Audrey Macklin, a member of the Faculty of Law at the University of Toronto and a lawyer with the Canadian Refugee Lawyers Association, presented in Halifax, Nova Scotia, on the case before the Federal Court on health care for refugees. The presentation took place at the Weldon School of Law, Dalhousie University earlier this month and the room filled quickly with law students and community members. Ms. Macklin’s presentation was eye opening and shocking for anyone not closely following the changes to the Interim Federal Health Program (IFHP).

IFHP was created in 1957 to provide health care to post-World War II newcomers when universal health care in Canada was not available. Although most health care today is delivered by the provinces, the 1957 Order in Canada (1957-11/848) made the delivery of care to newcomers the responsibility of the federal government likely because there was no universal health care at the time. (The federal government is also responsible for delivering care to aboriginals, inmates and veterans. They used to be responsible for RCMP but the Harper government cut funding to that program a few years ago and RCMP care is now the responsibility of the provinces.)

Previous to 2012, all newcomers to Canada were treated equally in regards to their care. Unlike the federal Conservatives’ claim that refugees were receiving “gold-plated” health care, refugees were only able to access a similar basket of services as low-income Canadians.

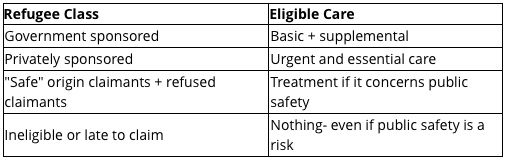

Since 2012, refugees have been split into several classes that determine their access to care.

The chart above is a very simple version of a much more complicated list of classifications and eligible services given to the offices of health practitioners. The document clinics received was so confusing that many health-care clinics simply refused treatment to refugees regardless of their classification.

Macklin broke down what these changes meant in one particularly powerful example. An asthmatic refugee child who is sponsored by the Harper government will receive medical attention and asthma medication when they enter the country. A Roma child from Hungary (deemed a ‘safe’ country) who is hit by a vehicle in Canada is not eligible for care — even emergency treatment.

Macklin further debunks the Harper government’s justifications for the changes to the IFHP by addressing the government’s claims that changes to IFHP saves Canadian taxpayers money. The Harper government claims it has saved $600 million since last year. But what’s really happening is $600 million has been taken out of the federal government’s budget and it’s been jettisoned onto the provinces’ and territories’ books. So either way taxpayers are paying. But there’s reason to also believe that these changes are costing more money. With primary services denied to many refugees, people are waiting until conditions worsen to access services. This often leaves them to access services when in crisis at the Emergency Department (ED) — the most expensive way to access services in Canada. A non-sponsored refugee will leave the ED with a bill that they may not be able to pay. This charge will go to the hospital’s bad debt — which then needs to be paid by the province. By then, a health concern that may have been addressed with primary care is now costing much more.

But I don’t believe that the discussion of treating newcomers to Canada should be centred on costs to “taxpayers” (remember that refugees also pay taxes), but rather on how we ensure everyone has access to the services we need.

According to Canadian Doctors for Refugee Health Care, the Conservatives have been claiming that refugees come to Canada to exploit our health-care system. But Macklin made the excellent point that refugees use one-tenth of the health care that Canadians use. You’d think they’d make better use of the system if they travelled all the way to Canada to take advantage of it.

If all of this wasn’t bad enough, it’s important to note that Canada is the only wealthy, industrialized country in the world that restricts this care. Even the U.S., who we often think of as having fewer caring policies than Canada, offers care to pregnant women and children regardless of their country of origin.

Changes to the IFHP is another way Canada has become a less caring country. It’s another policy of the federal Conservatives that is extremely out of touch with the country Canadians are trying to build. The Council of Canadians offers our support and solidarity to Canadian Doctors for Refugee Care, the Canadian Association of Refugee Lawyers, and the brave refugees who are standing up for their rights and for the rights of future newcomers.