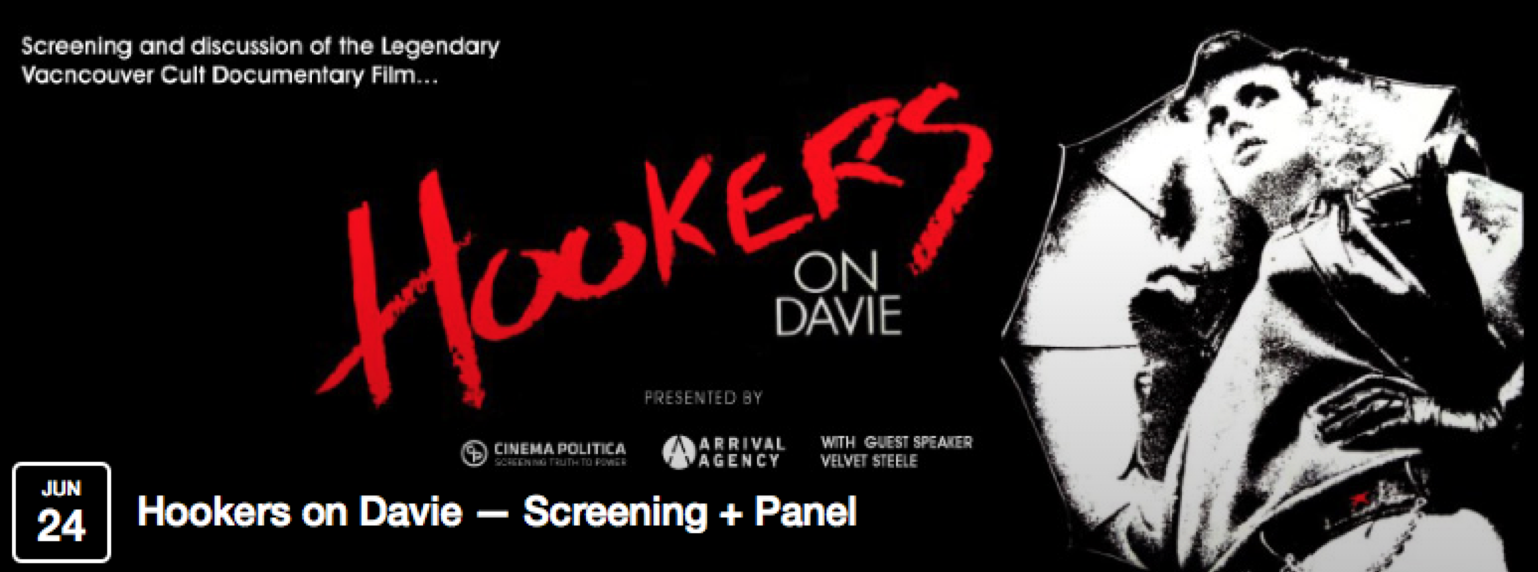

Hookers on Davie, a documentary from the 80s, was screened on June 24 at the Fox Theatre, a venue which caters to mostly white, liberal twentysomethings. The demographic who regularly attend events (music shows, burlesque, etc.) at said venue, were also the demographic who attended the screening. I did not see any local activists, feminists or other people I recognized from communities, other than a few familiar faces from the UBC feminist community. I question if the individuals present were there by default, as the pro-sex work movement seems to be supported blindly because it’s the “left” thing to do. The documentary and panelists gave some historical context for the film although the history presented did not reflect the reality of all women working in the sex industry, as the subjects of the film were predominantly white. It was clear to me that many of the viewers had no historical or contextual understanding of prostitution laws in Canada, or the recently tabled prostitution legislation: Bill C-36.

The aim of the documentary was to present the sex industry as a vibrant community and a self-supporting, pimp-free environment, while demonstrating the humanity of the subjects. The documentary did not focus on male violence, nor did the panel. Yet each subject describes accounts of male violence, wherein the life of the subject was endangered. There was mention of incest, rape, battery and intimidation with a weapon, yet none of the panelists invited dialogue regarding violence against women, nor did the viewers during the question and answer period. The documentary attempts to frame the purchasing of bodies for sexual use, as simply “work” — a transactional, normative, and otherwise “safe” form of labour. By framing prostitution as labour, the pro-sex work movement is now understood to be a labour rights movement, rather than a liberationist movement. The pro-sex work ideology suggests that women can be empowered within a patriarchal capitalist white supremacy, as long as we are protected by a state which creates the conditions for women and girls to be subjected to male violence.

The documentary aims to construct an image of a john as a “nice guy” or a “normal” guy in order to give the impression that “normal men” do not perpetuate violence against women — that doctors, lawyers, and business owners are not the perpetrators of violence. This is a myth often perpetuated by the pro-sex work movement — that “not all men” perpetuate violence, not all men are privileged by patriarchy.

But the construction of the “nice john” is contradicted by the stories of male violence told by each of the subjects in the film. One of the panelists later revealed that Candice (one of the documentary subjects) was murdered by a client, a regular john of hers. The “nice john” construct is also unpacked as women subjects share stories about the performances which they enacted for johns, such as daddy-daughter role play. Male buyers and male sex trade supporters view women as objects under patriarchy; their material and psychological harm rendered irrelevant.

Most women in the documentary described discontent with their work as prostitutes and admitted to entering prostitution to escape the conditions of capitalism and earn wages. Many of the women’s experiences with prostitution began as children/teens (12-14 years old). And still there was no discussion of male violence. By ignoring the issue of male violence, the material reality of women in prostitution who face violence at the hands of men is trivialized and the perpetrators are not held accountable. While I attempted to digest the metanarrative of the documentary, some man beside me (older, white) showed his empathy for the female subjects by pitying their experiences, wondering how this could happen to women. The answer is that violence against women is assiduous — it is cultural, institutional, social. It is romanticized, sexualized and accepted. Because there are dialogues about prostitution that do not address male violence.

The documentary attempts to destigmatize prostitution and the women who are the majority of prostitutes. The audience was charmed by Michelle (woman subject) and the fierce personality and humour she possessed. Prostitutes are real people with personalities and feelings. This is not a radical notion. Pro-sex work lobbyists are not the only organizations fighting for the rights of women’s personhood. Yet, the work and activism of feminists are demonized by the pro-sex work lobby — bolitionist groups, for example, are unjustly compared to the conservative right (not-in-my-backyard types). The comparison is justified on grounds of language similarities, as abolitionists frame prostitution as an inherently sexist, violent act — a form of exploitation. This argument is not rooted in conservative moralism, though. The abolitionist stance refuses to demonize the prostituted woman, but rather assigns blame to the perpetrators of violence, the state, and the dominant sex. Unlike NIMBYs, both historically and contemporarily (such as the 1984 injunction), feminists who oppose the sex industry address the hierarchies which exist within prostitution and that create a context within which the sex trade can exist(race, sex, and class) and the systems of oppression which are exercised. Feminists are not attempting to erase prostituted women and their experiences, but rather criticize the conditions which allow exploitation to manifest.

The panelists placed a high emphasis on “choice.” As Velvet Steele said, a job is a job and “we all choose our professions.” This seems a rather glib statement, as the praxis of our choices is influenced by a variety of contexts, such as gender, class, and race. The panel refused to acknowledge the hierarchies of race, sex and class which exist within prostitution, and that, often, women do not have the social or economic capital to exit the industry.

The argument of “choice” is emblematic of the neoliberal political and philosophical ideology of the status quo. This ideology places emphasis on the individual and individual agency, and ignores a class analysis. Moreover, women as a class are divided by hierarchies such as race and class, yet the liberal model is still applied. Not all women choose. The individualist approach was reflective of the climate of privilege of the event, similar to the Bedford decision which protected the rights of a particular class of sex workers, not Aboriginal women and street level prostitutes. The documentary (and the panel) provided a poor representation of the reality of sex workers in Vancouver, whether or historical or not — Aboriginal women were not represented in the film, despite the fact that Aboriginal women are overrepresented in street prostitution.

What most concerned me was the reality that the demographic which attended the event were mostly liberal/progressive types who support pro-sex work rhetoric by default and do not think critically about why prostitution is harmful. The panel condemned abolitionists, the Nordic Model and second wave feminists. Becky Ross (a UBC gender studies professor), for example, said that second wave feminists did not understand prostitution as a labour issue. I was very disturbed by the UBC academics framing of second wave feminists as conservative and ahistorical. The second wave challenged patriarchy and capitalism; the institutions which divided women and men’s labour. Prostitution is gendered — even if viewed solely as a form of labour — and despite the “men involved in prostitution,” women make up the vast majority of prostitutes. As we know, men are the buyers of sex, whether it be the bodies of women and girls or other men.

The demographic in attendance absorbed the information without question or hesitation.

Misinformation concerning the abolitionist approach and second wave feminism is rampant; I have experienced it within my university community, for example, when a male “activist” argued that abolitionists want to criminalize women. This is one example but there are countless instances. I have experienced the disregard for second wave feminists, the myths about our foremothers and their attempts to dismantle patriarchy. This is the demographic who will be infiltrating academia and cultural avenues, the liberal twentysomethings who simultaneously got wasted while discussing the contingent issue of Canadian prostitution laws in Canada.

The question and answer period was dominated by (white) male voices — men who explicitly supported sex work reform. I wanted to vocalize my concern regarding the lack of women of colour and Aboriginal women within the film and the discussion, but I did not. I did however discuss this issue with one of the panelists following the Q&A but she did not have any substantial reason for the invisibility of Aboriginal women within the film and the panel. Basically she said that Aboriginal women and women of colour need to represent themselves and tell their stories. I agree, but also their absence from the film and the panel presents a misleading vision of prostitution in Canada, historically and contemporarily.

As I walked home I attempted to digest the event, which was followed by a dance party. I was infuriated by the selective representation of prostitution in Vancouver, which constructed an image of prostitution which does not reflect the material realities of women. The whole event was about framing the pro-sex work agenda as progressive, while framing the abolitionist position as counter-progressive, prudent, conservative and moralist.

Are we going to challenge the capitalist patriarchy which allows for women and girls to be exploited and subjected to violence? Or will we blatantly accept the idea that men exercising their economic and social capital is simply a transaction between consenting adults? The framing of the sex industry as an opportunity for women to exercise their agency is a transparent attempt to liberalize the issue and normalize systems power. Granting women equal access to a patriarchal society, a structure which exists only to benefit the dominant sex, will not liberate women as a class, especially those women who are most affected by systems of oppression, whether they are performing sexual labour or not.

Emily Monaghan is a second-year student at UBC, a member of the Guerilla Feminist Collective and an organizer for TBTN UBC. Predominantly disgusted by the pop culture feminist climate of the status quo.