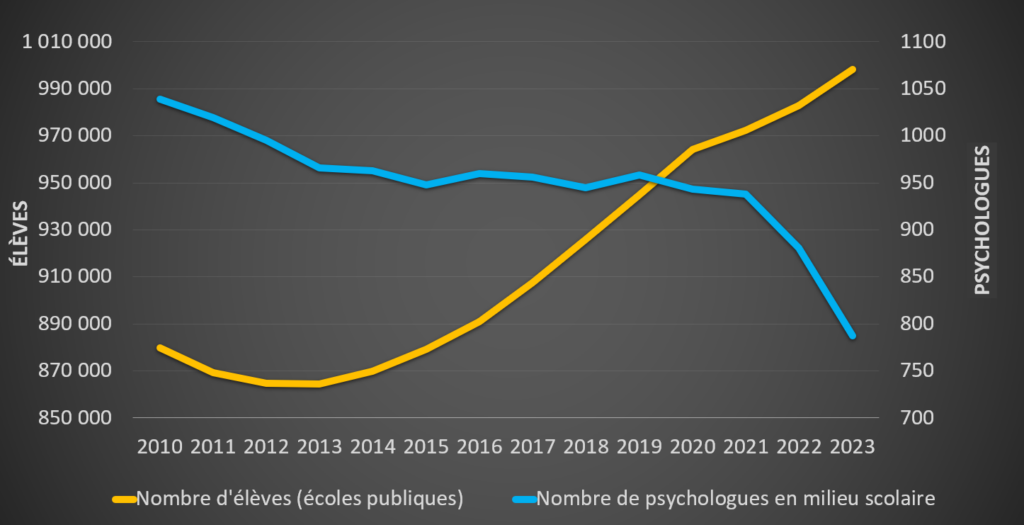

For more than a decade, the public education system in Quebec has seen a dramatic decrease in the number of psychologists available to students, says data published by the Ordre des psychologues du Québec.

Mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and eating disorders, among elementary and highschool students have increased, sounding alarm bells for psychologists and teachers alike. Some are arguing that the creation of a union solely for public sector psychologists is the only avenue to creating meaningful and long-lasting change for psychologists and students alike.

Poor working conditions, coupled with low wages and a general lack of autonomy are driving the few psychologists in the public sector towards the private, leaving those that remain spent and stretched to the limit.

Suicide and suicidal ideation, anxiety, depression, and other mental health conditions among elementary and high school students have been on the rise even as the COVID-19 pandemic has subsided, with a 42 per cent increase over the past year. But, with only one psychologist per approximately 1,300 students, following-up on initial diagnoses is difficult.

There are currently about one million students in Quebec’s public education system, but only 787 psychologists. According to Dr. Karine Gauthier, the president and co-founder of the Coalition des psychologues du réseau public québécois (CPRPQ) who is a child psychologist herself, psychologists in schools are doing more crisis intervention than actual treatment.

“There are so many crises with children, even very young kids like five-years-old who have suicidal ideation [and psychologists] are called to respond to the emergency, but this is all crisis intervention,” Gauthier said in an interview with rabble.ca. “[Psychologists] are called to assess the risk, to say ‘you need to go to the emergency room,’ […] and psychologists are so overwhelmed that there is no actual treatment because there are less psychologists but more problems and more kids. Just do the math, it is absolutely impossible to help the kids as we should help them.”

The CPRPQ’s primary goal is to make psychologists more accessible, whether in the public education system or the healthcare system. The best way to do so, says Gauthier, is by increasing the number of psychologists in Quebec and guaranteeing better working conditions and salaries. To achieve this, the CPRPQ has focused its efforts on creating a union specifically for psychologists in the public sector.

“What 95 per cent of psychologists are asking, due to the lack of representation, … is to change the law so that psychologists in the education and health systems [can] have a union,” Gauthier explained while referencing a survey conducted by the CPRPQ. “We would add a voice at the negotiating table [to] bring all the information, all the numbers about working conditions and salary.”

The current law regarding negotiations with the Quebec government—the Act respecting bargaining units in the social affairs sector—does not allow for a non-negotiator, like a working psychologist, to participate in negotiations. In Gauthier’s opinion, the lack of unique representation is a key factor in the undervaluing of psychologists, which has led to the unintended mass exodus of psychologists from the public sector.

A union for public sector psychologists

Most psychologists in the public system are currently represented by the Alliance du personnel professionnel et technique de la santé et des services sociaux (APTS), which is also responsible for advocating for 65,000 professionals that “hold over one hundred different job titles in five different sectors: diagnostic services […] rehabilitation, nutrition, psychosocial services, and prevention and clinical support,” according to the APTS website.

The APTS’ wide scope, combined with the wide range of job titles psychologists are grouped with by the Quebec government, is part of why Gauthier and her colleagues believe a separate union for psychologists is necessary. Currently, psychologists are the only APTS members and members of the government grouping who must earn a doctorate degree before entering the workforce. Their salaries mirror those of technicians and other positions that do not require the same level of schooling and as a result, psychologists in Quebec are paid significantly less than their colleagues in other provinces.

This is one reason why psychologists prefer the private sector. Additionally, those in the private sector have more autonomy. The need for care has grown so drastically, that psychologists in schools cannot set up proper treatment plans for students. Instead, schools have to concede that there is no psychologist available and that families will need to seek private care.

“The delays are so long—sometimes years and sometimes it’s never,” Gauthier added. “Some psychologists have two to five or seven schools [that they serve] and they have to drive from one school to the other and spend one day sometimes in a school per week.”

Without proper compensation and workloads that are impossible for one psychologist to manage, it is no wonder that students in elementary and high schools are not receiving the care they need. Though private care is always an option, psychologists are free to set their own rates, which can sometimes be too high for parents to pay. For Gauthier, this is an easily circumnavigated issue: Have the province pay public sector workers more and not only will you have more personnel, but more students will have access to mental health care at school, where they spend 180 days a year.

Going forward, the CPRPQ will be running a comprehensive survey of “psychologists to demonstrate with numbers that a union of psychologists remains essential to solve the attraction and retention problems that limit access to psychologists for the population in the public sector,” reads a CPRPQ statement.

Editor’s Note 2024/01/31: This article originally stated that all public sector psychologists are represented by the APTS, this has been corrected to reflect that “most” psychologists are represented by APTS.