In April 2015, the Canadian network for Women’s Shelters and Transition Homes released their report, “Shelter Voices.” It documented one day in the life of Canada’s women’s shelters and transition houses. This report is a wake-up call for all Canadians.

Founded by grassroots women’s organizations, women’s shelters, also known as transition houses, began proliferating across Canada in the early 1970s. Transition House in Vancouver and Ishtar in Langley, B.C.; Oasis House in Alberta; Interval House in Saskatoon; and Interval House in Toronto were the first to open their doors to women and children in 1973.

Run mainly by volunteers from the women’s movement, these safe havens often received assistance from charitable organizations and religious groups.

Today, there are close to 600 emergency shelters and transition houses serving women and children across Canada. Funding comes from various levels of government, corporate gifts, sponsorships, donations and fundraising.

Services offered have expanded over the years to include crisis line counselling; counselling for residents as well as women living in the community; court support workers; connecting women to services; providing public education, advocacy and awareness; and some work with men. Many also have specialized services for Aboriginal women, women with disabilities, women dealing with substance abuse and/or mental health, and for trafficked women.

On Nov. 25, 2013, the Canadian Network of Women’s Shelters and Transition Houses asked its 350 members to complete an identical questionnaire detailing a typical day in the life of women’s shelters. A total of 231 shelters participated.

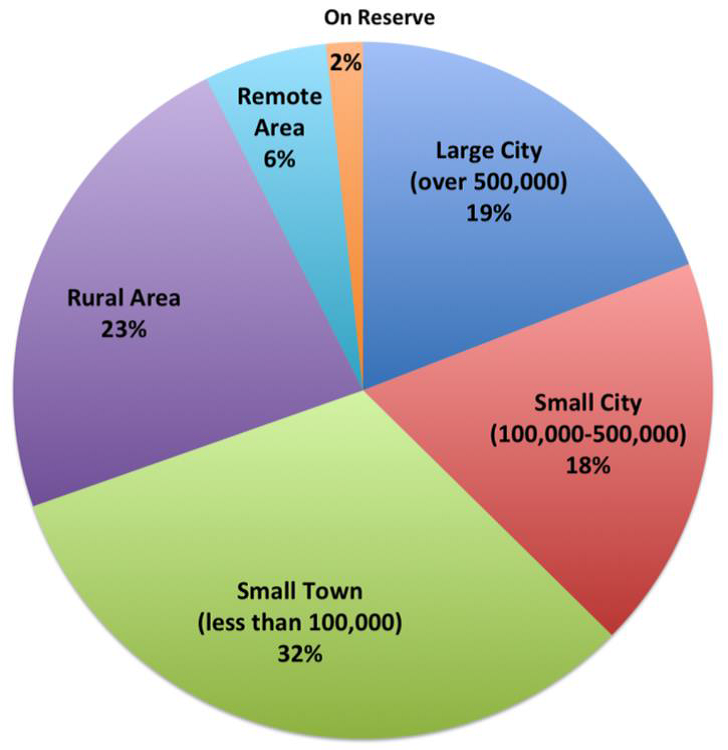

Participating shelters included 81 per cent emergency shelters; 10 per cent second stage housing where women transition from emergency shelters to long term housing; 9 per cent mixed accommodation. The distribution of shelters was interesting with 19 per cent located in large urban areas while smaller cities, towns and rural areas made up 73 per cent. Remote areas accounted for 6 per cent and reserves only 2 per cent.

Here’s a sample of the findings:

- 3,781 women and 2,508 children were sheltered

- 114 of those women were pregnant

- 110 of the women had been threatened with a gun

- 302 women and 221 children could not be accommodated

There is a shortage of second stage housing, also known as transitional housing. There is also a critical shortage of affordable housing, as well as social housing, in many parts of this country. This means women may find themselves living at emergency shelters for long periods of time. In some parts of the country it can be a year. This slow turn around limits capacity and means that shelters are unable to accept new women and children as quickly as is necessary.

If you’re turned away from the shelter because it’s full, imagine how much more difficult it will be to try to leave a second time.

In Hamilton 1,200 women a year are unable to find emergency shelter. This problem will only worsen when Honouring the Circle transitional shelter closes its doors in June. Home to 15 women and their children, the shelter has had its annual federal funding of $200,000 cut.

Phoenix Place, another transitional shelter in Hamilton, is home to 10 women and their children. The annual budget is $220,000. The provincial government contributes 30 per cent of the budget and the City of Hamilton 5 per cent. The remaining 65 per cent comes from donations and fund raising. The shelter has a $3,000 monthly deficit. An anonymous donor recently gave Phoenix Place $35,000 to keep the shelter from closing its doors in August, but the shelter will return to its precarious financial situation unless it finds adequate reliable funding.

Halton Region covers a large area, but is known for having two cities considered the top mid-sized cities in Canada, Burlington and Oakville. Yet, even this affluent region turned 390 families away from its two shelters in 2014. These shelters were at capacity because women are having an increasingly difficult time finding transitional and affordable permanent housing. Emergency shelter stays are averaging upwards of a year.

Canadians deserve better funding of emergency and second stage shelter services. They also deserve a national housing policy to address affordable and safe housing for all Canadians. The icing on the cake would be a national action plan on violence against women.

These are all great issues to raise when candidates come to your door canvassing your support during the federal election.

If you are a woman experiencing abuse, help is just a click away.