2023 marks the eighth year since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released a list of 94 Calls to Action, but the Liberal government is making progress on those Calls to Action at a snail’s pace.

The six volume Final Report and Calls to Action, published in December 2015, painted a roadmap to reconciliation, one that’s been little more then lip service.

Speaking of lip service, 2022 saw the papal apology during a visit to Canada, recognizing the Catholic Church’s leadership in the implementation and abuses of the residential school system.

A December 2022 report by the Yellowhead Institute concluded there remains a “tremendous amount” to be done from health, education, and child welfare to justice and Indigenous languages to advance reconciliation.

The 49-page report noted that 13 Calls have been completed. At this rate, it will take 42 years, or until 2065, to complete all the Calls to Action.

When the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released their findings in 2015, they characterized the legacy of the residential school system as “cultural genocide,” a term that became the subject of scrutiny by politicians and media alike.

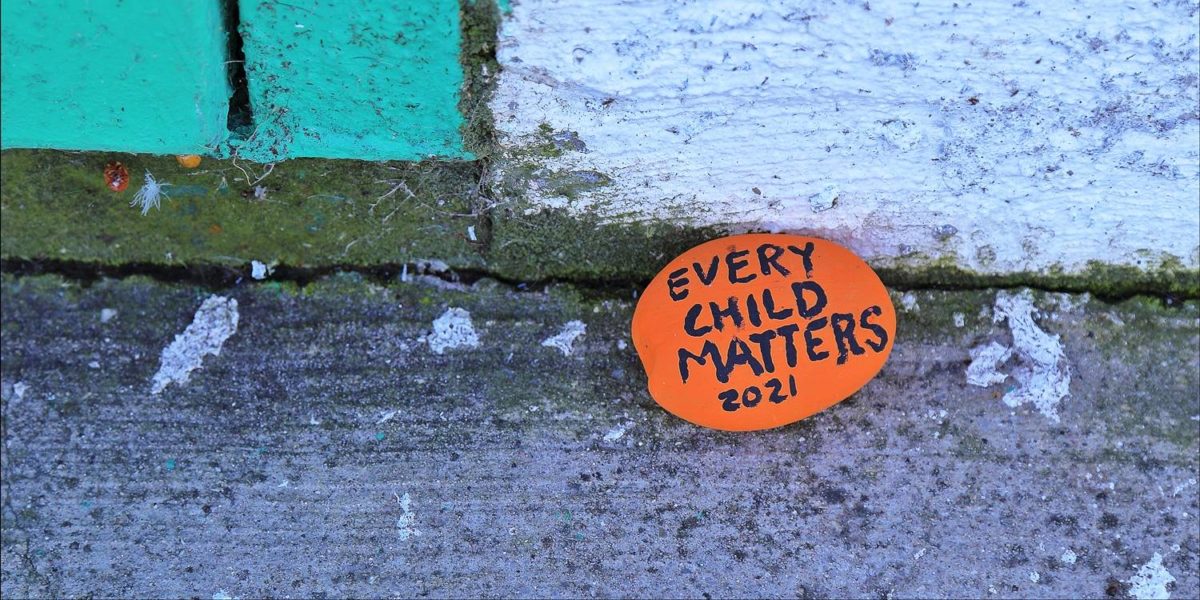

But by October 2022, in the wake of the discovery of unmarked graves of Indigenous children on sites of former residential schools, a milestone was reached in the House of Commons when NDP MP Leah Gazan moved for the federal government to recognize the history of Canada’s Indian Residential Schools as genocide. The motion received unanimous consent.

September 30 is now recognized as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

But the glacial pace with which the government is approaching these Calls is sending a message to Indigenous communities that it’s not a priority.

A closer look at the 94 Calls to Action

There are two categories of Calls to Action and it’s clear which one has become the favourite of the federal government.

The first 42 are known as Legacy Calls to Action, which address inequalities in child welfare, education, health, culture and language, and justice. The report notes many of the Legacy Calls to Action “aim to end injustices that Indigenous peoples are still experiencing.”

The rest are known as Reconciliation Calls to Action, made up mostly of inclusion and education efforts.

Report contributors Dr. Eva Jewell and Dr. Ian Mosby called out the failure of the federal government to implement Calls to Action that help further other Calls.

“Part of the answer, of course, is that the data is often at odds with the government’s own narrative of progress,” Jewell and Mosby write.

Call to Action 2 is just one example. It requires all levels of government to make public data related to Indigenous children in the child welfare system through an annual report.

“This lack of transparency makes it difficult, if not impossible, to take the government’s own claims regarding their progress on the Calls to Action seriously,” they add.

Without the dissemination of that critical information, Jewell and Mosby conclude, there won’t be enough data to accurately measure whether many of these Legacy Calls to Action have been completed.

The first, Call to Action 67, saw the Canadian Museums Association open a national review of museum policies and best practices in order to determine their compliance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Meanwhile, Call to Action 70 urged the Canadian Association of Archivists to undertake a similar national review, as well releasing a reconciliation framework for Canadian archives.

In addition to the two completed Calls to Action, 2022 also saw the introduction of Bill C-29, The National Council for Reconciliation Act. If the bill receives royal assent, it could achieve Call to Action 53.

The Council would be mandated to monitor, evaluate, and report every year on the status of each of the Calls to Action, providing greater oversight and accountability into their completion. It would, according to the report, have the potential to publish data on, and therefore achieve Calls 2, 9, 19, and 30.

The first sentence of the book of reconciliation

AFN National Chief RoseAnne Archibald has said that, “if we were in a chapter of a book on reconciliation — we are, today, on the first sentence of that book.”

Cindy Blackstock agrees. Blackstock is a professor at McGill University’s School of Social Work and serves as the Executive Director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society.

“The fact that Canada has failed, yet again, to complete any of the Child Welfare Calls to Action in 2022 should give us pause,” Blackstock wrote in the report.

Blackstock pointed out that there are currently more Indigenous children in the child welfare system than at the height of the residential school system.

“Instead of being dedicated to reconciliation, Canada’s behaviour shows that they are resisting substantive change, preferring those Calls to Action they can easily perform and that makes them look good,” Blackstock said.