In September, when the B.C. government tabled its First Quarterly Report on the B.C. budget the big story was on plummeting natural gas royalties, which means cuts to public services in order to keep the budget balance in check. As the update states on page 6:

The deterioration in natural gas royalty revenue is the main issue that needs to be managed in order to balance the budget. … Government will need to adopt revenue and/or expense measures as part of its management strategy. … Immediate measures include a freeze on hiring across the BC Public Service and a salary freeze for all public sector excluded management staff, including those in Crown corporations and the SUCH sector (schools, universities, colleges and health organizations).

This highlights the folly of relying on natural resource royalties to fund core services like health care and education. For the 2012/13 year, expected natural gas royalties are a mere $157 million, 0.3 per cent of budget revenues, and way down from the heady days of 2005/06 when gas royalties brought in a record $1.9 billion to the Treasury. This shortfall comes even as B.C. experiences way higher production levels — in 2011, a record high total of 41.4 billion cubic metres, one-third higher than 31.9 billion in 2005 (current data here and historical data here). Production in 2012 looks to land in the same territory as 2011 based on year-to-date estimates.

Recent developments also expose a major flaw in how B.C. administers non-renewable resources, at least in terms of public benefits from extraction of a publicly owned resource. While B.C.’s Ministry of Energy and Mines has data going back to 1966 on production levels of natural gas, levels were fairly low through to the 1990s, when production really started to take off. Claims of a hostile business climate under the NDP do not square with the fact that total production roughly doubled between 1991 and 2001.

The advent of fracking in the mid-2000s set off a new boom, and the B.C. government hopes to double or even triple current production by exporting Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) to Asia. I have expressed major reservations about B.C.’s Natural Gas Strategy for being immoral, illegal and bad economics, but let’s put aside climate concerns for the moment. One important justification for expansion of the gas industry is the resource royalties back to the Treasury, so it is worth taking a look at whether B.C.’s royalty regime is up to the task.

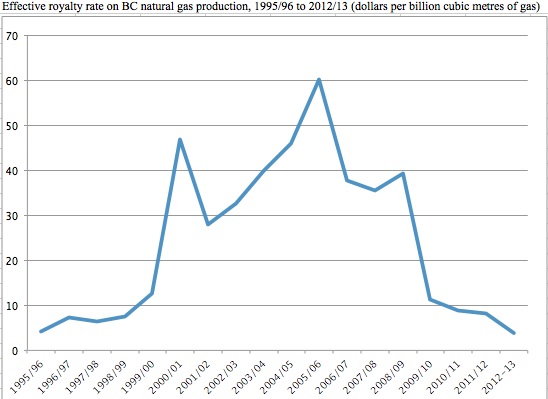

The formulae for calculating royalties are complex, but a straightforward way to look at budgetary impact is to estimate the effective royalty, by taking total royalties and dividing by production levels. Available revenue data was not easy to get before 1995, but the graph above shows what things look like (note that royalties are on the budget fiscal year and production on a calendar year basis).

Back at the 2005/06 peak for revenues, the effective royalty was just over $60 per thousand cubic metres of natural gas. In fact, between 2000/01 and 2008/09 the average effective royalty was over $40 per thousand cubic metres. It then drops dramatically from 2009/10 to the projected 2012/13 royalty of less than $4 per thousand cubic metres, a collapse of 93 per cent. Royalties are calculated based on a mix of volume and price data, and fracking has driven up production across North America since 2005, with prices falling from a high of about $7 per gigajoule (GJ) in 2005 to under $2 earlier this year.

There are other ways of showing this collapse. As a share of provincial GDP, royalties were 1.13 per cent in 2005/06, but have fallen to just 0.07 per cent of GDP in 2012/13. On a per capita basis, royalties fell from $458 per British Columbian to just $34 over the same time period.

Natural gas is not going anywhere, it is a finite resource. Our royalty regime should be based on the amount extracted not market price. Today, many gas companies are not making money, but they are keeping production levels high, probably to keep cash flow going. Higher royalties based on quantity would better value the resource we are extracting, and if market prices fall too low would make it uneconomical to extract gas.

The key point is that we need a more effective royalty regime, as under current policies B.C. is giving away its gas resources. Doubling or tripling production, even if it were not bad news for the climate, may not deliver on promises of huge new royalties under the current price structure, particularly since the price spread between Asia and North America is not likely to hold for 30-40 years as is commonly assumed in government projections (many others are building LNG capacity).

That said, I’m not a fan of using non-renewable resource royalties to fund current budget expenditures. This is like spending your inheritance on throwing a big party. Instead, we should aim for something more like the Norwegian model, which banks royalties for the long term and for investment in clean energy sources. What we really need is a strategic management framework that winds down our gas reserves over the next couple of decades, facilitates the transition to a zero carbon economy, and on the way provides revenues needed to make new public investments that green our infrastructure.