It is time for the federal Liberals and New Democrats to engage in some unabashed Realpolitik.

Despite the seemingly late hour, they should urgently re-visit the issue of electoral reform.

Before the next election – which officially happens in October of 2025 – the two parties have to put their heads together and do whatever it takes to legislatively change the way we elect our members of parliament.

Canadian prime ministers have made some bad choices over the years. There are too many to enumerate here.

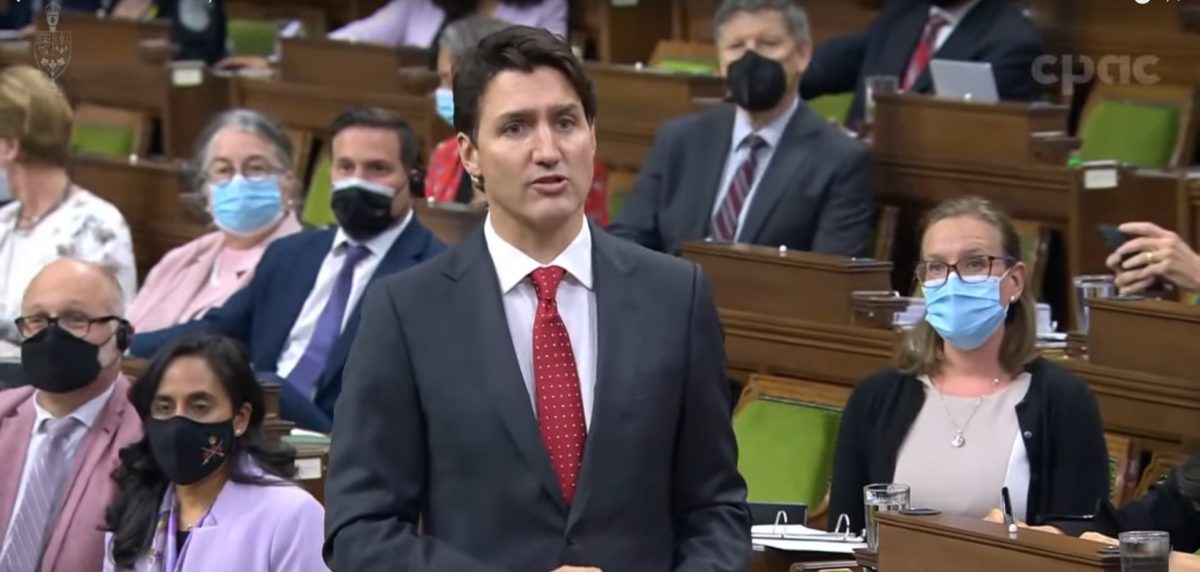

But by whatever standard we might grade bad choices, high on that list should be Justin Trudeau’s decision to welsh on his promise that the 2015 election would be the last conducted under the first-past-the-post method.

When Trudeau made that pledge, he was leader of the third party in parliament. Many of his fellow Liberals were aggrieved that despite winning only about 40 per cent of the popular vote in the 2011 election Stephen Harper’s Conservatives had managed to win a healthy majority of seats.

Back then, there was much pressure from the Liberal grassroots to change Canada’s voting system. They wanted to make sure there would never be a repeat of 2011’s unrepresentative result.

Then, in the 2015 election, the Liberals won a very similar majority to Harper’s four years earlier. Overnight their attitude toward electoral reform changed.

Once in power, Trudeau did make a feeble show of keeping his end-of-first-past-the-post promise. He set up an all-party committee tasked with proposing reform options.

But Trudeau and his fellow Liberals did their best to sabotage the reform exercise at every turn.

The Liberals were especially irked when the New Democrats on the committee made common cause with the Conservative members in favour of some sort of proportional system. The Liberals favoured a ranked ballot.

Proportional elections produce a result in which parties win seats roughly in proportion to their share of the popular vote. If your party gets 30 per cent of the votes, it gets about 30 per cent of the seats.

A ranked ballot is similar to the single member, first-past-the-post, winner-takes-all system we have now. The difference is that the ranking system allows voters to indicate second, third and fourth choices. When no candidate wins an outright majority of first choices, officials count the second and, if needed, the subsequent choices.

There are voting options that combine proportionality with first-past-the-post or ballot ranking.

In Germany, for instance, citizens get two votes, one for a single-member-constituency member (just like ours in Canada) and one for a party. And so, the German parliament, the Bundestag, has both proportional and first-past-the-post members.

The single transferable vote (STV) gives voters multiple choices in multi-seat constituencies. The winners are determined on the basis of a mathematical formula designed to assure seats are assigned proportionately.

In 2004, a citizens’ assembly recommended STV for British Columbia (BC), and in a referendum the next year more than 58 per cent of BC voters chose the new system. But the government of the day had set a high bar for change, 60 per cent in 60 per cent of the provincial ridings, and the initiative failed.

That’s the closest we have come in recent Canadian history to significant and meaningful electoral reform.

We did not get nearly that close with the Justin Trudeau Liberals’ half-hearted effort following their first election victory in 2015.

Indeed, in 2017 Trudeau pulled the plug on the effort, citing, as one excuse, the new challenges posed by the election of Donald Trump in the U.S. His other excuse was that he did not see a consensus as to what sort of new system Canadians wanted.

Liberals’ sense of entitlement has come back to bite them

The truth is that Liberal elders and seasoned operatives had been advising Trudeau to abort the reform process since the day after his victory in 2015. They told him the Liberals would never win another majority if Canada were to adopt an electoral system that included a significant element of proportionality.

Commentators have excoriated Trudeau for failing to seek the advice of experienced (and older) political professionals and for relying almost exclusively on a tight circle of friends and advisors who are all of his generation.

On electoral reform, however, Trudeau made a big mistake when he paid too close heed to the ageing Chrétien and Martin era Liberals who were whispering “Don’t do it!” in his ear.

It was advice based on Liberal activists’ unyielding belief that they are Canada’s natural governing party, that any election result other than a Liberal majority is a mere temporary aberration.

Not even their crushing defeat in 2011, when they found themselves in third place, could kill the Liberals’ sense of entitlement.

Today that arrogance has brought us to the brink of a huge Conservative majority of the sort only John Diefenbaker and Brian Mulroney won (in 1958 and 1984 respectively).

There is a long road to the next election. However, for whatever they are worth (and it’s not always a lot), all of the current polls indicate a major first-past-the-post victory in the coming election for hard-right populist demagogue Pierre Poilievre.

None of the polls show Poilievre and his Conservatives winning much more than 40 per cent of the vote. But they pretty much all put Poilievre’s party 15 to 20 points ahead of the second-place party.

As a rule, that kind of vote distribution under first-past-the-post hugely and disproportionately rewards the first-place finisher. Four votes out of ten can easily net the first-place party two thirds of the seats.

If that happens next time, we will face ideological and governance whiplash in Canada.

The Poilievre Conservatives are not your grandparents’ Progressive Conservatives. They will not see their role as providing good government with a new management team, while respecting a broad consensus on many policy fronts.

The old-style Progressive Conservatives were quite different and far less ideological.

Diefenbaker, for instance, started the process that led to universal health care in Canada, with a royal commission headed by Justice Emmett Hall. Diefenbaker was also opposed to the death penalty, and he extended the vote to First Nations’ people (then called ‘Treaty Indians’).

On taxation, trade and social programs, Brian Mulroney was more solidly on the Right than Diefenbaker.

Mulroney was greatly influenced by the neo-conservatism of Britain’s Margaret Thatcher and the U.S.’s Ronald Reagan. He cut federal social benefits and transfers to the provinces for health, social services and higher education, and pursued a free trade agreement with the U.S. which was much to the advantage of big business (and disadvantage of labour).

But Mulroney had a far more progressive approach on other policy fronts than today’s Poilievre Conservatives.

Take the environment, for instance.

Mulroney pushed the U.S. into an agreement to reduce forest-killing acid rain, made Canada the first industrialized country to sign both the Rio Convention on Biodiversity and the UN Convention on Climate Change, and spearheaded the Montreal Protocol which limiting the use of chlorofluorocarbons, a commonly used chemical that was creating a dangerous hole in the earth’s ozone layer.

Mulroney, like Diefenbaker, was also a firm opponent of South African Apartheid.

Despite his admiration for Thatcher, Mulroney very publicly opposed her at Commonwealth Heads of Government meetings when the issue of sanctions against South Africa’s white minority regime came up.

Mulroney sided with the Commonwealth’s non-white majority, in favour of sanctions; Thatcher was adamantly against.

Poilievre will try to remake Canada

We can be sure Pierre Poilievre will not seek to govern in the consensual, moderate Progressive Conservative tradition of Mulroney and Diefenbaker.

The current Conservative leader carefully avoids talking too much about his radical right agenda these days. He would rather display false empathy for ordinary people saddled with high costs for their basic needs.

But he is crystal clear about a couple of his priorities.

To start with, Poilievre has promised to abandon any sort of climate change action, starting with the federal carbon tax.

As well, he has repeatedly promised to defund the CBC, at a time when private sector corporations are abandoning the field of Canadian news and information and we need the public sector in broadcasting more than ever.

If you want to learn more about Poilievre’s other plans, you should look at the Conservative Party’s main policy document; but you will have to read the fine print carefully.

One example: the Conservatives support so-called right-to-work legislation, which would allow workers in unionized shops to opt out of paying dues. U.S. states, especially in the South, have used such measures to hobble and weaken the labour movement.

Elsewhere in their program, the Conservatives promise balanced budget legislation, the net effect of which would be to render the federal government virtually impotent, especially in a time of crisis, such as a pandemic.

Poilievre’s party adheres to the view, challenged by a number of economists, that it is not sufficient to see federal deficits decline, over time, relative to gross domestic product (GDP). He says the deficit must be reduced to zero in short order, through massive cuts to spending, regardless of the social cost.

And while proposing extreme fiscal conservatism on the spending side, the Conservatives also want to starve the government on the revenue side, by a series of reckless tax reduction measures, which would almost exclusively favour higher income Canadians. Those include big cuts to corporate and capital gains taxes.

Conservatives would also invite greater foreign control of key Canadian economic and cultural sectors, by relaxing rules that inhibit foreign ownership in the fields of broadcasting, telecommunications and air transport.

Most importantly, a Poilievre government would anchor its economic strategy around natural resource industries, in particular oil and gas, and let the environment and climate, in Shakespeare’s words, take the hindmost.

On how they would handle the signature social achievements of recent times, the Conservatives are cagey. They carefully avoid saying they will roll back the clock on every Trudeau government initiative.

But when you read what they say about childcare, for instance, emphasizing sending dollars to families rather than supporting a broader childcare framework, you have to conclude the current federal-provincial $10-per-day child care program would be in deep trouble were Poilievre to take power.

Finally, in case all of the above does not alarm you, there is this, buried deep in the Conservative program, about faith-based organizations:

“The Conservative Party supports the right of faith-based organizations to refuse the use of their facilities to individuals or groups holding views which are contrary to their beliefs or standards”.

They add that faith-based organizations should be excluded from the definition of disallowed discrimination under Human Rights legislation.

That is just a short list of how Pierre Poilievre would try to leverage his 40 per cent of the popular vote to remake the country in the Conservatives’ image.

Hence the urgency for the current governing partner parties to think outside the box and act decisively and even ruthlessly.

Ranked ballot can happen before the next election

Despite the advice grey beards gave him on electoral reform, Justin Trudeau might have gone for one option, the ranked ballot. But he could not get other parties, in particular the New Democratic Party, to agree.

New Democrats and other electoral reform advocates, including the folks at Fair Vote Canada, are allergic to the ranked ballot.

They say it would inevitably favour the party in the middle, the Liberals. Both Conservative and New Democratic voters, they argue, would likely list the notionally centrist Liberals as second choices, giving Trudeau’s party a big advantage under the ranked system.

That is an assumption which is almost impossible to test. It is based on the notion that Canadians define themselves on a two-dimensional ideological spectrum, from right to centre to left. This writer, for one, believes such a characterization of voter self-identification is wrong.

The fact is that most voters take all kinds of factors into account when making their choices at the ballot box, beyond where they fit, if anywhere, on the right-to-left ideological spectrum.

High on the list are how voters feel about the current party in power and how they perceive their own well-being.

If we were to have a ranked ballot election tomorrow, there is a good chance a lot of voters who have tended to straddle the fence between Liberals and New Democrats would rank the NDP candidate first and the Liberal second or lower.

That’s because a good portion of the electorate has grown weary of the Trudeau government after nearly nine years in power. The government’s long series of scandals, of which ArriveCan is only the most recent, is one reason for that disaffection.

The sense many voters have that the necessities of life, especially food and housing, have grown too expensive under the Liberals is another big factor.

And so, as matter of crass political calculation, the New Democrats should recognize that the ranked ballot might work in their favour, not that of the Liberals, in the coming election.

When I suggested reviving the ranked ballot option a year ago, the electoral reform crowd utterly dismissed the idea. Committed reform advocates, notably the folks at Fair Vote Canada, and New Democratic partisans, are adamant that they want proportional representation or nothing.

Such a dogmatic attachment to one sort of electoral reform is mistaken – and almost tragically so.

But it is not too late for the New Democrats to reconsider the ranked ballot as a way to finally make reform possible.

Just do it

The Liberals and New Democrats have achieved most of what was on the list for their confidence and supply agreement. The most recent big piece is the soon-to-be-announced deal on pharmacare.

Now, perhaps, it is time to turn their attention to the one big item that failed to make the list: electoral reform.

The two parties should shrug aside the fact that on February 7 the House voted down NDP MP Lisa Marie Barron’s motion to establish a National Citizen’s Assembly on electoral reform.

Such an assembly would be a worthy and democratic idea. But it is too late in the day for such slow-moving and gradualist high-mindedness.

The two partner parties need to act now, and, given the short time frame they have for instituting reform, a ranked ballot would be the best bet, and likely the only feasible option.

It is not a perfect option. There is no perfect type of reform.

But, at the very least, the ranked vote would obviate the need many voters feel to vote strategically – to vote against the party they do not want rather than for the party they do want.

As well, the ranked ballot would not be a huge and radical change for Canadians. It would leave the federal House of Commons as it is, with 338 members, each representing one constituency.

Preserving such a parliament, in which citizens have access to a single MP representing a distinct geographic area, is one of the conditions Conservatives have place on any reform initiative.

So, adopting the ranked ballot, as opposed to a more radical change, would blunt Conservative attacks (although nothing could completely stop Poilievre and his colleagues from crying foul).

The ranked vote would also be easy for Elections Canada to institute. Riding boundaries, polling stations, and other election mechanisms would all remain as they are.

The ballots would look a bit different, and would be counted differently, but such a change would not present a formidable challenge.

Finally, the ranked ballot is a system we already use in Canada, to select party leaders and to nominate candidates. It is easy to understand how a ranked-choice ballot works. We’re used to indicating first, second and third choices in a lot of aspects of our personal and professional lives.

In the end, it would indeed be an act of Realpolitik – of über-pragmatism rather than noble principle – for the Liberals and New Democrats to agree, at this late hour, to change the electoral system in such a way that 40 per cent of the popular vote would be unlikely to award an all-powerful majority of seats to a single party.

But, in a way, it would also be an act of supreme political foresight and courage.