It’s been more than two decades since David Curtis settled just outside Dawson City, Yukon. As a commercial salmon fisher, carpenter, teacher and artist living off-grid outside Dawson, Curtis is an integral part of the Dawson community.

Situated on the traditional territory of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, Dawson is 279 kilometres south of the Arctic Circle. Currently, less than 10 per cent of Dawson’s food is locally sourced, but the First Nation stewards and back-to-the-land settlers are improving food security for local residents.

Six years ago, Curtis decided to give a voice to the men, women, youth and children farming, hunting and wildcrafting north of 60. His film documents the work of this vibrant agricultural community over five seasons — from mid-winter to winter the following year. Sovereign Soil looks at life and death, seasonal cycles, notions of time, and how people are living custodially in relative equilibrium with nature.

The result is a modern, multi-generational film whose life-affirming beauty, romance and emotional connection to both the land and the people will have many southern city dwellers reflecting on their own disconnect from nature, the food they eat, the people who produce it and the sovereign soil it comes from.

The barren beauty of the winter landscape belies the vibrant life it harbours beneath. Brussels sprouts on frozen stalks have been busy turning starch into sugars to sweeten their bitter buds for organic farmer Otto Muehlbach, originally from Germany.

Muehlbach refused to buy into the unsustainable settler vision that “bigger is better,” opting instead for small-scale organic, requiring minimal machinery and having negligible impact on the life systems surrounding his farm.

Fruit trees planted in 1988 by American John Melton take shelter in a makeshift, snow-insulated greenhouse while he and his South African-born partner, Kim Melton, use this time to graft new trees.

After 30 years of caring for his trees in pots, Melton made the bold step of planting some trees directly into the ground. Two seasons later, they are doing well. Melton has partnered with the University of Saskatchewan to research frost resistance in apples.

With the exception of dry goods like flour, sugar, salt, coffee, ketchup and of course toilet paper, New Yorker Jan Couture and her husband, B.C. native Gerry, were self-sustaining while raising their large family. Jan and her daughter even shot and dressed a moose in their younger days.

Grant Dowdell arrived in the Yukon from Toronto in 1970, and together with his English-born partner, Karen Digby, live and farm off grid.

Sylvia Frisch and Berwyn Larson are home schooling their two daughters while producing birch syrup and an assortment of food products that are affordable for the average northerner.

These are the tried and true organic famers who lovingly stake out their space and grow an incredible variety of vegetables, fruits, herbs and flowers where few others would dare to plant, let alone choose to thrive.

These are the settlers’ stories, but there’s an abundance of First Nation wisdom, knowledge and expertise being re-introduced and shared within this tight northern community.

To improve food security, the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in community started a teaching and working farm in 2015. This farm for land-based health, wellness and local food production is based on the philosophy of Nänkäk nishi tr’ënòshe gha hëtr’ohǫh’ąy: “Land where we learn to grow our food,” which centers around living on the land and with the land by relying on First Nations’ stories and teachings.

Jackie Olson, a Tr’ondek citizen and proud Dawsonite, grew up living on the land. Olson shares the knowledge of her ancestors and their culture, which reveres the reciprocal relationship humans have with all life. She explains to younger generations that when a raven circles over one spot it tells hunters there’s a moose below. In return, you must give thanks to the raven by gifting some of that moose meat.

Nänkäk nishi tr’ënòshe gha hëtr’ohǫh’ąy is a self-governing farm where diversification is key to the health of the land, plants, animals and people. It’s the human relationships that matter just as much as the food.

The teaching and working farm has had a tremendously positive impact on First Nations youth, giving them a purpose as well as hope for the future. According to Curtis, “We need to support young people getting into agriculture. Agriculture is the second largest polluter next to oil and gas. Small scale farming addresses that. The teaching farm encourages their youth to take an active role on the farm.”

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in never ceded their land. Twenty years ago, a land claims agreement sighed by the federal, provincial and First Nations governments ensured self-governance to the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in.

Curtis says, “The community is working towards a progressive partnership with the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in to ensure that the Truth and Reconciliation calls to action are followed through. That means ongoing discussion and ongoing process within the community.”

Sovereign Soil, Curtis’ first feature documentary, is part of a planned triptych of works within his community exploring the intimacies of human relationships to land.

The National Film Board of Canada (NFB) premiered Curtis’ remarkable Sovereign Soil at the Guelph Film Festival last fall and is now screening it across the country.

Doreen Nicoll is a freelance writer, teacher, social activist and member of several community organizations working diligently to end poverty, hunger and gendered violence.

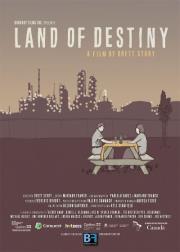

Image: Sovereign Soil