Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

In an interesting, if not revealing, column in the Globe and Mail (August 29, 2015), economist Todd Hirsch writes that in economics, unlike in philosophy, religion, psychology and other social sciences, uncertainty poses a great challenge. But economists, he claims, are a different breed. We are, he claims, uncomfortable with admitting that the future is unknown; we have problems admitting that “we just don’t know.”

Really?

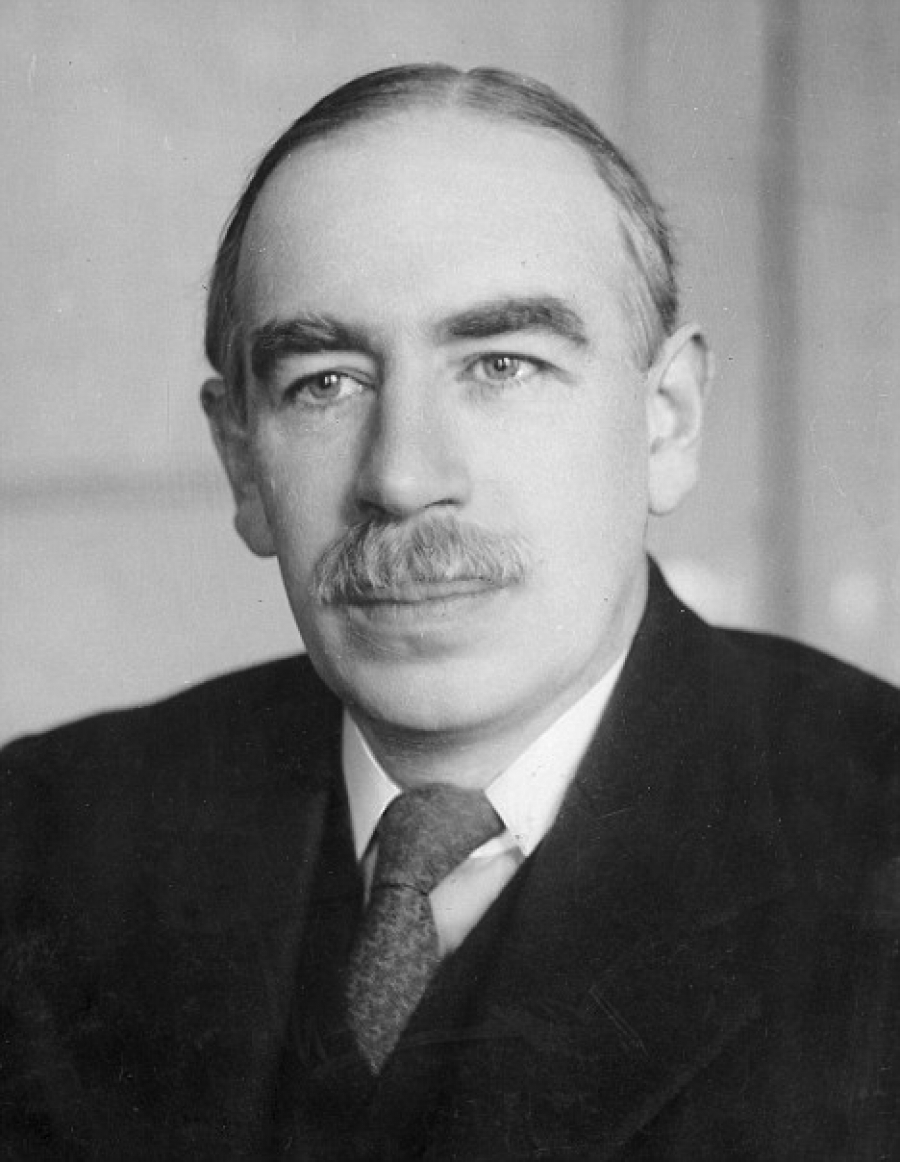

That’s rather odd, since John Maynard Keynes placed uncertainty about the future squarely at the heart of his analysis of capitalism. For Keynes, uncertainty was not the same as risk. In the later case, we know the possible outcomes. In cards, for instance, we know with certainty that I have a four out of 52 chances of getting an ace. That’s not uncertainty, although many economists think it is.

But in economics, it’s true, we have no knowledge of the future. We don’t know what our growth rate will be next year, or indeed next quarter. In the wise words of Keynes, “we simply do not know” what the future holds.

Because the future is unknown and indeed unknowable should not stop us, however, from trying to understand the inherent forces of our economies and devise the proper policies. But we need, as Keynes tells us, a “vigilant observation of the real world” and the proper models.

“Economics is a science of thinking in terms of models joined to the art of choosing models which are relevant to the contemporary world….Good economists are scarce because the gift for using ‘vigilant observation’ to choose good models, although it does not require a highly specialised intellectual technique, appears to be a very rare one.”

Now, Mr. Hirsch is right that most economists are not comfortable with the concept of uncertainty, but that’s only because most economists have been studying the wrong kind of economics all these years. Had they paid more attention to Keynes, it would be a very different world.

This explains in fact why we suffered a huge financial crisis in 2007, by the way. Mainstream economics, the one that is uncomfortable with uncertainty, does not even allow for crises. Unsurprisingly, those economists were not able to predict the 2007 crisis and did not see it coming. This was precisely what Queen Elizabeth asked some British economists: how could anyone not see it coming? It was in fact a total rebuke of the profession. And with reason (by the way, many Keynesians did see the crisis coming, I’m just saying!)

Now, normally, when one approach is so bad at predicting large events like a huge financial crisis, it quietly fades into the shadows and a new approach rises. But not in this case. In fact, the same logic and reasoning that failed to see the signs of the crisis (and there were so many) is still very much dominant in the profession.

But how can we trust this failed intellectual model? How can we still allow it to dictate policy?

Austerity policies, I may add, is at the heart of this failed model. Yet, this has not prevented Mr. Harper and Mr. Mulcair, the dweedledee and dweedledum of Canadian economics (I will let you figure out who is the dee and who is the dumb — I mean dum) of promoting austerity with overzealousness.

There is a worldwide movement, started by students, advocating the “rethinking” of economics. And that is a good thing. We need to bring back the true teaching of Keynes. Of course, when panic sets in, politicians and many economists drum up the old wisdom of the master. But Keynes needs to be part of our thinking not only in times of crises, but in the way we approach everyday economics.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.