Cards on the table, first: I’m completely on-side with the sex trade workers in the current battle against the against the Harper government’s “made-in-Canada” Nordic model legislation. That legislation is dangerous. It will force the trade underground and leave these women (because all but a handful, distinguished by the term “male prostitutes,” are women) vulnerable to every kind of abuse.

We have here, first and foremost, an occupational health and safety matter. That is, or should be, everyone’s primary concern at the moment.

I have no time for priggish moralizers when lives are literally at stake, be they social conservatives or angry radicals. And that goes for the bizarre “john school” nonsense, too, where, in return for staying out of the criminal justice system, you get to be preached to for hours by the Salvation Army. Were I in that spot, I might well prefer prison.

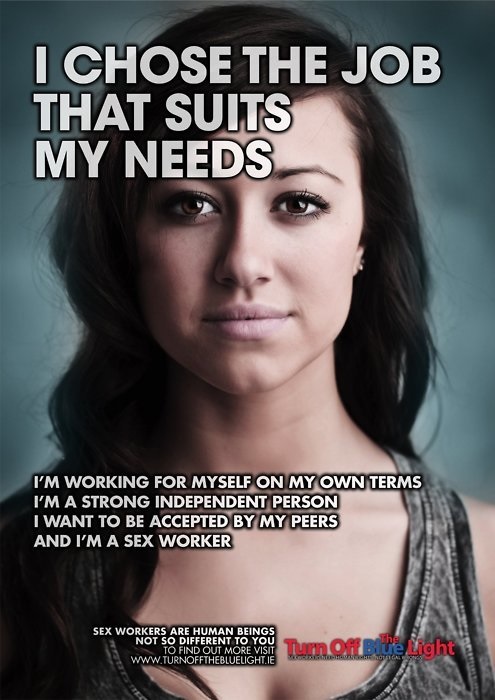

Nor do I believe that all prostitutes are hapless victims upon whom unspeakable violence and degradation are perpetrated. Let us, for the sake of preserving their dignity, spare these women the Lady Bountiful treatment. They have agency. They are our equals. They are workers. Let’s think of them that way.

Framing the question thus helps us to avoid invoking pointlessly general issues of principle. Bare principle alone has never guided anyone through the complex issues of everyday life, and it is precisely with those issues that we must come to grips. Obtaining money or other considerations for bodily labour is, after all, not confined to prostitution per se. “Prostitution is only a particular expression of the universal prostitution of the worker,” said Karl Marx, and he had a point. Why is selling other forms of labour power “moral,” as a general proposition? We are all in the belly of the beast: workers, through the alienated labour that they perform, perpetuate the very system that enslaves them. And yet — they must work.

Adding the gender dimension to this simply highlights the difficulty. Under patriarchy, the objectification of women is a commonplace. But within the all-pervasive gender power relations that mark and define our society, women still have to live. They make the (limited) choices that they must, within that oppressive context. Prostitution as commodification of women? Certainly. But all labour, whatever it might be, is a commodity. We (the “99%,” if you like) literally sell ourselves for money by entering the job market. And we are all, more or less, deformed, oppressed and exploited by it.

In the case of women, pay equity is still a dream for far too many. Sexual harassment in the workplace is hardly rare. Women are still ghettoized, and the work that many of them do remains undervalued. It’s no surprise that an active minority choose the more lucrative sex trade. Porn actresses make much more money than the men they engage on camera. Strippers pull in more in one night than secretaries do in a week. High-priced call-girls can do far better than that. It’s the market, meaning that there’s a demand, and, under the twin yokes of patriarchy and capitalism, many women freely choose to satisfy it — within, of course, the limited frame permitted by the system to any of us.

Mrs. Grundy is, unfortunately, alive and well in the current debate. She infiltrates too many of the discussions, progressive or otherwise. This comes across more clearly on the Right, who can barely prevent their lips from curling as they describe those stereotypical poor, degraded and unwilling sex trade workers. But it’s there on the left as well, if more subtly. Those who decry the material use of women as fashion models (bearing on their backs the seasonal “collections” of male fantasists) or as advertising come-ons, or as “sex objects” in general, defend the sex trade in the most liberated terms. Eager to overthrow oppressive conventional proprieties, some progressives put sexual objectification in parentheses for sex trade workers—or toss the notion out entirely. But there’s an obvious disjunct here, when such a glaring exception is created—even if it’s one that, at least in my view, should become the rule.

PETA, for example, gets no such break. It runs campaigns that I’m admittedly not comfortable with, and it has been the target of considerable venom from those of the feminist persuasion. But the only difference here is that the half-naked women labelling themselves as cuts of meat are freely choosing to do this for a cause instead of for cash. “Dehumanizing?” To an animal rights activist who believes that sentient animals are on the same plane as humans, that term would have little meaning. But setting that aside, why is this tactic more dehumanizing than most paid work? Including sex work?

OK, some will respond — as they do with the “Femen,” a mutant feminist organization run by a man — why is it only women who strip for political effect? An excellent question, one that calls for considerable analysis: but, as noted, the vast majority of prostitutes are women, too. Is there an element of condescension, perhaps, in their exemption?

Progressives, of course, instinctively reject the notion of human commodification. We strain, often clumsily, to achieve that possible other world, in which we are no longer bought and sold on the marketplace, but free — even if the latter concept is sorely vexed. But we also live in this one. Women and men use the master’s tools as the only ones ready to hand. Most times, whether we are sex workers or other some other kind of worker, our bodies are indeed tools of the trade. Allowing them to be used that way is not a force for change. But almost all of us do it in order to survive. We locate ourselves at the dictate of others. Our bodies are disciplined, skilled, re-shaped. Our brains and our muscles — and in the case of sex trade workers, sexual organs — are employed.

Yet even in that future cooperative, egalitarian, moneyless society that some of us dream of, there will still be exchanges of considerations, the oil that keeps any society running. We will help each other, in other words: but our labour would no longer be alienated, that is, owned by others. You repair garden implements, she’ll get the food, I’ll cook a meal. It’s hard to imagine that consensual sexual favours would be entirely left out of this free flow of social exchange. But, shorn of the ages-old baggage of moralism and patriarchy, why would anyone think twice about it?

Solidarity with the sex trade is just a specific instance of solidarity with workers in general. We are now addressing ourselves, as we must, to the danger that many of those workers face. In fact, we should rightly oppose measures that create, maintain or worsen danger for any workers, whether it’s a sketchy john or improperly secured overhead electrical wires. But true solidarity requires an inward appreciation of our own status as objects and bodily commodities in the barbarous economy of the here and now.