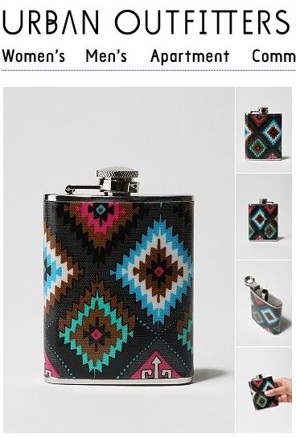

Although the specific legal principles involved may differ, use of the terms icewine, Roquefort and Navajo all have something in common. They tell you something about what you are buying, and in this case, the Navajo Nation wants to ensure that consumers are not associating the term ‘Navajo’ with “random south-west inspired hipster fashion.”

You may have heard of the recent lawsuit launched by the Navajo Nation against clothing giant Urban Outfitters. I’d like to provide some more legal context. Please bear with me.

Icewine is pressed from grapes that freeze on the vine, and is an incredibly sweet and expensive dessert wine. Canada is the largest producer of authentic icewine in the world. A 375ml bottle will cost you about $45 Canadian here, but can go up to a couple of hundred smackarooneys on foreign markets.

Fake icewine started popping up fairly early both here in Canada and abroad. To deal with this, B.C., Ontario and Nova Scotia set up special provincial legislation under the Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) to regulate the production and quality of icewines produced in those regions.

The VQA is a wine appellation system, meaning that certain terms applied to wines can only be used if the product meets specific criteria. It is illegal to use those terms otherwise.

Appellation laws have existed in many countries for centuries. Champagne originally enjoyed widespread legal appellation protection under the Treaty of Madrid, 1891 which stated that only sparkling wines produced in a specific area of France could be called ‘champagne.’ This has been affirmed in various treaties and laws since.

Alcoholic beverages are not the only products to enjoy such legal protections. Cheeses are another fine example, using something called a Geographical Indication (GI) to describe where the product comes from, guaranteeing everything from quality to specific production methods.

In Europe, these kinds of labels have to do more with where the product is made. Thus when you buy Roquefort cheese, you know it comes from a specific region in France.

The United States takes a different approach to some of these issues, where certain terms or names are considered a form of intellectual property, specifically a trademark.

Brian Lewis, an attorney with the Navajo Nation Department of Justice, says the group wants Urban Outfitters to “stop misappropriating the ‘Navajo’ name and trademark.”

That’s right. The Navajo Nation has trademark ownership of the name ‘Navajo,’ just like Urban Outfitters owns the trademark to its name. The Navajo Nation has the legal right to stop people from using its trademark to describe products that have not been approved.

Urban Outfitters responded with this back in October:

“Like many other fashion brands, we interpret trends and will continue to do so for years to come […] The Native American-inspired trend and specifically the term ‘Navajo’ have been cycling through fashion, fine art and design for the last few years.”

This is true, but it won’t save Urban Outfitters from being held accountable for their trademark infringement. “Everyone else does it” is not a legal defence.

But it could become one if the Navajo Nation does not enforce its rights.

In trademark law, there is a concept called genericisation, where once a trademark becomes overused, it can expire. A famous example involves the company, Xerox. Its trademark was threatened when people began to use the term ‘xerox’ in the place of ‘photocopy.’ Only an aggressive ad campaign saved Xerox from joining the ranks of trademarks lost to colloquial use.

There is also a statute in the United States called the Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990. There is no such equivalent in Canada. This law states that no person who is not an enrolled member of a federally or state recognised tribe can produce items labelled ‘Native American’ or ‘Indian.’ In addition, members of one tribe cannot pass their items off as coming from a different tribe, so if your goods are labelled ‘Hopi,’ you’d better be a member or a certified artisan of the the Hopi.

If you think that this case is frivolous or interferes with ‘freedom of expression’ and so forth, please ensure that you are not singling out indigenous peoples with this criticism. If you take issue with intellectual property law, with appellation statutes or geographical indication laws, then your concerns are not limited to us and need not focus on this case.

If however you just want to be able to call your stuff ‘Native American’ or ‘Navajo’ with no consequences, I’m afraid you’ve got some explaining to do.

A more detailed version of this article was published on the author’s blog, âpihtawikosisân.