Last week, when my teenage daughter came back from school, she proudly showed me her newly bought t-shirt. This t-shirt had an intriguing slogan: “The invisible children.”

After asking her few questions and to my incredulous look, she told me the following: “An organisation from the U.S. came to our school and spoke to us about child soldiers in Congo and other African countries. This organisation is on a school tour in North America. It sells crafts and other items in order to help raise money that will be used to award these kids scholarships… Isn’t that great?” She was very enthusiastic.

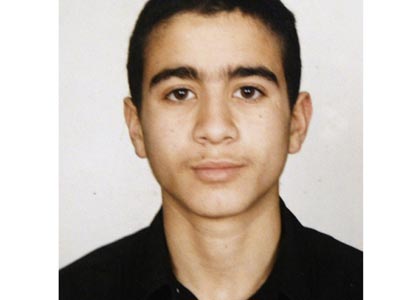

Of course this is great! But what about other child soldiers like Omar Khadr, can’t he be rehabilitated and sent to school as well? Or is the child soldier status only reserved for those war-ravaged countries where Americans have interests in keeping things safe and stable?

Unfortunately, according to the U.S. and Canadian governments, the answer to my question seems to be an outrageous “No.” Indeed, the following sad fact has now been recorded by history: Omar Khadr is the first convicted child soldier since World War II. His conviction came at an end of a shameful military trial where not a single basic principle of transparency and justice was followed and where the torture and abuse Khadr endured was simply brushed away.

This trial concluded eight long years, during which both Liberal and Conservative Canadian governments refused vehemently to repatriate him home. The acts and words that have been posed and uttered by other members of Khadr’s family seem to have taken over the ability of discernment between justice and guilt by association.

Khadr became a hot potato that no one was ready to keep and stand up for, with the exception of very few human rights groups. Unfortunately, these groups, despite their best efforts, were unsuccessful in their attempt to make this issue a mainstream one.

Even the Canadian legal system didn’t dare go to the end of the tunnel: while acknowledging his Charter rights were violated, the federal court stopped short of forcing the federal government to ask the United States to return Khadr back to Canada.

Moreover, the light hope of the closure of Guantanamo Bay has faded away after two years of the presidency of Barack Obama.

All these facts forced Khadr and his legal team to accept a guilty plea for the charges of murder, terrorism and spying. In exchange he received an additional eight-year prison term.

In the midst of the Khadr plea “bargain” another sad decision was announced by President Obama. It slipped from of the radar of many mainstream media and it had to do with child soldiers.

The U.S. president decided that “it is in the national interest of the United States to waive the application of section 404(a) [Child Service Prevention Act] to Chad, to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, to Sudan, and to Yemen.” This means that the U.S. will continue to work with and potentially provide aid to these four countries known for their use of underage soldiers.

“What the president has done is basically given everybody a pass for using child soldiers,” said Jo Becker, the children’s rights director at Human Rights Watch.

Many observers interpreted this move as a setback for the rights of child soldiers.

I don’t want to overshadow the enthusiasm shown by my daughter regarding the rights of child soldiers with my own scepticism. But, inside of me, the conviction of a child soldier, in the person of Omar Khadr, changed a lot of meanings.

Monia Mazigh is the author of “Hope and Despair: My struggle to Free My Husband Maher Arar.” She lives in Ottawa.