On July 8, the U.S. State Department announced the launch of a Commission on Unalienable Rights, which is intended to rethink and reshape how human rights laws are applied around the world. This commission was deemed necessary to ensure that “human rights discourse not be corrupted or hijacked or used for dubious or malignant purposes,” though in that founding statement, the department failed to explain how this was supposedly happening, or who was said to be hijacking said discourse.

Reporting about this development immediately raised concerns that the commission’s mandate could negatively impact and specifically target LGBTQ human rights protections, and there could be dire ramifications for reproductive rights, sex-based rights, and the rights of migrants as well. Although the wording of the announcement is vague to a degree, religious conservatives clearly expect the project “to address concerns about religious freedom and abortion,” at the least.

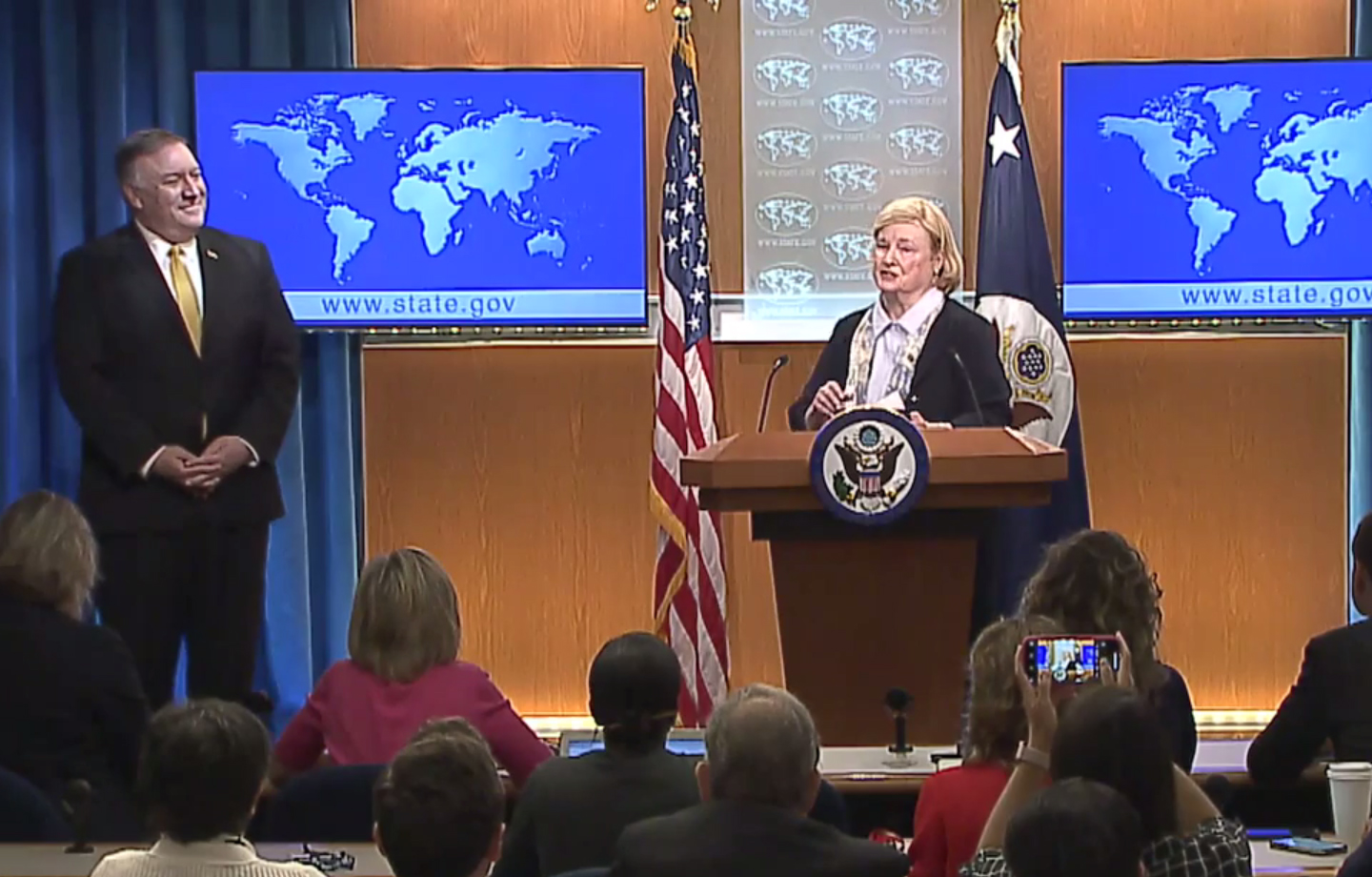

In announcing the Commission, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo rationalized that by delineating protected classes in human rights laws, “politicians and bureaucrats… blur the distinction between unalienable rights and ad hoc rights granted by governments. Unalienable rights are by nature universal. Not everything good, or everything granted by a government, can be a universal right.”

This is a common talking point among religious conservatives, who argue that human rights cannot be granted by “politicians and bureaucrats” (i.e. courts and human rights commissions), but by God alone. The given rationale for that thinking is that human rights should be subsumed under “natural law and nature’s god.” Certainly, when this Commission on Unalienable Rights was first announced at the end of May, the State Department lamented that human rights “discourse has departed from our nation’s founding principles of natural law and natural rights” — although this phrasing proved to be so transparent to media outlets that the word “natural” was absent from this week’s launch.

Of course, fixating on nature is a fallacious way of limiting rights to exclude the obvious intended targets. Same-sex coupling occurs in nature. Changing sexes occurs in nature. Reproductive limiting and parental choice occurs in nature (though the means can seem shocking and visceral). Polyamory occurs in nature. What doesn’t occur in nature is “one-man-and-one-woman marriage,” and life-long monogamous exclusivity is only practiced by three to five per cent of mammals (including humans) and even less so in other species.

But make no mistake: excluding classes of people from human rights law is clearly the intention. Any attempt to more narrowly define whose rights are “unalienable” and therefore legitimate is, by reflection, also an exercise in determining whose rights are illegitimate, and therefore… alienable (perhaps even in the truest meaning of that word.)

While the State Department denied that the Commission would address “policy questions” like abortion rights, they asserted that it would instead “attempt to ground human rights in the founding principles of ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.'” That said, the Commission’s mandate never appeared designed to address specific issues or classes, but rather to create a rationalized hierarchy or criteria through which the exclusion or trumping of disfavoured rights becomes logically inevitable — which is a bit of semantic sleight-of-hand.

When the Commission on Unalienable Rights was first announced, it was originally to be under the auspices of Princeton professor and co-founder of the National Organization for Marriage, Robert George, who reportedly drafted the original concept note and is described by peers as “revitalizing a strain of Catholic natural-law thinking that goes back to St. Thomas Aquinas.” Like the word “natural,” George is also absent from the launch, but the Commission’s roster is so overwhelmingly linked to him that its membership was almost certainly hand-picked by him.

The Commission is chaired by Harvard Law professor Mary Ann Glendon, the former ambassador to the Vatican and an anti-abortion activist, who served on the U.S. Commission on Religious Freedom (from 2012 to 2016, with George). She is a board member of the anti-LGBTQ+ funding group, Becket Fund, and is perhaps best known for fighting on behalf of the Holy See to prevent the inclusion of abortion rights at the 1995 UN World Conference on Women in Beijing.

Glendon has made many troubling statements, such as publicly condemning the Boston Globe’s expose on abuse within the Catholic Church, in 1992; referring to marriage equality as a “radical social experiment” and “not a civil rights issue, but a movement for special preference”; complaining that religious freedom is “subordinated to a whole range of other rights, claims and interests”; and calling for a “flexible universalism” in which human rights are not standardized, but contextualized according to (she quotes from the 1993 Vienna Declaration) “national and regional particularities and various historical, cultural and religious backgrounds.”

In her book, Abortion and Divorce in Western Law, Glendon clearly sees abortion as an infringement on the rights of the fetus, and no-fault divorce as an infringement on the rights of children. Glendon is also not known for compromise, going as far as rejecting a medal from the University of Notre Dame because that institution also conferred then-President Barack Obama with an honorary degree, despite the fact that he supported abortion access.

For what it’s worth, she also a hired Pompeo as a research assistant, when Pompeo studied law at Harvard.

Joining Glendon is a smorgasbord of Robert George-linked and similarly minded academics:

- Peter Berkowitz, a senior fellow at the Hoover Institute who responded to the overturning of sodomy laws by condemning U.S. Supreme Court Justice Kennedy for allegedly failing “to subject the Texas statute prohibiting homosexual sodomy to ‘rational scrutiny.'” Berkowitz calls for religious conscience to be “unhampered by government coercion,” and has written several other treatises opposed to LGBTQ+ human rights.

- Paolo Carozza, a Notre Dame law professor and long-time critic of human rights laws who, among other things, advocated for a Vatican-tinged flavour of “human dignity” as a determinate for legitimacy of human rights.

- Shaykh Hamza Yusuf Hanson, an influential American-born convert to Islam and co-founder of Zaytuna College. Yusuf told religion writer Scott Korb that “I don’t want to see gay people bashed… But I also don’t want it normalized as a healthy thing for a society… I don’t want someone to say this is a normal, healthy lifestyle. It’s not. It’s pathogenic…'”

- Jacqueline Rivers, a Harvard sociology professor, and co-founder and former executive director of the Witherspoon-sponsored Seymour Institute for Black Church and Policy Studies. Rivers is an anti-abortion speaker, and GLAAD also noted that she once “insisted that marriage equality activists are undermining the Black Civil Rights movement [by demanding human rights protections], but comforted the applauding attendees by telling them ‘God will not be mocked…'”

- Rabbi Meir Yaakov Soloveichik, a spiritual leader of Shearith Israel, the oldest Jewish congregation in the U.S. Soloveichik argued that the legalization of same-sex marriage would lead to the normalization of bestiality.

- Katrina Lantos Swett, president of the Lantos Foundation for Human Rights and Justice. She has been pointed to as a Democrat involved with the Commission (as though she makes the project bipartisan) — but Swett is still a “religious freedom” advocate with a Mormon-leaning multi-faith background, who was also on the U.S. Commission on Religious Freedom, along with Mary Ann Glendon and Robert George — the latter of whom reassured religious conservatives that “She was the very opposite of a partisan or an ideologue… I did not have a different vision from Katrina, and she didn’t have a different vision from me. We were the same.”

- Christopher Tollefsen, a University of South Carolina professor, senior fellow of the Witherspoon Institute, prolific religious conservative writer, and co-author of the anti-abortion and anti-stem cell research book Embryo (with Robert George). Tollefsen is a devotee of Paul McHugh when it comes to trans issues, and has argued that it is not only not possible to change sex, but also “a mark of a heartless culture” to make surgeries and affirming, non-psychological treatments available to trans individuals.

- David Tse-Chien Pan (a professor at the University of California at Irvine) and Russell Berman (a Stanford University professor and a senior fellow at the Hoover Institute) are less clear, but Pan is a critic of “liberalism” (libertarianism), and Berman (not to be confused with a writer at The Atlantic by the same name) appears to be a critic of Islam, “left-fascism” and “campus anti-Semitism,” which may refer to protests in support of Palestinians.

- Named in only some of the announcements are Kiron Skinner (State Department director of policy planning, who “ignited controversy in May for framing the contentious U.S.-China relationship as ‘the first time that we will have a great-power competitor that is not Caucasian'”), and attorney F. Cartwright Weiland (Rapporteur), who was a Council for Life panelist, helped write amicus briefs supporting laws restricting abortion, and is a critic (in an article expounding on board chair Mary Ann Glendon’s 1991 writing about Rights Talk) of “identity politics” and LGBTQ+ inclusion in human rights.

It’s important to contextualize all of this within the current developments in the United States under the Trump administration. Catholic and Evangelical fundamentalists (who I feel are important to differentiate from other Christians, despite their sadly often successful habit of passing off their political causes as the “Christian” position) are already seeing legal successes in restricting abortion access, and expect an overturn of Roe v. Wade (and perhaps even Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized same-sex marriage) by a newly stacked conservative Supreme Court, very soon — and have been looking for directions to refocus, in order to maintain their momentum, power and following. One of these directions has been to make abortion “unthinkable,” while another has been to formalize a means for religious freedom and religious conscience to override LGBTQ+ (and other) human rights protections. A deeply biblical rewriting of human rights law could not only create a license for anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination, but also completely undermine reproductive rights and entrench vastly outdated ideas about gender roles, including theological notions like “complementarianism.” For example, ThinkProgress recently noted that if a case of the so-called “Billy Graham Rule” (of religious fundamentalist men refusing to meet with women without a chaperone) were to proceed to the rightward-shifting U.S. Supreme Court while using a “religious conscience” argument, it could very well provide the basis for a legalization of sex-based discrimination, at least under specific circumstances.

This Commission is also taking place during a severe, self-inflicted crisis of anti-immigrant policy in the U.S., which has seen detention camps with atrocious conditions rightly criticized and noted for their historical parallels (even if not necessarily identical matches to past atrocities). Religious conservatives have not simply turned a blind eye to these developments, but have actually often collaboratively helped to create rationalizations for these brutal policies (especially when it comes to Muslim migrants). In this context, and under the auspices of a government that has very clearly shown the will to dehumanize migrants and refugees and trample their rights, it is not inconceivable that this Commission is designed to provide a structure by which a lesser human status for migrants is potentially justifiable.

This Commission is also contemporary to Trump’s stated intent to decriminalize homosexuality worldwide. This inevitably brought some pushback from his religious base — but only a little, while other figures took the opportunity to try to appear diplomatic, seeking to realign the centre of the LGBTQ+ rights versus religious freedom (false) dichotomy by “calling for an end to all forms of physical violence against homosexuals — but [also to] refrain from imposing the values of the sexual revolution on the rest of the world.” Although the administration’s decriminalization project appears to have been driven more by U.S. ambassador to Germany Richard Grenell than by Trump himself, it is also not irreconcilable with a mandate like the Commission’s: ending overt criminal prosecution is a far cry from supporting actual human rights protections, which are a far greater level of enfranchised citizenship, and facilitate the ability to participate in society as a whole. The Commission on Unalienable Rights doesn’t have to obliterate what it determines are “illegitimate” human rights classes entirely, in order to legalize discrimination against them — it only needs to create a hierarchy which elevates those rights that it determines are “unalienable.”

And finally, this comes at a time when religious fundamentalists have successfully engineered the illusion of several false dichotomies to create the impression that human rights create irreconcilable conflicts: of LGBTQ+ rights versus religious freedom; of personhood rights versus reproductive rights; of trans rights versus sex-based rights; of parents’ rights versus children’s rights (though this is often treated as though the latter are non-existent); of all human rights classes versus freedom of speech; and more. Of those, personhood rights are based on a faulty premise that an undeveloped fetus that cannot exist on its own is somehow a person, and (for the most part) the remaining dichotomies are only irreconcilable if the party that wishes to do harm to the other inflexibly insists that it cannot compromise under any circumstance whatsoever — and will do whatever is necessary to frame any particular pressure to do so as persecution.

What all of this points to is a project that appears designed to rethink human rights as a structure in which some humans can be lesser. And this is concerning, if it becomes the template by which the U.S. proceeds to push human rights discussion on the world stage, in the coming years.

If the launch of the Commission on Unalienable Rights is any indication, terms like “natural law” may be stealthily replaced by language that is far more opaque, and carefully designed to appear as though it does not target any specific groups. But in all likelihood, it will nevertheless still prioritize things like religious conscience, “dignity” (redefined as a god-granted status that is infringed upon if we make certain life choices about sexuality, a popular theme in Catholic-based discourse on “natural law”), personhood (a dog whistle that frames the fetus as a person), and (though I have not touched on it here, but it can be seen in the battles over sex education) parents’ rights, among other characteristic themes that merit further exploration.

I am sure that we will find out soon enough.

Mercedes Allen is a graphic designer and advocate for transsexual and transgender communities in Alberta. She writes on equality, human rights, LGBT and sexual minority issues in Canada, and the cross-border pollination of far-right spin. This blog also appears on DentedBlueMercedes.