“Rise Up for a Just Recovery”; a Labour Day slogan this year that must include housing.

Labour Day has come and gone. In this federal election, perhaps more importantly, after this election, the solidarity of workers and their unions with housing advocates will be essential to end Canada’s housing and homelessness crisis.

The anti-poverty advocacy groups I have been part of depended on unions.

I once received a five-figure cheque for speaking at a Canadian Auto Workers (CAW — now Unifor) assembly. It wasn’t actually for me; it was for the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC) and when Buzz Hargrove presented it to me, I teared up. We were such a poor organization. Most grassroots activist groups are.

The donation did not just come out of the blue. It was the result of solidarity.

My long-time colleague Beric German and I had taken the Auto Workers’ Buzz Hargrove and Sam Gindin on a disaster tour, showing them the ugliness of inner-city poverty and homelessness. Many CAW staff including Peggy Nash, Jim Stanford, Steve Watson and Herman Rosenfeld integrated housing and homelessness issues into their work in the union.

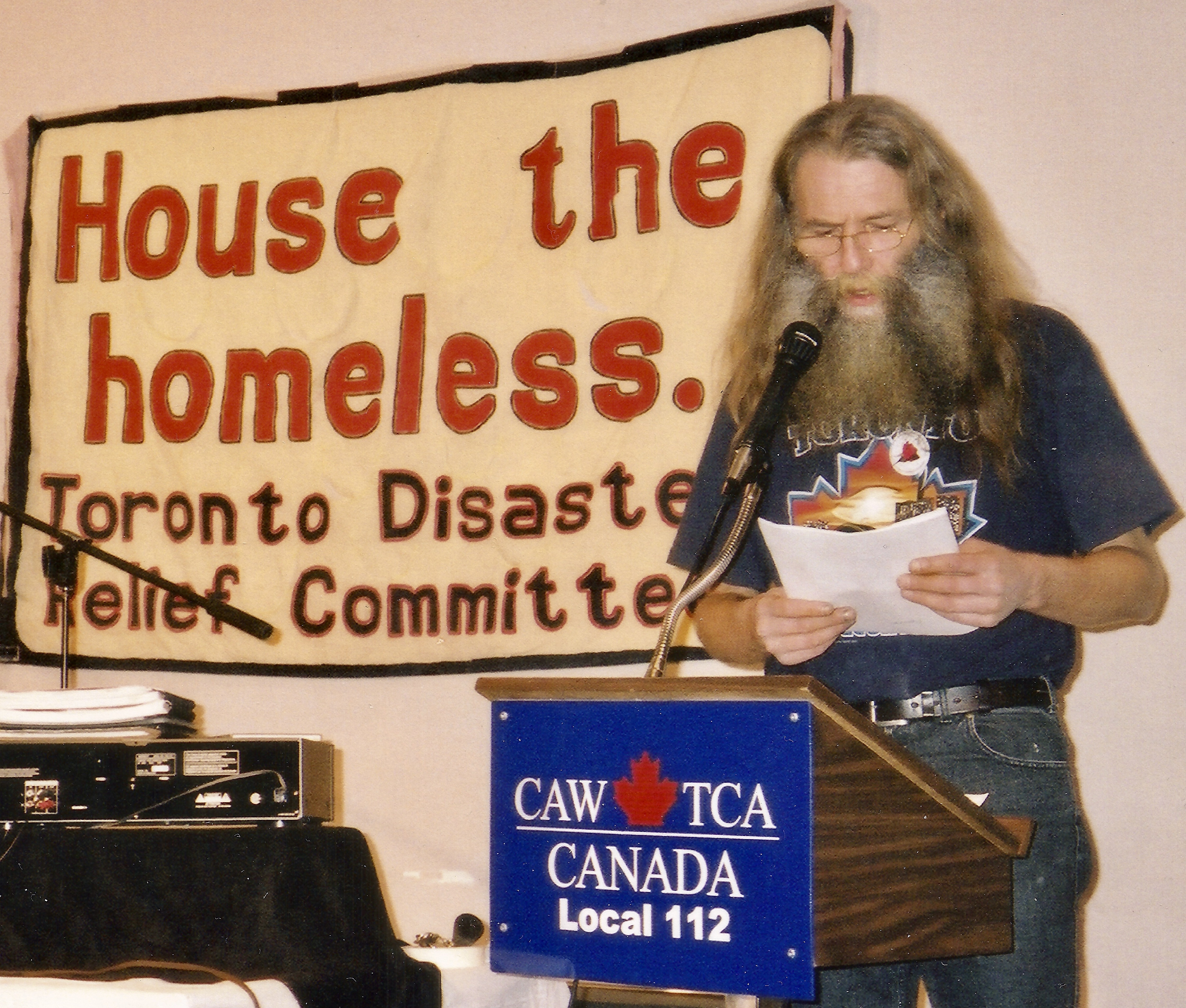

Advocacy at CAW locals grew out of our joint sessions at the CAW Port Elgin education site. This included the work of a Local 112 member Chris Bognat who created a book Homelessness: A Message for Working Canadians (out of print) for union education and to fundraise for TDRC.

Many CAW locals fundraised and donated to us.

We spoke at their rallies; they spoke at our rallies. TDRC events nearly always had union flags flying high.

CAW helped to pay for six portable toilets at Tent City and they included many of the Tent City residents at their events. When Tent City was brutally evicted, union members showed up. It’s important to note those residents won a historic rent supplement program to help them afford housing.

These efforts spearheaded multiple years of union support for both TDRC and the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty.

In her memoir Waking Up in the Men’s Room (Between the Lines 1998), Catherine Macleod describes the awakening union members had to many social justice issues including housing.

“It became clear that if so many people were losing jobs, the unemployment insurance program couldn’t be cut. If the women at Freuhauf (a former CAW plant in Mississauga that was closed in 1989) were to be retrained, more childcare was needed. If working-class families were going to have the strength to deal with the financial pressures, the public health system was as important as ever. If workers were losing their homes, more affordable housing was essential.”

Auto-industry workers and their families who had lost their job in the wake of the damage of Free Trade participated in a film I produced with Laura Sky. Home Safe Toronto focused on several auto workers and their families. Some of them had become homeless. Some were on the brink. This film, featuring former CAW worker Jim McDowell, among others, remains an important education tool for unions.

Flash forward to today.

My own survey of a dozen national unions’ websites campaigns and issues buttons came up with nothing on housing and homelessness. One exception was the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions, which hosted a Facebook chat between their president Linda Silas, myself and Tracy Zambory, president of the Saskatchewan Union of Nurses.

This neglect of a core building block of social justice is worrisome given the ample evidence of an acute housing shortage, housing unaffordability and a homelessness crisis that has always affected workers. Dri, a Tent City resident, (pictured here) had once been a labourer building Toronto’s SkyDome (now named the Rogers Centre).

This void reflects the reality of many of my colleagues on the ground. I’m sure there are many reasons for the inattention, including declining union membership.

However, the obvious failure of neoliberal government policies — including the federal government’s National Housing Strategy — should be a call to mobilize. The obvious suffering, trauma, and literal disaster conditions on the ground should generate a response, as it once did at Toronto’s Tent City. Shamefully, in multiple Canadian cities it has been unionized workers tasked to carry out encampment evictions.

As long-time anti-poverty organizer John Clark remarked:

“In these times of pandemic triggered social crisis, unions have to rethink their concept of working-class solidarity so as to leave no one behind. Unionized municipal workers can’t be used to help drive homeless people seeking shelter from parks. When cops are sent to break up homeless camps, we need union members to rally in support as surely as they would defend a picket line during a strike.”

No matter the outcome of the federal election, a solidarity movement between unions and activist groups needs to be refreshed.

Our future depends on trade union solidarity. As my colleague Beric German notes:

“Not all people in the trade union movement are able to afford their housing. The essence of the trade union movement is to not just work for oneself but for all. Our society relies on the strength and commitment of trade unions and other social organizations. Their solidarity is crucial to all of us.”

This line from Gordon Lightfoot’s Canadian Railway Trilogy should be our call to arms:

“We got to get on our way ’cause we’re movin’ too slow

Get on our way ’cause we’re movin’ too slow.”

Cathy Crowe is a street nurse, author and filmmaker who works nationally and locally on health and social justice issues.

Image: Cathy Crowe/Provided