First published at nmaleki.com:

Afghanistan has grown increasingly unstable since the US invasion of that country. The Taliban is bolder, better equipped, and more aggressive than at any time in the past seven years. But they were supposed to have been defeated and a new government, under President Karzai was meant to lead the country to prosperity.

This hasn’t happened.

The Taliban had time and space from which to regroup and reorganize: in Pakistan.

Information on Taliban and al Qaeda activity in Pakistan is available through the following links:

Confronting the Pakistan Problem

Inside the Pakistan-Taliban Relationship

Pakistan’s Grip on Tribal Areas is Slipping

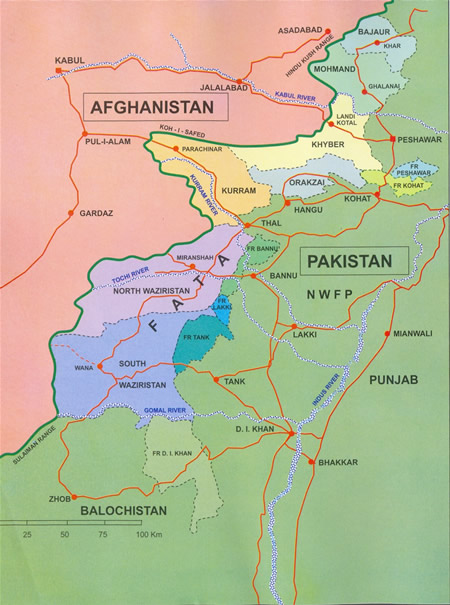

This post will briefly provide some background on the focal-point of Taliban and al Qaeda activity in Pakistan, in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). So what is the FATA, who lives there, and what is its relationship to the rest of Pakistan?

The FATA is divided into seven districts called agencies: Bajaur, Mohmand, Khyber, Orakzai, Kurram, North Waziristan, and South Waziristan. The population of about 3 million is predominantly Pashtun and tribal. Contrast this with Pakistan’s total population of about 160 million and it becomes clear that the FATA is sparsely populated.

The total Pashtun population in Pakistan and Afghanistan is about 36 million (31 million in Pakistan and 5 million in Afghanistan). Iran also has a small Pashtun population. The FATA tribes intermarry, feud, and regularly deal with their tribesmen across the border in Afghanistan, and have done so throughout their history. Cross-border ties are strong, and movement is hardly restricted by national boundaries.

The administrative system originated under the British Raj and has seen little change since. The FATA is officially under the President’s directive, who has empowered the governor of neighbouring province of the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) as his representative. The governor in turn appoints an agent for each agency of the FATA.

These agents are the most senior administrators in their region and are governed by rules established by a British Act of Parliament in 1901. These set of rules are called the Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR).

The FCR used to apply to the greater part of Pakistani territory, the NWFP until 1963, and Balochistan until 1977. The Indian Independence Act of 1947 technically made null and void the FCR yet it was maintained by Pakistan’s government in exchange for greater autonomy to the affected region, and the removal of national troops from the FATA.

Under this set of regulations, FATA tribesmen have no recourse to the constitutional, and political rights accessible to others in the country.

The tribal elders of the FTA used to hand-pick their own representatives to parliament until, in 1996, the PPP under Benazir Bhutto granted universal suffrage. Despite this, because of the application of the FCR, political parties are banned, giving religious leaders and groups a clear advantage in the process of elections since they could rely on their legal religious institutions to organize for the polls.

According to an expert on the region, Ahmed Rashid, the “political agents had sweeping punitive powers, such as imposing collective punishment on an entire tribe, levying fines, and demolishing homes of wrongdoers. (1)”

In addition to restricted political rights, the economic and social situation in the FATA is dismal. Annual per capita income is only $500, nearly half that of the rest of Pakistan. Literacy stands at 17%, with 3% for women. The national average is 56%. Clearly, the FATA is marginalized and socio-economically abandoned. Religious schools are the most available form of education, providing a further advantage to these institutions.

Health care is similarly poorly handled. The FATA’s small retinue of 524 doctors are supported by only a few hospitals.

Also, there are boundary disputes between Afghanistan and Pakistan. The border between the two, running along the FATA’s western edge, was drawn by Britain’s Sir Mortimer Durand in 1893. The Durand line divided Pashtun tribes, explaining the large numbers living on both sides.

Following India’s independence and the partition of Pakistan, Afghanistan refused to accept the Durand line, and the two neighbours have not had serious talks to resolve this issue. The border dispute adds to the uncertain state of the FATA, and promotes the very existence of a porous border in a region that is treated as a marginal appendage of the Pakistani state.

The poverty, lack of education and social services, the undefined border, and paucity of national institutions helps keep the people of the FATA in a state vulnerable to extreme insecurity: essentially open to violent or subversive control by a sufficiently organized and forceful organization such as the Taliban.

Sources:

(1) Ahmed Rashid, “Descent into Chaos,” Viking press, 2008, p. 266.

* The majority of the information provided by this post is from Ahmed Rashid’s book, “Descent into Chaos”. Read chapter 13, “Al Qaeda’s Bolt-Hole” for more detailed information.