You’re on a transatlantic flight back to Canada. You’re getting close to home and you have dutifully stowed the engrossing book you’ve been reading in your knapsack and out of easy reach, under the seat ahead of you.

Then you realize the approach to the airport will take somewhat longer than you thought, and you have deprived yourself of reading material.

You search your pockets for something to occupy your mind and all you come up with is your passport. Ok, let’s read that, you say to yourself. In all the years you’ve had this precious document you’ve never given it more than a cursory glance.

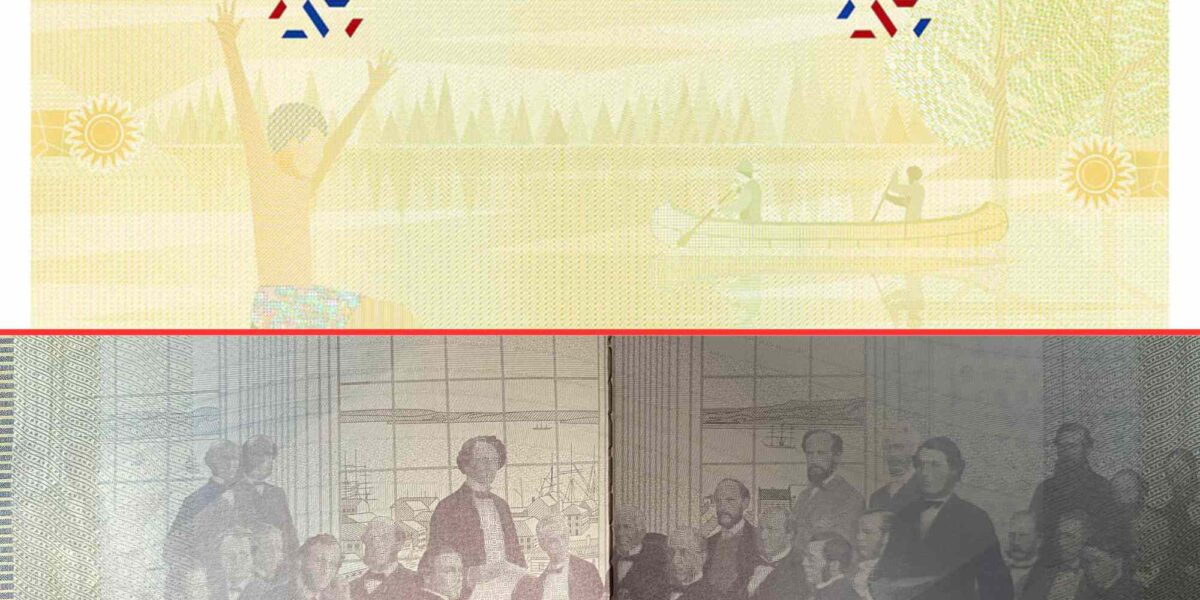

You open the official government document and start leafing through the pages. You note that each page has a different illustration in barely visible watermark form.

A cursory examination seems to indicate that the pictures are supposed to tell some kind of story, or series of linked stories, about Canada.

Canada’s story: nearly 100 per cent white

The first page depicts an Inukshuk and a feather, which the passport describes as symbols of Aboriginal peoples in Canada.

The rest of it is an all-white, if not whitewashed, story of this country.

There is an image of a statue of the explorer and colonizer (and founder of Quebec) Samuel de Champlain, followed by the well-known group portrait of the Fathers of Confederation, which is in turn followed by the equally iconic photo of Lord Strathcona driving in the last spike for the Canadian Pacific Railway.

The Fathers’ image is accompanied by a quote in English from John A. Macdonald and a different one in French from his Quebec ally Georges-Étienne Cartier.

We then get a bow to the North, with a montage of the map of Canada’s Arctic and the face of Northwest Passage explorer Joseph Bernier.

Following that, there is another montage. This one is about the Prairies, featuring railcars, oil wells and a grain elevator. No buffalo. No Cree or Métis hunters. Certainly no Louis Riel.

The passport tells about immigration with an image of a big ship docking at Halifax’s Pier 21. This is accompanied by a quote from Wilfred Laurier, in both French and English, to the effect that “freedom has no nationality”.

Next, we get a photo of the Peace Tower and the centre block of Parliament, accompanied by more political rhetoric about freedom, this time courtesy of John Diefenbaker.

That leads us to Niagara Falls, then the Memorial at the World War I battlefield at Vimy in France – plus a view of Quebec City looking up toward the Chateau Frontenac, RCMP officers on horseback, generic images of football players for the Grey Cup and hockey players (playing perhaps for Vegas or Florida) for the Stanley Cup, feminist trailblazer Nellie McClung (the only woman portrayed) holding up a plaque saying “Women are persons”, and Terry Fox running his Marathon of Hope.

The final page has a montage of Canada-at-war images, including World War I flying ace Billy Bishop, and – oddly, given Canada’s small role in that conflict – Canadian infantry in the Korean War.

The Harper version of Canada

This passport looks very much to be of its time, the Stephen Harper era.

Harper held a staunchly traditionalist and British imperialist view when it came to portraying Canada.

The former PM liked calling institutions “Royal” and took oversized pride in those times when the Empire prevailed, notably the War of 1812. That’s when we (meaning the British) supposedly routed the Americans. (The Americans have their own version, equally self-serving).

Harper forced the Canadian Museum of Civilization to rename itself the Canadian Museum of History.

Civilization was too anthropological a name for Harper. It implied too great an interest in grassroots, social and cultural practices, and in Indigenous peoples, and not enough deference for old-school political and military leaders and their role in history.

It is not surprising that a Harper-era passport would honour the NHL, a league dominated by U.S. teams, but not have a single image of any Canadian who was not white.

The passport honours the Fathers of Confederation, but neither Louis Riel nor the leaders of the Rebellions of 1837-38. Canada’s role as the northern terminus of the Underground Railroad goes unmentioned.

Nor is there a single image honouring any Canadian whose contribution was in the arts, literature, or science.

No Glenn Gould. No Maureen Forrester. No Oscar Peterson. No Hugh McLennan or Émile Nelligan or Lucy Maud Montgomery. Not even Alexander Graham Bell, or Banting and Best (who discovered insulin).

Indigenous people are, notionally, recognized, but must content themselves with a feather and some rocks.

New design – too woke or too banal?

And so, when the time came to update the passport – largely for technical, security reasons – it is not surprising the current government chose to scrap the existing, archaic imagery.

But it is too bad those who designed the new document chose to replace the Vimy Memorial and Terry Fox and all the rest with banal, generic images .

The new 2023 passport design features stylized images that appear to be teddy bears, kids playing and swimming, and some other, similar illustrations which look like they were lifted from a grade school reader.

The new passport offends by its truculent inoffensiveness. It avoids any reference to any real person, place, or event.

It is so controversy-averse, it is controversial.

Predictably the new design has attracted the ire of many of the culture warriors out there. They consider it to be yet another symptom of a too-woke-by-half Trudeau regime.

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre stomped on the new design with rhetorical hobnail boots. He was particularly offended by the omission of the Vimy image. That choice disrespects veterans, he said.

Others joined Poilievre, including the mayor of Terry Fox’s hometown and columnists such as Jen Gerson.

The truth is however, that few people ever look at the images on their passports. This writer had been a passport holder for almost five decades before he bothered to have a peek.

A country that has the time and energy to get in a lather over something as inconsequential as the design of a passport must be blessed and fortunate indeed. Such a country must have no other, bigger challenges.

Or is it that we Canadians have a near limitless ability, as one foreign observer once remarked, to “sweat the small stuff”?