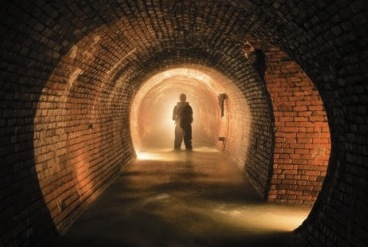

Despite its dangers, city dwellers are naturally drawn to water. This was a curse in the absence of sanitation. But now it is part of the answer to making cities more natural and live able. “Lost Rivers” follows “drainers”, river keepers for invisible rivers. These drainers spelunk these underground waterways documenting the arachaeology of these lost rivers in the hope of restoring them to nature.

In Brescia Italy, the local “drainers” are called the Brescia Underground. Brescia is a medieval city built over a network of seven rivers. However much about the history and location of these rivers has been forgotten. The Brescia Underground started as a group of urban spelunkers looking for an underground thrill. But as they became more active in exploring their cities rivers, the Brescia Underground morphed into a historical society. They currently conduct underground tours documenting the history of Brescia’s rivers and reviving their history in the hearts of the city’s inhabitants. Currently they are seeking to find the location of a lost lake and washing platform from a renaissance painting. This group of explorer activists have put their city’s lost rivers back on the map, if not back on the actual landscape.

But Lost Rivers is not merely a historical document about lost rivers, nor a litany of the human industrial hubris that buried six urban waterways. It is a blueprint for restoration through the “daylighting” of these rivers.

In Seoul Korea In Seoul Korea, a stream formerly buried under a 16 lane double deck highway was recently daylighted. For decades the river ran under a clogged traffic artery which divided the city, and caused traffic chaos. A courageous decision was made by city planners to tear down the highways and restore the river. Cheyonggycheon stream is now the central feature of an urban river park and promenade. It is reminiscent of the banks of the Seine, with urban waterfalls, and fish. Improved public transit relieved the congestion that the highway created. Now Local retirees care for the newly created urban river with care and purpose. An urban river lives again, and a city exists in a more human city because of it. The temperature and dust levels of the city have also subsided for having chosen a river over a highway.

In Yonkers New York, the 19 mile long Sawmill River was buried under a parking lot for ninety years. Like other rust belt cities, Yonkers is characterized by urban decay. The last thing Yonkers needs is a parking lot. In order to revitalize itself, the city of Yonkers decided to unearth this river. Millions in future tax revenues and the assistance of all government levels were required in order to undo the industrial damage that was done by burying a river. But just six months after daylighting the Sawmill river, fish swim in it anew. And downtown Yonkers, formerly a rust belt basket case, appears to be on its way to becoming a revitalized modern neighbourhood. Nature will have recovered what economics had abandoned.

In South East London, flood control has also taken the form of daylighting the Craggy river. By creating an artificial floodplain in a park, storm water is stored in a natural setting until it can safely flow into the watershed. This is a far superior solution to the continuing flood problem than more concrete channeling dirty, exhausted water. This plan had the dual benefit of creating a new natural urban space, and of storing storm water so as not to overwhelm the storm drain system in the age of increasingly historic downpours.

But in Toronto, no such plans are envisioned for one of that city’s buried rivers. Garrison Creek runs below Toronto’s Trinity Bellwood’s neighbourhood. Local residents annually do a “river walk” along it’s length to mourn it’s disappearance from the urban landscape. Any visions of daylighting even the part of the river running beneath a city park are purely pipe dreams. Despite the fact that houses along Garrison Creek’s underground course are slowly sinking, Toronto remains mired in the industrial mindset of yore. Toronto planners have rejected natural watershed plans in favor of a four kilometer long underground storm water storage system which cost the city billions. This will eventually be extended to 22 km stormwater storage tunnel costing Toronto many billions more. When it comes to recovering its rivers Toronto is a laggard. Torontonians are reduced to mourners, annually tracing the route of their ghost creek.

Lost Rivers is all about its subject. Director Caroline Bacle tells the story of these rivers with little resort to cinematic artifice. Her own presence as a narrator in the film is unobtrusive. Alexandre Domingues’ photography is crisp and clean, like pure water. Howard Goldbergs’ editing too flows effortlessly, and is unsensational. Nothing in the film calls attention to itself lest it intrude upon the story of these rivers. But Lost Rivers is meticulous enough to balance even the rivers’ story against short term economic interests. The economic cost of construction projects to daylight rivers is given voice through business people who have had to survive the process in Yonkers and Seoul.

But in the end the story of buried rivers is most compelling because humanity’s most astonishing transformation is not watershed landscapes, but the global climate. The solution of burying the rivers in a time of cholera will not stand in the coming deluge.

Humberto DaSilva is a union activist whose ‘Not Rex Murphy’ video commentaries are featured on rabble.