After 10 days, Obert Mandondo says he is finally feeling the effects of his hunger strike.

“I was healthy until yesterday. Usually in the mornings I have a lot of energy, but today is a different story,” he says. “I’m starting to feel very weak.”

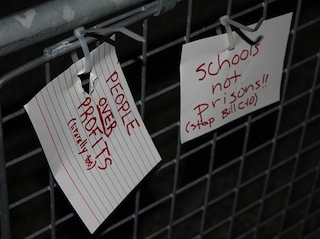

That hasn’t stopped the Ottawa blogger and activist from continuing to work towards his demands. Four of his five demands involve the appeal of Bill C-10, the omnibus crime bill.

He is also campaigning for the resignation of former Ottawa Police Chief-turned-Senator Vern White, for the police involvement in the Occupy Ottawa eviction. Madondo says his back and arm were injured during the protest.

Bill C-10 is composed of a handful of smaller bills that didn’t pass during the Conservative minority. Ironically dubbed the Safe Streets and Communities Act at a time when Canadian streets are safer than ever, the bill has many aspects to oppose.

It has been widely criticized for enforcing mandatory minimum sentences on certain crimes and its bottom-line cost to taxpayers. Madondo says he agrees, adding that the bill attacks already vulnerable groups: young offenders, people of colour and Canadians charged with crimes overseas.

He says handing out longer and more frequent prison sentences will not actually deal with the roots of crime such as education, poverty and oppression — it merely follows a certain ideology.

“This bill is a tool for the Conservatives to push their right-wing world view on Canada, a worldview that’s based on punishment,” he says.

Madondo says he followed the bill since first reading but was shocked at how it was passed. He echoes criticisms that experts, MPs and due process were ignored, and says the Conservatives have created an accusatory political climate that was embodied by the bill, where anyone opposed to the motion was labelled an “enemy of the state.”

“We had a kind of terror that went on during the making of this bill,” he says. “I was outraged by the lack of adherence to the process in Parliament: that got me to say I need to do something.”

He says the bill is not just contradictory to Canadian opinion, but also to Canadian values. He decided on a hunger strike as a non-violent form of protest to reignite discussion about the bill.

“It speaks to this Canadian value of compassion,” he says. “This is like the last stand against this bill.”

Hunger strikes may seem rare but they are used in Canada. A week before Madondo took action, a Fredericton man also went on a hunger strike to raise awareness about hunger in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

While some protesters set a timeline for their strikes, others like Madondo’s go on indefinitely. A raw-milk crusader ended his two-month-long hunger strike after a meeting with the Ontario premier in November. A veteran advocated for an investigation into the health of soldiers possibly contaminated by uranium while serving in Bosnia. His four-day hunger strike ended successfully, also in November.

Unfortunately, these protests aren’t always effective. Istvan Marton, a British Columbia man trying to legalize marijuana, died of a heart attack while on his hunger strike in 2011.

How long someone can survive while on a hunger strike depends on how much they restrict. Madondo is still drinking juice and water throughout his protest and remains optimistic. He hopes his Facebook and Twitter updates will help keep attention on his cause.

But he says he is willing to do whatever it takes to fight the bill.

“If it means engage in this action to the last breath I will do it because this is how important it is for me to stand up and fight for those that are going to be victims of this Act.”

On March 27, 2012, march with Obert Madondo to deliver his demands to Parliament Hill.

Steffanie Pinch rocks rabble’s Activist Toolkit internship. A journalism major in her fourth year with a minor in gender studies, she has been covering and participating in protests throughout her time at Carleton University. She can be found hanging around Ottawa, drinking fair trade coffee and making socially conscious documentaries.