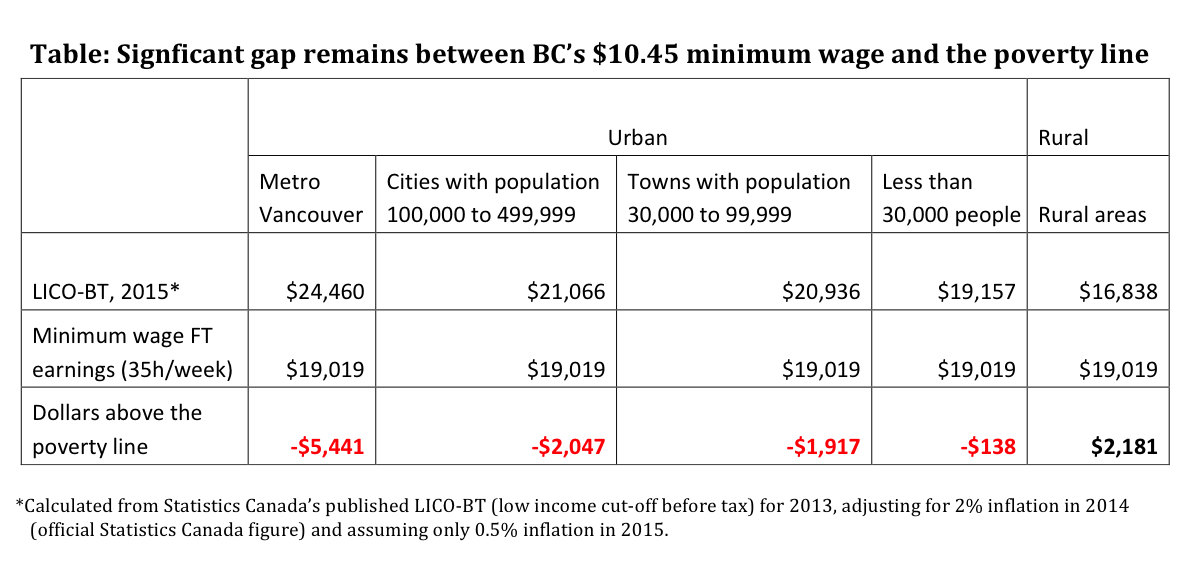

After close to three years of no change, the B.C. minimum wage was overdue for an increase. But the measly raise announced this week falls far short of what is necessary. The 20 cents per hour increase, scheduled to come into effect on Sept 15, 2015, amounts to a raise of just under 2 per cent over more than 3 years. A $10.45 minimum wage will leave the workers who earn it thousands of dollars below the poverty line even if they work full year, full time. A worker getting paid $10.45 per hour, 35 hours per week for the full year would earn $19,019. Note that with the minimum wage increase only kicking in mid-September, this is slightly more than a minimum wage employee would actually earn, but I wanted to keep the calculation simpler.

An annual income of $19,019 is below the poverty line for a single individual with no dependents in all but rural areas. For reference, only 12 per cent of B.C.’s population lived in rural areas in 2014.

In Metro Vancouver, a worker struggling to get by on minimum wage will be almost $5,500 below the poverty line for a single person this year. For a single parent with one child, the gap between minimum wage income and the poverty line would be over $11,000. About 53 per cent of B.C.’s population lives in Metro Vancouver, according to BC Stats.

In one of B.C.’s bigger cities — cities like Victoria, Abbotsford, Kelowna, Kamloops, Nanaimo, Prince George — a full-time, full-year minimum-wage worker would be about $2,000 below the poverty line for a single person. Even in small towns with population under 30,000 — including Cranbrook, Powell River, Port Alberni, Williams Lake — a full-time, full-year minimum-wage worked won’t clear the poverty line.

This is shameful.

Even with this measly 20-cents increase, B.C.’s lowest-paid workers have lost ground since 2012, when the gap between the poverty line and full-time minimum-wage income was just shy of $5,000 for a single person living in Metro Vancouver.

In a 2011 piece published by the CCPA, the last time B.C. was having the minimum-wage debate, we argued that the B.C. government should develop a clear rationale for setting the minimum wage and stick to it. We still aren’t there. We have not moved past setting the minimum wage arbitrarily.

It’s time to step back and ask: what is the minimum wage for? Then it can be set appropriately to meet these goals. Poverty reduction is one rationale that makes a lot of sense:

We propose that a single person working full-time year-round should earn (at least) enough to live above the poverty line. The idea that someone working full-time, full-year should be able to get out of poverty is a clear, transparent policy decision that should determine the minimum wage in B.C. and in other provinces.

This should be a pretty easy rationale to get behind — few people will argue in favour of maintaining a group of working poor.

Equally important is to legislate regularly scheduled increases tied to inflation, to ensure low-wage workers do not face what amounts to a pay cut as a result of rising prices.

We now have inflation indexing, and this is a step forward. But we still don’t have a minimum wage that puts all full-time workers above the poverty line. Without it, indexing achieves very little. At the end of the day, a poverty wage indexed for inflation remains a poverty wage.