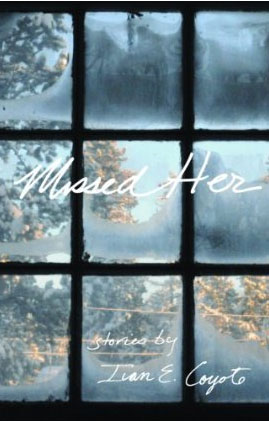

What happens when a woman with “dykey clothes” confronts a man with a bushy beard about the lesbian book he’s reading? Is life easier for a butch or a lipstick lesbian? Is it better to be queer in Whitehorse, where you’re subjected to direct questions, or in Vancouver, where PC politeness masks embarrassed confusion? Missed Her, a collection by Vancouver writer and performer Ivan E. Coyote of her Xtra! West columns, conveys these lifestyle collisions with thoughtful humour.

“Talking to Strangers” is one of the book’s most powerful vignettes. As the narrator steps into a taxi, the driver fires off questions about “your people.” Readers familiar with Coyote’s previous collections know what kinds of people her protagonist (ostensibly the same one throughout) identifies with. She wears men’s clothes but speaks in a woman’s voice. Her hair is barber-shop short but she has no beard. Her fetish for stilettos could rival Carrie Bradshaw’s, but Ivan only likes them when they’re on someone else’s feet. So she’s used to these questions. She answers them gracefully, and asks some of her own. The driver tells Ivan about his fiancée in Pakistan. They only met once, when they were four.

“He was trying to understand my lifestyle, so the least I could do was return the courtesy,” the narrator muses.

The denouement, a sudden one-line reversal, stops all stereotypes dead in their tracks. A lot of Coyote’s vignettes end with such terse reversals. Her spoken-word performances are a great complement to this narrative device. As the story winds to an end, she slows down her pace and the anticipation enhances the punch line. No wonder Coyote has a devoted following at East Vancouver venues and also criss-crosses the country to perform and teach.

Thematically, Coyote’s writing has grown in complexity and depth. Her earlier collections, especially her debut, Close to Spiderman (2000) focused on portraits of the artist as a youth navigating blurred sexual boundaries. The pain of not belonging came through, but with a dose of ribaldry. In her latest work, nostalgia seeps into the laughter. This shift is especially evident in her 2006 novel, Bow Grip, about a man who takes up the cello after his wife leaves him for a woman. The stories in Missed Her also present a more pensive first-person narrator. For example, the tone in “The Rest of Us” is mournful as Ivan returns to Whitehorse to say goodbye to her dying grandmother. In “Throwing In the Towel,” she responds with frustration to a Facebook discussion about whether butch rejection of femininity originates in misogyny. Still, undaunted optimism energises her efforts to understand and be understood.

Coyote’s positive and humorous take on labels and stereotypes contrasts with earlier, as well as contemporary, representations of lesbians. In Radcliff Hall’s 1928 Well of Loneliness, for instance, the cross-dressing heroine only gains sympathy by blaming a congenital defect. She is an “invert” belonging to a “third sex,” terms extracted from scientific manuals. In 1961, Jane Rule wrote The Desert of the Heart, in which a divorcée professor falls in love with a woman. Rejected 22 times, the novel finally found a publisher in 1964. Though Rule lived openly with her female partner on Galiano Island in B.C., the publishing world wasn’t all that eager to embrace sapphism. The image of lesbians as misfits persists today in movies such as Chloe.

For Coyote, labels are not a prognosis of terminal loneliness. They’re still important, though. In “A Butch Road Map,” she writes about her childhood in the Yukon:

“Nobody taught me how to be a butch. I didn’t even hear the word until I was twenty years old. I first became something I had no name for in solitude, and only later discovered the word for what I was, and realized there were others like me. So now I am writing myself down, sketching directions so that I can be found, or followed.”

Indeed, Coyote has become an inspiration to queers across North America. This month, she’s in California on a West Coast tour with upcoming shows in Vancouver and Victoria.—Helen Polychronakos