Content warning: The following contains descriptions of torture, abuse, suicide, and sexual assault. Please proceed with caution and care. If you require support, there are resources available.

How do you not care when something is absolutely wrong? What do you do when you are ahead of the national and international reality? How do you speak about an issue when there is an absence of language to describe and address it?

These were some of the questions faced by non-State torture (NST) activists Jeanne Sarson and Linda MacDonald. The former public health nurses from Truro, Nova Scotia answered a late-night call from Sara*, a young woman who was going to kill herself in five days. That began a nearly three-decade journey to have NST recognized.

Since childhood, Sara’s life meant being tortured relationally and there was no one who cared nor anyone brave enough to help her.

Her abusers included her parents, their friends, other family members and strangers. Sara had been conditioned since childhood to commit suicide whenever she contemplated revealing the abuse. There was no language to describe this type of indoctrination. It was Sarson and MacDonald who created the term “femicide conditioning” — a form of abuse meant to invisiblize both the NST victim and the human rights crimes committed against them.

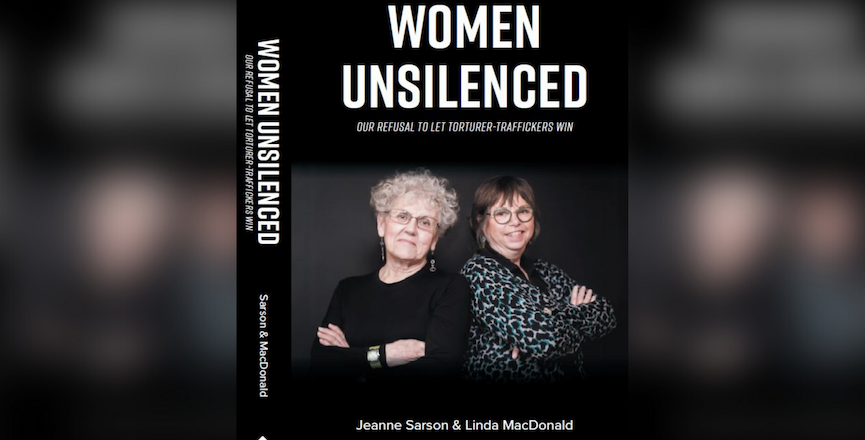

People literally ran from Sarson and MacDonald when they began speaking out about NST. But they persevered with their ground-breaking work which they recount in their newly released book, Women Unsilenced: Our Refusal to Let Torture Traffickers Win.

Lynn* was held captive and trafficked by her husband and three of his friends. Police officers, who were on duty, were among those who sexually assaulted Lynn. A gun was often left on the bed beside Lynn or placed down her throat while the assaults took place.

The only option for NST survivors like Lynn is to charge each torturer with sexual assault or aggravated assault for every individual act. In Lynn’s case, that would require police to lay hundreds of individual charges resulting in decades of litigation and potential appeals. With a 0.003 per cent of sexual assault cases ending in convictions in Canada, pursuing legal avenues is futile.

Sarson and MacDonald had hoped the federal Liberals would institute legislation making NST a crime in Canada. Instead, the private members bill introduced in February 2016 by Liberal MP Peter Fragiskatos that would have recognized NST died on the floor on November 29, 2017.

To date, Sarson and MacDonald have been contacted by thousands of women not only from Canada, but from around the world.

Sarson and MacDonald are now joining forces with global advocates to ensure enforcement of Article 5 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is applied as a human right to all women and girls. To that end they are backing the creation of a new legally binding treaty on violence against women and girls. The enforcement of the Every Woman treaty would be carried out by an independent monitoring body. Their goal is to get the Canadian government to adopt the Every Woman treaty.

Sarson says she “hasn’t given up hope that the torture that takes place in private will be recognized.”

Sarson and MacDonald uncovered a side of family life most would like to pretend doesn’t exist. Their book gives NST language that empowers and gives agency to survivors.

At the same time, their book arms advocates determined to get the Canadian government to finally acknowledge and enforce NST as a crime.

Sarson and MacDonald have opened the door for everyone including police, lawyers, judges, teachers, nurses and mental health workers to provide caring and compassionate services for those living with and recovering from NST.

As MacDonald stated: “It’s time to end the global war waged against millions of women and girls.”

To order a copy of Women Unsilenced: Our Refusal to Let Torture-Traffickers Win click here.

*Names changed for privacy.

Doreen Nicoll is a freelance writer, teacher, social activist and member of several community organizations working diligently to end poverty, hunger and gendered violence

Image: Jeanne Sarson and Linda MacDonald/Provided