When Ontario’s premier Doug Ford and health minister Sylvia Jones announced their plan to increase the role of private facilities for certain surgeries, they sold it as an innovation designed to reduce wait times.

But without meaning to, they revealed some of the grave dangers in their scheme.

The essence of the plan is to allow private facilities – which could be either not-for-profit or for-profit – to do orthopedic surgeries such as hip and knee replacements, and to increase the number of cataract surgeries they do.

Many have expressed doubts about this scheme, including health care workers’ unions, the federal and Ontario New Democrats, and medical organizations such as the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario. Ford dismisses those concerns as “ideological.”

One of the doubters’ major concerns relates to health human resources. They fear private facilities will draw health care professionals away from public hospitals and clinics.

Health Minister Jones’ response on this issue was less than reassuring.

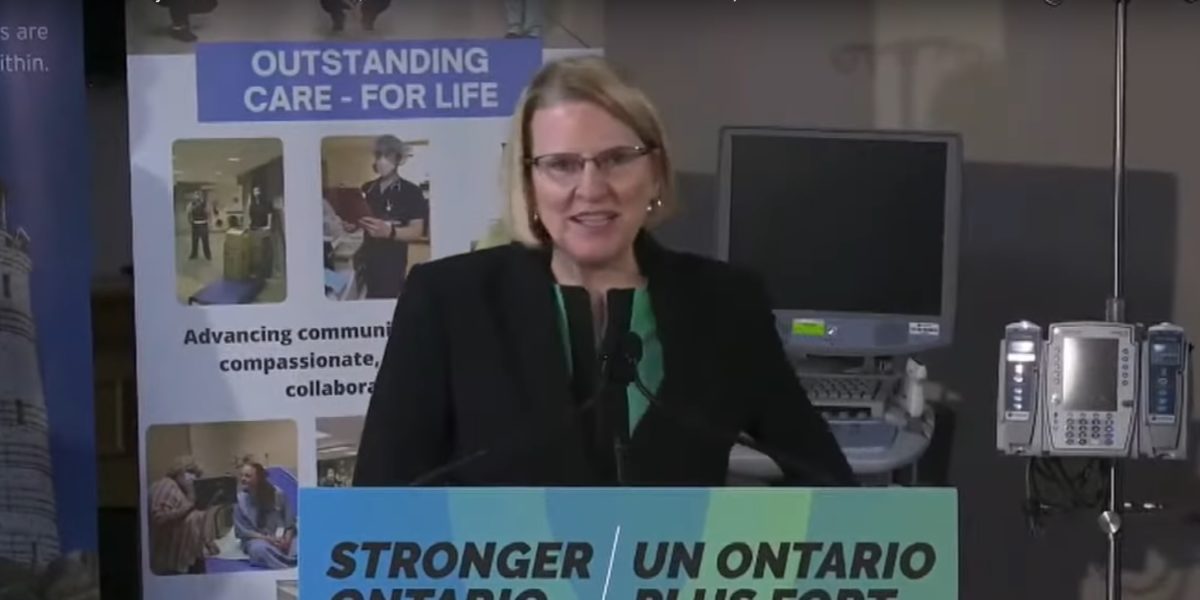

At a news conference announcing the plan on Monday, January 16, the minister tried to obfuscate. She talked about how “complex” the staffing process would be, involving a “lot of different pieces.”

When she finally said something concrete, all Jones could offer was that the government will “ask” private facilities to “report” on how they plan to “staff up”.

The purpose of such reporting will be, somehow, to ensure that the public sector is not hurt by the expansion of for-profit care.

That was pretty much it.

In other words, the government will expect the private facilities to take it upon themselves to prevent the luring of medical professionals from the public system. The foxes will be charged with guarding the henhouse.

Later during the same event, in response to a question about the quality of care in for-profit centres, Ford said it would be the same as in hospitals because the same doctors who perform surgeries in public hospitals would do them in private facilities.

The government would have us believe that the surgeons who now operate exclusively in hospitals would only be devoting their extra time – time when they would not have access to hospital operating rooms – to work in private facilities.

If that were true, there would be no loss to public hospitals, and a gain in capacity for the health care system as a whole.

But is that how it will work, in practice? We have no guarantees, and those who know the health system best have their doubts.

It is hard to imagine that private, for-profit surgery enterprises will not take a competitive approach and make every effort to maximize their business activities – and ergo profits for their investors.

More importantly, a number of Ontario doctors have pointed out that many operating rooms in hospitals now stand empty for long periods. What the system needs, they say, is not more real estate; it is more trained professionals.

Long-term care is not a comforting precedent

As for the standard of care we might expect in the new privately-owned and operated facilities, medical professionals worry the for-profit sector in surgery will replicate the experience of for-profit long-term care.

Just as many private long-term care homes have sacrificed the quality of service for their residents in the interests of their bottom line, so could the surgical private sector seek to maximize profit to the detriment of quality of care.

The health minister offered no more assurance on that issue than she did on human resources.

The fact that the organization which might be responsible for upholding standards – the College – opposes the for-profit model should give all of us, and especially policy-makers, pause.

Yet another bone of contention is the possibility private facilities will try to “upsell” products and services not covered by the public Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) to patients.

That could mean costly lenses for cataract patients, or, eventually, deluxe replacement parts for hips and knees. An ailing person, under pressure to get surgery, is an easy mark for high pressure sales tactics, especially if a private facility offers to accelerate the process on the condition the patient forks over some cash for so-called “enhanced” care.

That’s what two-tiered medicine looks like.

The minister ducked questions on upselling, only saying private facilities would not be allowed to charge patients for services and products covered by OHIP.

Jones ignored the question about pressure tactics to get folks to buy stuff not on OHIP’s list.

Ontario’s premier says his province would only be following the example of several other provinces, such as Alberta, where a large proportion of certain elective surgeries are carried out in non-hospital facilities.

And yet, currently, Ontario’s wait times for such procedures as hip and knee replacements are shorter than they are in provinces that have expanded their surgical for-profit sector.

At the same time, as Doreen Nicoll has pointed out in these pages, Ontario has the lowest health care spending per capita of any province. The province spends $2,000 less per person per year than the average of the other provinces.

The Ford/Jones for-profit plan will do nothing to address the crisis of primary care in Ontario, where over a million people cannot find a family doctor.

And it will not relieve the pressure on emergency departments, which must not only respond to the increased challenge of pandemics, but must act as a de-facto replacement for the missing primary care facilities.

When people need health care and have no other options, they go to emergency.

A case of private sector fundamentalism

Ford tries to portray himself as a pragmatic reformer not motivated by political or so-called ideological bias.

But he shows his own bias when he hauls out the oft-repeated lie that Canada’s health care system is more public than any other country’s, save North Korea and Cuba.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) studies health financing. It reports that about 70 per cent of Canada’s health care is covered by compulsory government schemes. That is well below such major countries as Japan, Germany and France where the figure is 84 or 85 per cent

Ranked by the extent of publicly insured health care, Canada stands in 22nd place. Our rate is below the OECD average of 74 per cent.

Ford’s own motive is, in fact, almost entirely ideological. He is deeply committed to the fanciful notion that the private sector can always do it better.

That was a fashionable notion 40 years ago, in the heyday of Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the U.S. It is less popular these days. The disastrous results of certain privatizations, such as that of British Rail, have taken the bloom off the for-profit rose.

It seems Doug Ford didn’t get the memo.

He’s in a time warp, and is bound and determined to outsource all he can to the private sector.

A recent case in point involves Ontario’s drivers’ testing and employment programs. The Ford government has handed those over to the massive multinational corporation, Serco.

When he made the for-profit surgery announcement Ford talked about having consulted widely. Mostly, however, he seems to have listened to business lobbyists, whose main interest is to find new, low-risk investment opportunities.

One person whose counsel the premier did not appear to seek is Ontario’s Auditor General Bonnie Lysyk.

In 2021 Lysyk’s office issued a report, a value-for-money report on the current state of out-patient surgeries in Ontario.

Among the report’s many critical findings are that the Ontario Health Ministry has no oversight mechanism to prevent patients from being misinformed and being charged inappropriately for publicly funded surgeries.

The report concludes there is widespread abuse on the part of private clinics carrying out cataract operations. Often, the private facilities come close to deceiving patients, telling them they must buy expensive lenses to qualify for surgery that is supposed to be entirely covered by OHIP.

The auditor general’s office hired “mystery shoppers” to call around to private eye clinics to check out their pricing policies and see if they were abiding by government rules.

What they found out was, excuse the pun, eye opening.

To start with they noted that “it is very difficult for the average consumer to obtain complete pricing information.”

That is because almost all clinics that the mystery shoppers contacted “said no pricing lists could be shared without undergoing a consultation.”

A few did share price ranges. The shoppers found that cataract surgeries using specialty lenses would cost the patient anywhere from $450 to almost $5,000 per eye.

More to the point, some clinics said these costly specialty lenses could be mandatory “depending on the surgeon’s assessment.”

The report says such statements are “misleading since all patients have the right to receive publicly funded cataract surgery without paying extra costs for any add-ons.”

When the auditor general can find widespread abuse in the current limited private surgery sector, we can only shudder at what she’s likely to see after the government implements its plan to vastly expand private, for-profit surgeries.