Change the conversation, support rabble.ca today.

Today the United States observes Martin Luther King, Jr. Day to honour the life and work of the great civil rights leader.

King is most famously remembered for his legendary “I have a dream” speech, and his leadership in the non-violent civil disobedience for civil rights for African Americans.

And rightly so. King was a transformative figure and a once-in-a-generation kind of leader. King deservingly holds the distinction of being the only individual American with a current U.S. holiday named after him.

But what’s often forgotten when most think of King — and certainly isn’t taught to my generation or portrayed in the mainstream media’s depiction of him — is that he was a champion not only of civil rights and racial equality, but also of labour rights and economic equality.

By the end of his life, King came to the belief that mere legal equality between black and white Americans was inadequate.

As Pulitzer Prize Winner Chris Hedges put it, King realized “that racial justice without economic justice was a farce.”

As labour and civil rights historian Michael J. Honey explains in his edited collection of King’s speeches on labour rights and economic justice All Labor Has Dignity, King’s vision for the civil rights movement had two phases. Phase one was for voting and civil rights. Phase two was a campaign for economic justice for all.

The speeches catalogued in Honey’s book illustrate King’s deep commitment to phase two.

Just weeks before his assassination, in a speech to striking members of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) on March 18, 1968, King reflected on the civil and political rights gained through the courageous struggles of the movement thus far.

“Now our struggle is for genuine equality,” he said, “which means economic equality.”

“For we know now that it isn’t enough to integrate lunch counters.”

“What does it profit a man to be able to eat at an integrated lunch counter if he doesn’t earn enough money to buy a hamburger and a cup of coffee?” he asked.

“What does it profit one to be able to attend an integrated school when he doesn’t earn enough money to buy his children school clothes?”

King saw unionization as a path out of poverty for America’s underprivileged. As a result, he was a vocal opponent of right to work laws which undermined unions.

King famously warned that “we must guard against being fooled by false slogans, such as ‘right to work.’ It is a law to rob us of our civil rights and job rights. Its purpose is to destroy labour unions and the freedom of collective bargaining by which unions have improved wages and working conditions of everyone.”

We in the labour movement often use this quote to remind people of the fact that King was such a strong union supporter.

But perhaps we should also remind ourselves that despite his support, King was also quite critical of unions at times. King pushed labour to be a truly transformative social movement, as it had been in the past and he though could be again in the future.

King advocated for the labour movement to forge alliances with civil rights, community and anti-poverty groups, and he warned his labour allies of the danger of not taking up broader social struggles.

In a speech to the AFL-CIO’s Fourth Constitutional Convention on December 11, 1961, King warned that the true threat to organized labour was not the few “scattered reds” within their own movement, but rather the ultra-right coalition rising in American political life.

Years later, in a speech to RWDSU District 65, one of the civil rights movement’s strongest labour allies, King warned that labour could “become as anemic as the farm bloc if its ranks thin and its importance fades.”

In hindsight, these warnings were nothing short of prophetic.

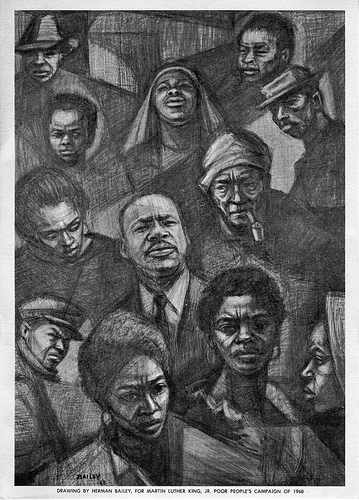

At the end of his life, King was planning a “Poor People’s Campaign” calling for mass non-violent civil disobedience and a march of America’s poor on Washington seeking a $30 billion-a-year program of social uplift including a plan for full employment, a guaranteed annual income and the construction of 500,000 affordable housing units per year. King sought an Economic Bill of Rights, not only for African Americans, but also for Native Americans, Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans and poorer whites.

Speaking of his plans on March 10, 1968 to Hospital Workers Local 1199, he said “We’re going there to engage in powerful nonviolent direct action … to bring into being an attention-getting dramatic movement, which will make it impossible for the nation to overlook these demands.”

King’s goals were bold and transformative at the time. Nowadays, a leader of his prominence calling for such changes would be unheard of.

King was killed just weeks before the Poor People’s Campaign was set to launch, in Memphis, Tennessee where he was supporting striking public sanitation workers. The Poor People’s Campaign was carried out despite King’s death, and an encampment of several thousand not unlike Occupy was set up outside the Washington Mall which was dubbed “Resurrection City.”

The encampment braved the elements with numbers in the thousands, but after several weeks with no sign of success in sight, internal divisions arose, police evictions came, and the Poor People’s Campaign officially ended.

One can only imagine how the campaign might have fared if King had been alive to see his movement come into fruition. But rather than dwelling on the past, we should draw inspiration from King’s campaign as we plan for the future.

*

While the labour movement has been on the defensive for decades and largely focused on stemming losses, a growing number have voiced the need for a transformative movement to produce the type of ‘big wins’ that can dramatically reverse current trends.

One of these voices is Stephen Lerner, architect of SEIU’s Justice for Janitors campaign, who is currently working with union and community groups on building a campaign that challenges Wall Street and corporate power.

When I reached Lerner, he spoke about the need to reproduce the type of resistance and mobilization that gave rise to the new deal and the modern labour movement.

“It was the sit down strikes, workplace occupations, physical resistance to housing evictions, and mass mobilizations demanding jobs and economic justice that built the modern labor movement.”

Lerner envisions a mass labour-community coalition uniting to “bargain with the one tenth of one percent” by identifying and taking on the billionaires and multinational corporations who control the supply chain and whose decisions impact the lives of countless individuals. According to a working paper, the campaign aims to “force the top one-tenth of the one percent to bargain directly with the people impacted by their decisions and policies.”

Asked about the role labour can play, Lerner said that “North American unions, trapped in defensive fights, can’t and won’t lead such a movement alone. Unions can help finance, support and build it, but we will only succeed if groups committed to transformational economic and politician change grow in numbers and power, and can operate independently of the legal and political restrictions unions operate under.”

In today’s America, with such poverty in the face of such unprecedented prosperity, where the top 400 Americans are richer than the bottom 150 million combined, and where the labour movement is gasping for life as multinational corporations take in record profits, a movement like King’s Poor People’s Campaign is needed now perhaps more greatly than ever.

And so today, as we remember King around the world, let’s remember him not only as a champion of civil rights and racial equality, but also of labour rights and economic equality; of human rights and dignity for all. And let’s honour him by carrying on the struggle.

Josh Mandryk is a student at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law. He’s spent the past two summers working in the labour movement and plans to practice union-side labour law.

Photo: sarahstierch / flickr