The Canadian Wheat Board (CWB) has been at the intersection of political controversy. The Harper Government’s Bill C-18 (which came into effect on August 1, 2012) legislated an end to its monopsony (a single buyer facing many sellers) as purchaser of Canadian wheat and barley. Given the importance of the CWB in protecting individual grain farmers from the immense marketing force of multi-national corporations on the one hand, and the determination of the Harper Conservatives to splinter the collective muscle of the CWB on the other, this is hardly surprising. What is surprising is the normally staid CWB being at the center of a controversy in a clumsy attempt to foster participation with a sexually charged advertising campaign.

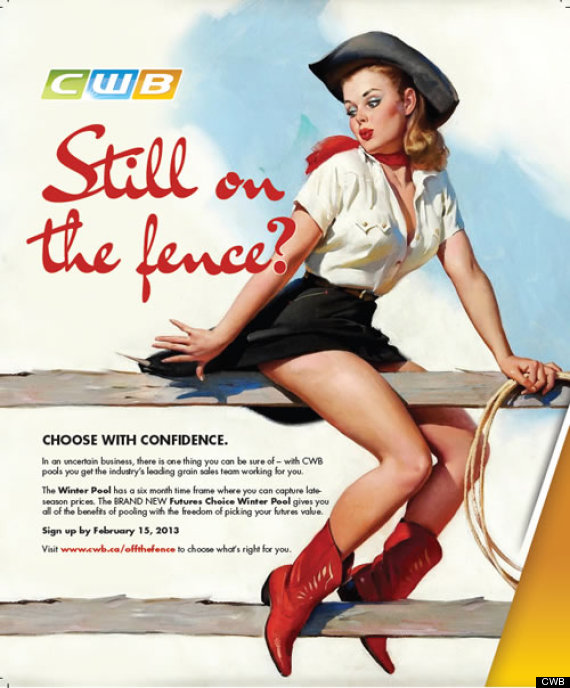

“Still on the fence?” asks the CWB ad, featuring a sexy cowgirl with ample bosom, prominent cleavage, cherry red lipstick and sultry eye-shadow, a skirt hitched to her waist, and a fence railing provocatively positioned between her naked thighs. Did the CWB perhaps get “barely clad” mixed up with “barley clad”? Are they confused about the meaning of ‘stimulating’ sales? Who knows?

The Canadian Press reports that the National Farmers Union is questioning what this image has to do with a soliciting farmers to participate in the Wheat Board to get the best prices for their product and procure the assistance of a “leading grain sales team.” Joan Brady, head of its women’s branch said:

“I really didn’t appreciate first of all, the image that it gave to rural women or women on the farm. Secondly … if I was involved in a western wheat farm … that would turn me off pretty much very quickly because it dismissed me as a farm operator.”

In Parliament, NDP MP Niki Ashton, the official opposition Status of Women Critic, called onAgriculture Minister Gerry Ritz (the Minister responsible for the CWB), to pull down the ad saying that the CWB is “reverting to 50s pin-up ads to sell wheat.”

CWB spokesperson Dayna Spring replied that, “We wanted to be provocative, we wanted it to get attention, but it was certainly not our intention to offend anyone. We have no plans to stop running it.”

Responses have ranged from “derogatory and disgraceful,” to “there are more important things,” to “Who cares?” Is the CWB ad harmless, titillating, attention-getting fun or stereotypical sexism?

From a woman’s perspective

I’m not a woman and wouldn’t pretend to speak for women. Nevertheless, from a feminist perspective I think the jury has long been in on images of this sort. Even in 1969 when the print (Hi Ho Silver by prolific pin-up artist, Gil Elvgren) on which the ad is based was created, it already presented an archaic view of women. It’s been exacty 50 years since Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, often considered as the beginning of the so-called second wave of feminism, was published (February 13, 1963). It’s now 2013 and the impact of such “soft-porn” representations of women are well understood. Many find imagery that that objectifies them, reducing them to sexual stereotypes, to be demeaning and humiliating. And it shouldn’t be hard to understand why this is so. In a contemporary world, women have every right and expectation that they will be treated seriously on their own merits. Stereotypically reducing them to their value and attractiveness as male-defined objects is a slap in the face. It’s no less insulting than stereotypical images of blacks, gays, Jews, Indians, gypsies, or any other identifiable group. No organization would run an ad campaign using stereotypical blackface, Uncle Tom; sexualized bimbo images of women should be similarly beyond the pale.

I’m not a woman and wouldn’t pretend to speak for women. Nevertheless, from a feminist perspective I think the jury has long been in on images of this sort. Even in 1969 when the print (Hi Ho Silver by prolific pin-up artist, Gil Elvgren) on which the ad is based was created, it already presented an archaic view of women. It’s been exacty 50 years since Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, often considered as the beginning of the so-called second wave of feminism, was published (February 13, 1963). It’s now 2013 and the impact of such “soft-porn” representations of women are well understood. Many find imagery that that objectifies them, reducing them to sexual stereotypes, to be demeaning and humiliating. And it shouldn’t be hard to understand why this is so. In a contemporary world, women have every right and expectation that they will be treated seriously on their own merits. Stereotypically reducing them to their value and attractiveness as male-defined objects is a slap in the face. It’s no less insulting than stereotypical images of blacks, gays, Jews, Indians, gypsies, or any other identifiable group. No organization would run an ad campaign using stereotypical blackface, Uncle Tom; sexualized bimbo images of women should be similarly beyond the pale.

Context is important. The CWB ad isn’t an advertisement for a cowboy/cowgirl burlesque night, or for a gallery exhibition on historical imagery in advertising. It is a solicitation for farmers to participate in the Wheat Board. Moreover, the CWB is a public institution, created in 1935 by statute by the Canadian Parliament with a Board of Directors appointed by the federal cabinet on recommendation of the Minister of Agriculture. The CWB is selling grain, not adult films. What’s it doing running ad campaigns like this?

Today in Canada women play a vital role in agriculture. In 2006, Statistics Canada reported that 27.8 per cent of farm operators were women, making up 40 per cent of operators on multiple-operator farms. Women are owners or co-owners of farms, work hands-on in farm operations (a third of women operators work full-time on their farms), and make decisions about every aspect of farm operations. A representation of women as sexualized objects doesn’t reflect the reality of farm life in Canada in 2013. What are the many female farm operators to make of the “Still on the fence?” campaign? Advertising based on such imagery is inaccurate and insulting — and not apt to achieve its objective (soliciting farmers to participate in the Wheat Board’s activities; see below). As Joan Brady points out, such ads are apt to alienate women.

From a man’s perspective

Although I’m a man, I also can’t pretend to speak for all men. I can, however, say this. “Still on the fence?” is designed to press sexual buttons. If you are a heterosexual male, you will pay attention to the image. It’s programmed in the genes.

Although I’m a man, I also can’t pretend to speak for all men. I can, however, say this. “Still on the fence?” is designed to press sexual buttons. If you are a heterosexual male, you will pay attention to the image. It’s programmed in the genes.

Advertising is designed to be manipulative. That is, after all, the whole point. To make us pay attention and desire things. Anyone who has any doubts on this score need only to listen to a single episode of Terry O’Reilly’s brilliant radio series, Under the Influence. Advertising is the rapier edge of western materialist consumerism. Even so, I resent having my genetic buttons pushed by ads like this. There are plenty of ways to sell, some more honest than others. “Still on the fence?” resembles the archetypical automobile ad with a scantily clad, sexy girl perched on the fender. “Buy this hotrod,” says the subliminal text, “and this chick will be yours.”

We live in an increasingly hyper-sexualized world. Concern has often focused on young women, processing such messages while trying to develop their own self-images. However, it’s a concern in relation to men as well. A culture saturated in sexually provocative material sends unending stimuli at men, which consciously or unconsciously elicit Pavlovian sexual responses. This is cultural static being broadcast at us that we unendingly need to filter out.

I find the sexual clutter that is being constantly directed at women — friends, partners, daughters, and sisters — disturbing. Ads like “Still on the fence?” place women in a figurative garage, walls plastered with pin-up girls. They find themselves stuck, not knowing where to look, while the grease monkeys tinker away, and left wondering “If this is how these guys see women, what are they thinking about me?” Such sexual stereotyping and objectification pollute gender relations. They are an elephant in many rooms that repeatedly needs to be escorted out before normal gender relations can resume.

Getting off the fence

What does all of this tell us? In a scrambled and disjoined note, Warning: not safe for work (outside city limits anyway), the object and focus of which is unclear, Mcleans writer Colby Cosh tries to stir up sentiment against what he terms “irony phobic socialists” by saying, “Heavens, what sort of literalist doofus cavils at the sauciness of a Gil Elvgren painting in the year 2013? Even in their original setting the point of these pin-ups was innocent flirtatiousness, as opposed to pornographic frankness.” Cosh tries to justify the ad campaign arguing “My own interpretation of the ad, if I may dare advance one, is that the CWB, having been obliged by the government to compete for farmer business, is going out and competing for it.” Really?

In It turns out sex doesn’t sell. Someone should tell the Wheat Board in the Globe and Mail, Shari Graydon, the founder of Informed Opinions and an incisive analyst of advertising, points out that:

“Although viewers may remember a sexy image, they often won’t recall what it’s promoting. And even then, it isn’t likely to motivate buying behavior unless the product or service on offer is actually associated with sex.… More importantly, the use of sex in an advertising campaign has as much capacity to alienate as it does to appeal.”

Perhaps in a distant pre-enlightened past, before almost a third of Canadian farm-operators were women, such an approach might have worked — certainly not in 2013.

Besides confused thinking, what Cosh’s article illustrates is that antiquated, stereotypical, and sexist notions of women still continue to have currency in 2013. Elvgren’s work (his “oeuvre” includes many other similar “on the fence” and “cow-girl” paintings of buxom women caught in embarrassing postures, often with a fetishistic fixation on underwear, or a corresponding lack of underwear) typifies a drooling adolescent view of women as sex objects. Cosh calls such images “saucy” conveying an “innocent flirtatiousness.” At some level, its’ surprising to see such soft-porn visions of women still being promoted in the media, with Cosh dismissing those offended by such stereotypes as “irony phobic socialists” and “literalist doofus'”. Such antediluvian foolishness is astonishing. Cosh writes as if a century of feminism had simply never taken place.

Besides confused thinking, what Cosh’s article illustrates is that antiquated, stereotypical, and sexist notions of women still continue to have currency in 2013. Elvgren’s work (his “oeuvre” includes many other similar “on the fence” and “cow-girl” paintings of buxom women caught in embarrassing postures, often with a fetishistic fixation on underwear, or a corresponding lack of underwear) typifies a drooling adolescent view of women as sex objects. Cosh calls such images “saucy” conveying an “innocent flirtatiousness.” At some level, its’ surprising to see such soft-porn visions of women still being promoted in the media, with Cosh dismissing those offended by such stereotypes as “irony phobic socialists” and “literalist doofus'”. Such antediluvian foolishness is astonishing. Cosh writes as if a century of feminism had simply never taken place.

Fortunately other commentators, those who have been paying attention to the world since Emmeline Pankhurst begin to work for the suffrage of women, have had much more insightful responses. In Canadian Wheat Board ad causes controversy Karl Gotthardt writing for Digital Journal, concludes, “While the ad may be depicted as silly, it certainly seems to have no place in today’s society. From a woman’s point of view it must be deja vous of days gone by. An ad depicting the advantages of marketing through the wheat board, with pros and cons, would have been more appropriate.”

In Canadian Wheat Board turns to ‘sex sells’ mentality with recent ad, Amanda Brodhagen writing for Farms.com says, “I understand that their target audience is for men, but as a woman in the ag-business I am offended by this ad — it’s demeaning to women and it implies that only men are farming in the west these days.” In the Globe and Mail, Shari Graydon says:

“Not surprisingly, the campaign’s message, extolling the sales benefits of the winter wheat pool in very small print, was upstaged by the skin show. Also not surprisingly, genuine cattle ranchers — female and male — objected to the depiction, calling it “stupid”, “sexist” and in “very poor taste” … the truth is that many people intuitively understand the other problems with sexist marketing images: they’re tired clichés, and they insult the intelligence of both men and women.”

Now it is 2013. We no longer live in the Victorian epoch. Cole Porter was right: the days when “a glimpse of stocking was looked on as something shocking” have long since vanished. But again, context is everything. Saucy? Innocent flirtation? Great! Amongst friends, at the bar, at a dance, at the burlesque club: contexts where people play with and poke fun at clichés, and much else besides. But there are contexts where such images are not ironic but are simply juvenile and adolescent — and selling professional grain-marketing services to farmers is one of them.

There are many pressing issues in our world that need addressing. The “Still on the fence?” ad campaign may not be the most consequential of these. However, dispelling “tired cliché’s that insult both men and women” is a not an unimportant objective. Women make up half of the human race. Actions and attitudes that objectify, trivialize, demean, and belittle women as sexual playthings are an impediment to fostering healthy gender relations. Projecting stereotypes on women, rather than treating them on the basis of equality as human beings, is a step backwards — towards the Victorian era rather than away from it. It’s long since time that we understood the difference — and acted accordingly.

Christopher Majka is an ecologist, environmentalist, policy analyst, and writer. He is the director of Natural History Resources and Democracy: Vox Populi.