Late last week, the Ross River Dena First Nation learned that the Supreme Court of Canada would not hear the Yukon Government’s appeal of an earlier decision that sharply rebuked the territory’s free entry mineral staking regime. This means the earlier decision of the Yukon Court of Appeal stands.

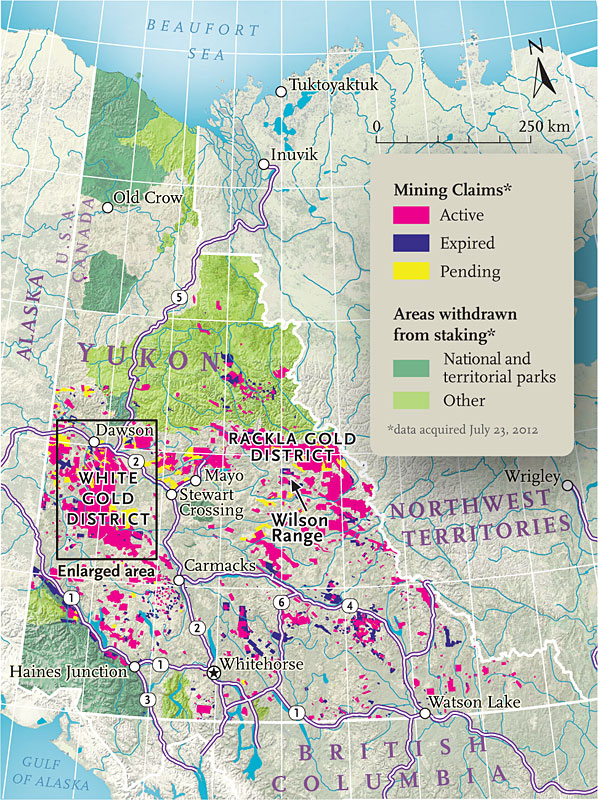

Ross River took the government to court over its practice of allowing mineral claims to be staked and early exploration activities to occur on the First Nation’s traditional lands without prior consultation or accommodation of their Aboriginal rights and title. (Yukon Conservation Society has a great animated graphic of claim staking in the Yukon.) The judge hearing the case for the Yukon Court of Appeal agreed and found in favour of Ross River requiring the Yukon government to consult and accommodate Ross River’s Aboriginal rights and title before claim staking and before any exploration activities occur.

While the need to consult on later stage exploration activities is fairly well established in Canadian case law (though not respected in all jurisdictions) this is the first time the courts have clearly indicated the need to have consultation BEFORE a prospector or mining company stakes a property. The decision is an important recognition that claim staking is not free of impacts to Aboriginal title as it establishes a third-party interest that can greatly encumber future decisions about the land.

The Yukon government argued that they did not have a duty to consult because they were not actively making decisions about claim staking or early exploration. The Court of Appeal Judge didn’t buy that, stating:

“The duty to consult exists to ensure that the Crown does not manage its resources in a manner that ignores Aboriginal claims. It is a mechanism by which the claims of First Nations can be reconciled with the Crown’s right to manage resources. Statutory regimes that do not allow for consultation and fail to provide any other equally effective means to acknowledge and accommodate Aboriginal claims are defective and cannot be allowed to subsist.”

As is expected there has been hyperbolic statements from the Yukon Prospectors Association about the sky falling in on the industry. CBC quoted the Association’s president saying that:

Anything that detracts from the Yukon’s otherwise good reputation as a place to invest in mineral exploration will make it tougher for us at the bottom of the food chain to defend the properties we’re exploring.

The Prospectors Association fails to recognize that persistent conflict and lack of clarity about the process for reconciling Aboriginal rights and title are as likely (if not more so) to scare away investors, as are extra steps involved in staking a claim, early consultation or the removal of some areas from access to staking in order to respect Aboriginal rights and title.

The need to address Aboriginal title before claim staking is likely to have implications across Canada as there is no jurisdiction that has a system in place to do so. Some parts of some provinces and territories may be compliant with the Ross River decision on claim staking if a land use plan identifying areas open for staking has been agreed to with the Aboriginal peoples of the area. There are, however, relatively few areas where this is the case.

The requirement to consult before any exploration activities occur is likely to require modifications to most existing consultation processes. A possible exception is Ontario, where new regulations require consultation by mining companies before they file work plans or request exploration permits.

Provincial, territorial and the federal governments will likely argue that the decision doesn’t apply to areas with historic or modern treaties as their interpretation of the treaties is that they extinguish all prior Aboriginal rights and title. Aboriginal signatories and some legal experts disagree with the Crown’s interpretation of the treaties and will likely push to apply the decision more broadly.

Areas without historic or modern land-based treaties include most of B.C., parts of Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland and Labrador, and all of the Maritimes. In theory, there should be few barriers to applying the full scope of the Ross River decision to these areas.

The Yukon government was mandated by the court to respond to its decision by the end of the year but their response so far indicates they do not intend to apply the decision outside of the Ross River area. Whether other territorial and provincial governments see the writing on the wall remains to be seen. If past history is any indication, it may take more lawsuits to ensure they live up to the standard established by the Ross River case — a pattern that has caught the attention of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. The Committee’s 2012 report on Canada expressed concern “that Aboriginal peoples incur heavy financial expenditures in litigation to resolve land disputes with the State party owing to rigidly adversarial positions taken by the State party in such disputes.”

NOTE: The full Ross River vs. Yukon Court of Appeal decision is quite readable and available here. A few select quotes are included below.

[43] I fully understand that the open entry system continued under the Quartz Mining Act* has considerable value in maintaining a viable mining industry and encouraging prospecting. I also acknowledge that there is a long tradition of acquiring mineral claims by staking, and that the system is important both historically and economically to Yukon. It must, however, be modified in order for the Crown to act in accordance with its constitutional duties.

[44] The potential impact of mining claims on Aboriginal title and rights is such that mere notice cannot suffice as the sole mechanism of consultation. A more elaborate system must be grafted onto the regime set out in the Quartz Mining Act. In particular, the regime must allow for an appropriate level of consultation before Aboriginal claims are adversely affected.

[51] At least where Class 1 exploration activities will have serious or long-lasting adverse effects on claimed Aboriginal rights, the Crown must be in a position to engage in consultations with First Nations before the activities are allowed to take place. The affected First Nation must be provided with notice of the proposed activities and, where appropriate, an opportunity to consult prior to the activity taking place. The Crown must ensure that it maintains the ability to prevent or regulate activities where it is appropriate to do so.

Image: Map of Yukon mineral claims, Canadian Geographic