There was a time when the idea of biofuel — energy produced by simply growing plants, instead of digging it up from the ground — seemed like it would solve many environmental and even social problems. Of course, this was something that maybe we wanted to all believe — simply by changing the pump at the gas station, eventually we would be able use our planes, trains and automobiles guilt-free. Then the doubts started to emerge, and like a poorly built dam, the water eventually burst.

Today, as far as most environmentalists are concerned, the panacea of biofuels-as-saviour is dead. We have seen that most biofuel production is actually more fuel-intensive than using the equivalent amount of pure gasoline. The land that has been cut down in tropical forests, from the Amazon to Indonesia is enough to condemn the process, especially because the monocrop plantations mean the end of all biodiversity. In Brazil, they have been called ‘green deserts’ because they also suck up vast amounts of water. Additionally, many farmers and Indigenous Peoples have been kicked off these lands, and a large part of the recent food crises worldwide has been blamed on the amount of crops being taken off the market to feed our cars. There are many ways biofuels can be produced sustainably, but these cases are the exception.

In the fight against climate change, many companies have made their money producing biofuels, often at great cost to the environment and local communities. It seems that one of the first biofuels companies has entered Peru in recent years, and is continuing this costly legacy. The company is called Grupo Romero, a Chilean consortium, and they have been granted thousands of hectares within the Peruvian Amazon to carry out their business, with plans to expand.

On the other side are a number of Indigenous Kichwa (not to be confused with the highland Quechuas) and mestizo communities in the province of San Martin where the plantations are located. After my time with communities surrounding Bagua, I made the 12 hour journey to Lamas, where the headquarters of the Centro Sachamama and the Ethnic Council of the Amazonian Kichwa People (CEPKA) both reside. There, I met up with Marcos, who heads the Centro, apart from being a full time teacher in a nearby community. I also met up with a number of Apus (traditional leaders) and youth activists at the same time.

Marcos

The picture they painted was not pretty, and the problem was far from recent. It had literally started with conquest and colonization, but in more recent times, many communities’ problems stemmed from not being recognized by the Peruvian government as Indigenous communities. Why? According to Marcos, “They hired a government worker from the Ministry of Agriculture, who didn’t even travel to the communities. He then wrote a report, saying they didn’t wear their traditional clothes, practice their traditions, and many didn’t speak the language. They then concluded that these weren’t Native communities (communidades nativas).” I began to wonder if the government had studied Canadian history.

As a result of their non-recognition, they lost out on rights to their communal lands, territories, and resources, including the “Step Mountains” (Cordillera Escalera), which had been converted into a “Protected Area” outside of their control. However, according to The Waman Wasi Centre’s director, Luis Romero, “The government didn’t apply the laws of the constitution, and therefore the park itself is illegal in its creation.” Moreover, it created a precedent whereby Indigenous and local communities didn’t have to be consulted for government projects. Enter Grupo Romero.

In 2005, according to Misael Salas Amasifuen, President of the Kichwa Council, Grupo Romero was granted 3,000 hectares (about 7,500 acres) of ancient-growth Amazon forest just kilometres north of the Kichwa communities in San Martin State. Since then, they have either been granted another 3,000 hectares, with another 4,000 to be approved, or the 7,000 hectares to be soon approved — sources weren’t sure. The land was rapidly being deforested to create palm plantations, the fruits of which would be turned into oil. Many of the local communities — Kichwa and Mestiza (mixed race/heritage) — were very concerned that the plantation would expand into their lands, and the impacts on the environment — from chemical and water contamination — would be irreversible.

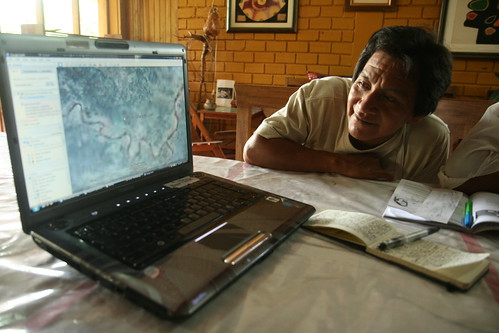

Surprisingly, we were able to find the site in question on Google Earth (see it here), where the deforestation was evident. Many of the Apus had never seen such a representation of their world, and were very excited to explore their world from above. Not content with simply seeing the site on the internet, I inquired about making a trip to visit the site and the communities in question. It would not be so easy, and might require at least 6 hours of hiking, I was told, but President Misael just happened to be available, and had not had the opportunity to visit the site himself, being a few hours away through treacherous mountain passes.

Kichwa “Apu”

We started the trip that very Sunday afternoon, making it as far as Pongo, and narrowly missing the last truck to Barranquita, the capital of the district of the same name, where the Kichwa communities were. After an hour on the side of the road last night, we finally rented a room for the night, sure no more trucks would pass by. Instead we woke up for the 4am truck, and rode in the back of the pickup the two hours to Barranquita. There, we located a man named Jander, President of the local Barranquita District Defence Committee. He made a call on the community loudspeaker to have the rest of the Committee assemble, and we started to talk.

Initially, the Committee was suspicious of my role, as there had apparently been many NGOs and media folk who had passed through before, using the communities’ issue for their own gain, and not following up. Confident with my past experience working with other Indigenous communities, we proceeded. The Committee was made up of representatives of not just the town — including the mayor– but also the many Native communities around. “The expansion of the plantation is a threat to all our communities, but we couldn’t go about opposing it officially, because of the repercussions. So we set up this committee, which allows for the community leaders to participate, and for us to organize events together,” Jander made clear, referring to a number of marches and mobilizations led already.

The Mayor, Jander, and President Misael

To get a sense of the Kichwa communities’ own understanding, we hired a boat driver to take us down the river that day. After a few hours of upstream travel one of the Amazon’s tributaries, including many instances where we had to push the boat over obstacles, we finally made it to the Kichwa community of El Piñal. There, the Apu, Merino Amasifuen Ishuiza, and many community members greeted us and offered chicha, a drink made from fermented corn, as we gathered in the shade. The mood lightened a bit after Misael made a little joke about me falling in the water and soaking all my clothes, which wouldn’t dry until the next day.

We quickly began a discussion of the community’s concerns. Merino supported Marco’s earlier assertion: “The Agriculture Ministry worker never even came to our community, so we’re going to reject their report when they try to present it.” The whole issue was fairly patronizing, the government setting the standards of how “Native” a community had to be, then deciding this community wasn’t, without ever visiting. After a little while, the community’s bilingual teacher arrived, and the conversation with CEPKA’s president switched fully into Kichwa, proving beyond any doubt that this was a community with an Indigenous past and present.

Merino, far right, leading us on a tour of the community of El Pinal

Why was the government so intent not to recognize their Native heritage? “They don’t want to recognize us because they will have to recognize our land rights. If they recognize our rights, they can’t easily give away the land to companies like Grupo Romero,” answered Merino. Grupo Romero’s presence then was a direct threat — not only to their ancestral territories, but even to their recognition as Indigenous People, because the government saw it as an impediment in its dealings with companies. Before we got to go further into detail, our boat driver decided it was time to go. The Apu took me on a quick tour around the community, introducing me to a number of families who were very eager to have their photos taken. For a few minutes, I was treated like a celebrity in the community, until the boat driver came back upset that we still weren’t in the boat.

Children in El Piñal

I promised to come back again someday, with more time and photos in hand, and we set out downstream this time. A short hour later, the sun was down, and we were only able to guide our boat by the stars and a small flashlight I had brought. After an hour of running into obstacles and getting stuck in shallow areas, we pulled up near a hut belonging to our boat captain. We ended up spending the night there, sleeping under mosquito nets that weren’t as adept at keeping out the bugs that crawled between the wooden planks we slept on. In the morning, we set out again, finishing the last hour into Barranquita for 7 a.m., and catching a truck back to Pongo.

A nice place to crash for the night

Back at the crossroads of Pongo, we found a van that would take us up to El Progreso, more or less where the plantations were said to be. At this point, we were travelling based on what I thought I remembered from Google Maps, as we got off the van and started to walk around town. After a while not finding anything, we finally got a little motorcycle-taxi to take us to the site, which in fact happened to be the next town over.

Innocent looking palm fruit

Now, I won’t say that we did anything illegal by paying an unofficial visit to the plantation, so let’s just say that somehow managed to get some photos from inside the grounds. We somehow got them, without a plantation worker asleep amidst the palm plants waking up, and with only about 40 cuts from barbed-wire fences and even sharper tropical brush. In the end, after an hour, a bit of luck not getting too lost, and a liberal amount of iodine and bandaids, we had the evidence we wanted for the communities.

Old growth forest, cut down and burnt to make room for Palm plantation

We caught one truck after another to arrive in Lamas that afternoon, from where I leaving for Lima later that night. Mr. Salas took me to visit the Waman Wasi centre, where I had the chance to exchange photos with the centre’s Luis Romero and discuss the Kichwa situation. Waman Wasi’s understanding was that the Grupo Romero situation was likely just one of many factors in the government’s rejection of Native status for the communities, the biggest of which was potential oil reserves underneath the land we were literally standing on. Really, it seemed the communities were stuck in a black hole, where the regional government and central government were conspiring to keep them without rights to self-determination while opening up the lands to outside companies.

Green Desert of destruction carved into the Amazon

That very day, April 13, 2010, the communities issued their own declaration (available in Spanish here, or on YouTube featuring Misael and Merino). As promised, they rejected the government’s conclusions, call for the simple application of their rights as per the constitution, the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples’ and ILO Convention 169, and consider the government to be provoking their communities. Clearly, the issue is far from being resolved, but only ramping up, and it is now more than ever that the Kichwa would benefit from any support. The governments, companies, and international institutions involved have been informed that their continued violations of Kichwa rights and self-determination cannot go on. How will they respond?

I continued my voyage towards Cochabamba the next day to participate in the World Peoples’ Climate Conference, and hopefully see this type of issue dealt with.