After three years, Canada’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and long COVID is in a dire spot. With struggles in communication and vaccine distribution, experts are concerned about the current response to the global pandemic.

Raywat Deonandan, global health epidemiologist and associate professor at the University of Ottawa, has been a consultant with the private and public sector about COVID. He said while Canada’s COVID response was good early on, it’s since fallen apart.

“Much like the rest of the western world, we are knee-deep in COVID. Even though waves are happening, even though it ebbs and flows, the troughs now are higher than where the peaks were a year or so ago,” he said.

Though Deonandan points to the “miracle” of mRNA vaccines in reducing the mortality rate, he still stressed the deadliness of the disease.

“This is still one of the biggest killers in Canada. Top 10, possibly, and will continue to be so for some time,” he said.

Current domestic vaccine policy is lacking

The COVID response, according to Deonandan, includes five factors: communication, vaccination, testing, treatment and control. He noted that Canada has fallen short in every category except for treatment, which is on par with other nations.

Canadians have uniformly not kept up with COVID-19 vaccines since the initial roll-out. While 80.5 per cent of Canadians completed the initial two-dose round of vaccines when they were made available, in the last six months only 5.7 per cent have received a booster dose, or completed the initial round.

Deonandan said that Canada’s initial vaccine push was remarkable, but the recommendations and work since have failed to keep up. Though there is some debate between experts about what Canada’s low vaccine rate in the past six months means for immunity, he said he believes that the recommendations for the new booster specifically to vulnerable groups are “tepid.”

“We’ve given up on kids under 5 for some strange reason, we should be vaccinating them more. The reason for that is, this is the number 8 killer of children in North America,” he explained. “We forget about that. With vaccination we can just lower that probability.”

“Failure to get boosted probably means the disease spreads more easily but it doesn’t necessarily mean that it has a greater untoward effect on the healthcare system. Unless you count long COVID, in which case it does,” Deonandan said.

Issues in international vaccine policy

In late July, experts from 13 organizations, including doctors, nurses and experts in law and humanitarianism, called for an inquiry into Canada’s “major pandemic failures.” The call was published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ) and laid out in a series of articles that draw attention to the country’s hoarding of vaccines and the virus’ devastation of long term care homes.

Adam Houston is an Adjunct Professor in the Faculty of Law at University of Ottawa, medical policy researcher with Doctors Without Borders Canada and author of one of the BMJ articles focused on Canada’s international vaccine policy. He said Canada failed to learn the right lessons from their early pandemic vaccine approach, pointing to the Foreign Affairs Committee’s recommendations.

“There were some very sensible recommendations in there, a key one being: where drugs and vaccines are developed with a lot of public funding, as was the case in COVID, that public funding should have strings attached,” Houston said. “The government was not very keen on that recommendation at all, and actually wasn’t in agreement with that recommendation from the parliamentary committee.”

Since the release of the papers, Canada waffles on an invitation from South Korea to join the International Vaccine Institute (IVI), an international organization to help poor countries manufacture vaccines. Canada currently has 19 million COVID-19 vaccine doses that are set to expire by the end of 2023.

At least 6.7 million of those are bivalent doses, created to tackle the omicron variant, as well as the original COVID-19 strain.

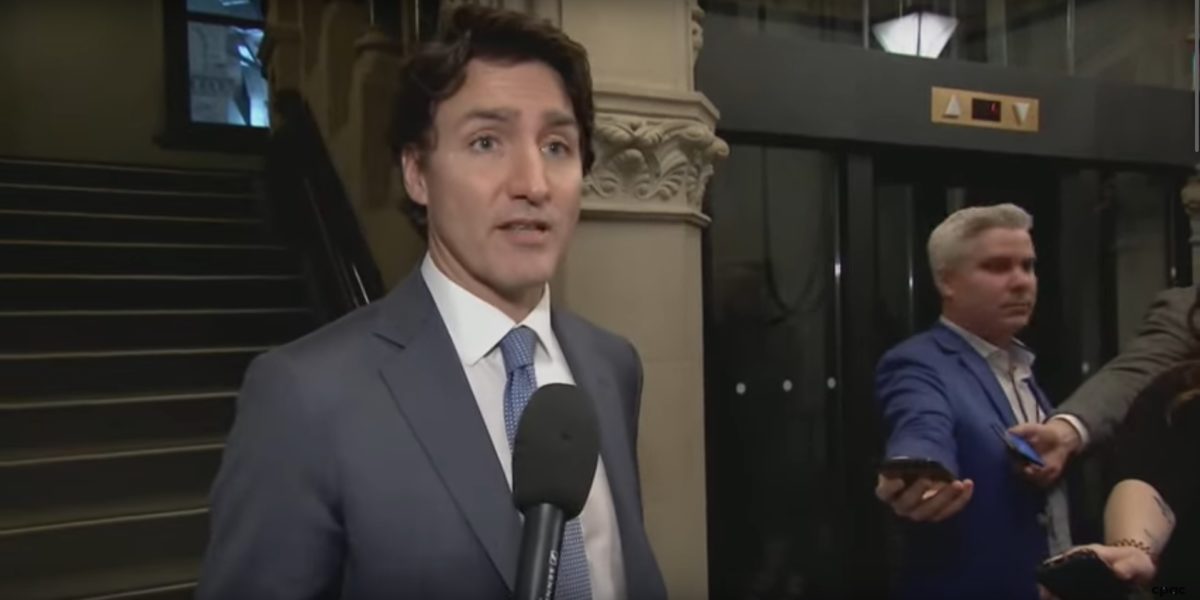

Early on in the pandemic, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised that Canada’s National Research Council would focus its efforts on producing millions of vaccines by the end of 2021. Despite 1.3$ billion being marked for 12 new or expanded biomanufacturing plants to tackle producing vaccines and other treatments, none have been completed

A failure to communicate

However, Deonandan believes that the biggest issue with Canada’s current pandemic response is communication. He said that the government has put the responsibility of appropriate communication on scientists who volunteer information to clarify things for the public.

“Our failure to inoculate the public against imperfect science or bad ideas has been atrocious. We’ve had three years to improve and we’ve gotten worse, not better,” he said, pointing to the speed of misinformation and disinformation that spreads online.

“They had time to put together some kind of task force who communicate well and put them in front of microphones and social media and YouTube to outshout the naysayers,” he explained. “It’s been horrible.”

Houston said he believes the positive response to the call for an inquiry is a good indication of the future, though it may be “a difficult conversation to have.”

“But if we don’t have it, we’re doing this again. I think that is one thing that everybody can agree on,” he said. “Nobody wants to live through 2020 or 2021 again.”

Deonandan said he feels hopeful about the future of weathering the COVID pandemic, citing vaccines absorbed through a nasal spray as a promising future. Though he warned about the politics surrounding the pandemic as the main obstacle to properly tackling the issue.

“I think the future is bright-ish, the great confounder is the political milieu in which we are that gets deeper and darker and murkier,” he said. “Every step of progress we make is beaten down by a political class that wants to convince you otherwise. That’s the great unknown.”