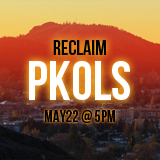

On May 22 at 5 p.m., a powerful renaming ceremony will take place in British Columbia. Name and Blood both hold important power of identity for First Nations communities, as many seek to take back both language and landscape.

Indigenous activists and their allies have been working hard on a campaign to reclaim and reinstate the traditional name of the mountain known now as Mount Douglas, and along with it, reclaim the area where the Douglas Treaties were first signed in British Columbia, Canada.

May 22, 2013, at 5 p.m., Mount Douglas will be known as PKOLS.

PKOLS Mountain — pronounced p’cawls — according to Indigenous tongue — is translated into “White Rock” or “White Head”.

According to supporters of the name change, “Stories of PKOLS go back to nearly the beginning of time for WSÁNEĆ (Saanich) people. Historically, it has been an important meeting place; and geological findings indicate that it was the last place glaciers receded from on southern Vancouver Island.”

“This is something that our elders have been calling for, for many, many years,” said WEC’KINEM (Eric Pelkey) who a hereditary chief of the Tsawout First Nation, “to bring back the names we have always used to where they belong.”

At stake here is not just a name, but a treaty relationship that centres around the Douglas Treaties (also known as the Fort Victoria Treaties), which were a number of treaties signed by First Nations communities and the colony of Vancouver Island between 1850 and 1854.

The Douglas Treaties cover approximately 930 square kilometres of land around Victoria, Saanich, Sooke, Nanaimo and Port Hardy, which were all located on Vancouver Island. These lands were exchanged through treaty for cash and goods such as clothing and blankets.

Treaty members included the Esquimalt First Nation; Becher Bay Band; Songhees First Nation; T’sou-ke Nation; Tsawout First Nation; Tsartlip First Nation; Pauquachin First Nation; Tseycum First Nations; Snuneymuxw First Nation (formerly the Nanaimo Band) and the Kwakiutl (Kwawkelth) Band.

The intention behind the treaties was to establish the presence of the Hudson Bay Company — beginning in 1850 by authority of the British Crown — in the area for the sake of settlement and economic exploitation.

Captain James Douglas oversaw the purchase of fourteen land agreements, promising no interference with the First Nations communities indigenous to the area. Along with purchasing the landscape, major areas were renamed to fit the natural contours of the British tongue.

“The reclamation of PKOLS is about more than replacing a colonial name with an Indigenous place name: it is an act of resurgence and renewal. The PKOLS campaign has really caught hold of the public’s attention and generated interest across the country. We’ve had messages from many communities who are inspired by this action and see it as the beginning of a larger movement for Indigenous people to begin to reclaim, rename and reoccupy our traditional territories,” states Jarrett Martineau of the Indigenous Nationhood movement.

Douglas had a mountain — formerly PKOLS — named in his honour; despite the fact that he nor the Hudson Bay Company kept their word to the First Nations communities in the area. In fact, the world view of the settlers was quite different than that of the Indigenous inhabitants of the land.

The general interpretation of the treaty itself states that, “With respect to the rights of the natives, you will have to confer with the chiefs of the tribes on that subject, and in your negotiations with them you are to consider the natives as the rightful possessors of such lands only as they are occupied by cultivation, or had houses built on, at the time the island came under the undivided sovereignty of Great Britain in 1846. All other land is to be regarded as waste, applicable for the purposes of colonization. The right of fishing and hunting will be continued to the natives, and when their lands are registered, and they conform to the same conditions with which other settlers are required o comply, they will enjoy the same rights and privileges,” which led to the misappropriation of land.

Without honour, and thus undeserving of the honour of having a mountain named after him, a new relationship with the land is being sought and thus old names returned to sacred areas. Oral history records that cultural ceremonies such as marriage were held at the mountain sites.

“Stories of PKOLS go back to nearly the beginning of time for W̱SÁNEĆ people to when the Creator gathered stones from near Cordova Bay (‘I’EL,ILCE in SENĆOŦEN), and stood near or upon the hill and created the surrounding mountains by casting the stones out upon the land around him (Paul, Pers. Com., 2013).”

While the Mount Douglas Park Charter states within that this land is to be environmentally protected, referring to objects and locations by their original names strengthens — culturally and through language revitalization — our connection of all to the land.

“The name PKOLS did not ‘disappear’ simply because a colonial name was overwritten on settler maps and park signs. PKOLS never lost its sacred status—it continues to be an important meeting place for many nations; and reclaiming its original name is a first step toward renewing the original promise of the treaties that were signed there”, said Martineau.

He continued, “And that means bringing things back to where they belong. As the Indigenous Nationhood Movement, we are supporting the Tsawout, WSANEC, and Songhees nations in this important work—and we will gladly support other nations rising up to do the same. I’m excited to see where things will go from here. So far, everyone has been incredibly supportive and enthusiastic.”