In light of the recent tragic incident involving the death of 10 migrant workers in Southern Ontario, I felt it was finally time to take the wraps off of a journal I kept during a two-week trip in early 2004 to investigate the conditions of undocumented Chinese migrant farm workers. I hope this can help shed light on the kinds of conditions faced every day by the people who tend, pick and process the food we eat.

This is the seventh in a series. See here for the first entry.

The families of the deceased and injured are very much in need of financial and logistical support. As such, a fund has been set up so that donations may be made to them. At the same time, a sustained, organized, well-informed effort is needed to prevent similar tragedies. Please consider supporting groups like Justice 4 Migrant Workers and joining migrant farm worker advocates in calling for greater accountability and compensation.

—

With two-thirds of our group having returned to Toronto, things are irritatingly and eerily quiet in the morning. Eight or nine more workers are to arrive tomorrow. I wonder how to greet them: how should we warn them to expect instability here?

The eldest of my usual workmates isn’t working today; his back isn’t doing well. The rest of us return to the usual greenhouse where the cucumbers continue to grow quickly, particularly for mid-January. The owner offers us rent-free accommodation if we choose to stay in his facilities, but I give it only passing consideration. The concrete and steel bathroom facilities we’ve grown accustomed to may be cold and industrial, but the semi-finished bathroom facilities here, assembled from odds and ends, leave much to be desired.

Throughout the day I reflect on my position as an intermediary between the contractor and my colleagues. It’s disorienting. It both derives from and reinforces the power and privilege I disproportionately possess. Without any formal selection procedure or my active seeking of the role, I’ve fallen upon it. The others look to me to help determine their employment and living circumstances. I can’t help but feel frustrated by this unsolicited responsibility, which conflicts with my initial goals of being a non-interfering observer and covert ESL teacher. I also believe my work should be guided by my colleagues, though, so I carry on in the role as best I can.

During the day, I have a conversation with one of the Canadian workers also employed here. He asks where I live. When I reply that I’m “in between places” at the moment, he takes it to mean that I’m homeless and tells me about the times in his life he’s been homeless himself. I almost start to explain that I’m not quite homeless, but sense that he just needs to tell someone a bit about himself, so I stop myself and listen to his story as we work our way down some rows, he faster than I.

When we return from work, the building housing our quarters reeks with smoke. A white haze fills the air. There’s no indication of its nature or source, so I opt to take refuge in our sleeping quarters until it disperses somewhat. Some of my colleagues, however, ignore the haze and go about their usual business in the kitchen, which opens directly into the smoky warehouse.

After dinner, the pressure to move to and stay in the cucumber greenhouse resumes. Although only one greenhouse so far has shown significant concern about workers carrying plant diseases between facilities, the contractor claims it’s becoming more important that we not be mobile between greenhouses to prevent transporting diseases between greenhouses. He seems confident that this will force us to move.

The owner of the greenhouse we’re living in visits our kitchen. He tells our contractor that we have to move. He speaks with finality, reiterating the plant disease concerns. Not content to accept the fiat, though, my workmates and I immediately start to strategize. We decide to wait until morning and see what happens. Our leverage will grow overnight: by morning the contractor will be in urgent need of our services. Furthermore, we fully expect the contractor to request more than what they truly need, so if we wait until morning, then ignore what they’ve asked for, there is a decent chance the overnight gap will cause them to forget the urgency of their demands.

So it is that we manage to depart for our next workday at the cucumber greenhouse without our bags. Later in the day, noticing our resolve to remain housed at the larger greenhouse, the owner of the cucumber greenhouse calls the owner of our host greenhouse to negotiate a way for us to continue living there. They’re part of the same large family that runs several greenhouses in the area (most of the tomato business is dominated by similarly massive extended-family operations). We’re told we have the OK, and remain lodged at our greenhouse of choice.

Epilogue and final words

The events of this journal happened in 2004, over eight years ago. It has taken me this long to publish these words in part because I was concerned that publicly exposing these contractors might cause them to attempt some kind of reprisal. Enough time has passed now that that fear has faded, but so has some of my recollection. The articles to date have been culled from emails I sent to a trusted network shortly after the events occurred.

It’s at this point that my journals begin to run dry, and I must try to piece together the last fragments of recollection that I have of the events leading up to my departure from the greenhouse. The journal perhaps ran dry because of an odd incident that happened one evening in the time between dinner, haggling over the day’s wages and living conditions, and bedtime. I was reclined in bed, either reading or taking notes on the day’s events, and the contractor’s multilingual translator and negotiator approached my bunk. I looked up to see what he wanted, but he had nothing to say. He simply looked at me, making eye contact through his large, gold-rimmed glasses for several awkward seconds before throwing his head back and laughing for a few more awkward seconds, turning, and leaving the room. Whatever his intentions, he succeeded in making me act much more furtively in my record keeping.

There was, of course, record-keeping they would have expected any of us to do, and so thanks to the records I had to keep of each day’s location and hours of work, I know that some of us continued working at the cucumber greenhouse for a few days. We then spent the last two days of that second week at the larger greenhouse where we had been living. At every greenhouse, I tried to get an idea of how much money the contractor was skimming off the $7 hourly rate we earned. I learned that some greenhouses paid as much as $12.50 an hour for our work — nearly an 80 per cent mark-up.

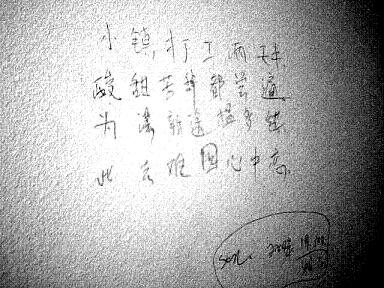

At one point I noticed, and took a picture of, some graffiti written in Chinese on one of the greenhouses’ bathroom stalls. Signed “SON, 2004,” it reads, translated: “Worked in this small town two and a half days. Tasted sour, sweet, bitter, and heat. Looking to discover a bit of fortune. Only to discover it’s not here.”

Aylwin Lo (@aylwinlo) was a Labourer-Teacher with Frontier College in 2003, and an Into The Fields intern with Student Action with Farmworkers in 2006. He has volunteered with Justice for Migrant Workers and currently resides in Toronto, where he integrates varying combinations of technology, graphic design, and politics.