It’s 2017 and Canadians are celebrating Canada’s 150th birthday. The official government of Canada website encourages Canadians to “celebrate all that makes us who we are as a country.” As a white settler enjoying life on stolen lands and broken promises, I’m unable to join in this celebration.

I don’t remember learning much about First Nations, Inuit or Metis peoples at school. I know for a fact, I learned absolutely nothing about treaties, the Indian Act or residential schools. In fact, it was as an adult that I realized at least four children I went to school with and called friends were First Nations children who had been taken from their families of origin as part of the Sixties Scoop.

Indigenous nations were of benefit to explorers and settlers until their usefulness was dwarfed by valuable resources the land and waterways held. Once the scales tipped in favour of commodities, Indigenous lives became expendable.

If the objective is genocide then the most efficient way to achieve this goal is to target the women and children. The Indian Act tried to eradicate First Nations women while residential schools, the Sixties Scoop, and the child welfare system set their sights on Indigenous children and youth.

Since first contact, Europeans have undermined and usurped the authority and power of First Nations, Inuit and Metis women and girls. The implementation of the Indian Act effectively stripped First Nations women and girls of their basic human rights.

Systemic oppresssion

Rates of violence against women vary widely across Canada, but Indigenous women are 2.5 times more likely to be victims of violence than non-Indigenous women.

Saskatchewan comprehensively reviewed its long-term missing persons’ files and found that while Aboriginal women make up six per cent of the population, they account for 60 per cent of its missing women.

Every six days, a woman in Canada is killed by a current or former intimate partner. Indigenous women experience femicide rates six to seven times greater than non-Indigenous women. Indigenous women are almost three times more likely to be killed by a stranger than non-Indigenous women.

The RCMP estimate a total of 1,181 Indigenous women went missing or were murdered between 1980 and 2012. Grassroots organizations and the Minister of the Status of Women believe the number is closer to 4,000. But, neither number even begins to reflect the true sum of Indigenous women and girls who have been the victims of large scale femicide over the past 150 years.

Traditionally, Indigenous women were the givers of life and as such, lineage was traced through mothers and family units were often matrilocal in nature. Women were a child’s first teachers with lessons of love beginning in utero.

Land and resources were often managed and distributed by Indigenous women. Inheritance, wealth, power, culture and history were passed on to successive generations through women. Women were integral to the traditional Indigenous way of life.

But, their roles were changed when Europeans arrived. In order to secure ownership of the New World’s resource rich land, Europeans intentionally undermined the power and authority of Indigenous women.

The Indian Act, passed in 1876, is a paternalistic government policy put in place to assimilate First Nations people through enfranchisement, a legal process for terminating a person’s Indian status in order to impose full Canadian citizenship upon them. Most often, this citizenship was executed without consent. Metis and Inuit peoples are exempt from the Indian Act.

This act gave government agents the power to enforce government policy that controlled virtually every aspect of the lives of registered First Nations people and the reserves they were forced to live on. These powers included registering births and marriages; establishing who was eligible for status; and enforcing punishments when imposed rules were disobeyed.

First Nations women have suffered, and continue to suffer, great inequalities under this federal law. They have been enfranchised for getting a university education; becoming a doctor, lawyer or member of the clergy; leaving their reserve to seek employment or escape an abusive situation; marrying non-First Nations men; becoming widowed; or being abandoned by their husbands.

Many First Nations laws allowed for divorce, but government agents had the authority to charge a First Nations woman with bigamy if she divorced and moved in with a new husband. Government agents could also impose punishments like sending the offending woman to a reformatory. In this role, government agents were the administrators of imposed colonial morality.

Dependence of First Nations women on First Nations men was legislated into being in 1851 when the federal government established that to be considered First Nations you had to be male, be the child of a male, or be married to a male.

First Nations women became non-entities and had their independence stolen from them because status would forever be dependent upon having a prescribed relationship with a First Nations male. This doctrine gave birth to the terms status and non-status.

Should a First Nations woman lose her status, then she would be denied treaty benefits; health benefits; the rights to live on reserve, inherit family property, and even be buried on the reserve with her ancestors.

If a First Nations woman married a First Nations man from another band she forfeited her right to remain in her band and was forced to join her husband’s band. This put an end to maternal lineage.

Division of property and inheritance under the Indian Act ensured First Nations women could not possess land or marital property unless widowed. Even widows were prohibited from inheriting their husband’s personal property unless deemed of good moral character by the government agent.

To this day, First Nations men retain exclusive rights to property even when relationships end. This has a tremendous impact on First Nations women and their children living with, leaving, or healing from abusive relationships.

Political involvement of First Nations women was denied when the federal government created male centric band governments preventing women from becoming chiefs or band councilors. This meant First Nations women were prohibited from providing input into decisions affecting them, their families, and their communities. Dissenters were jailed.

It was 1951 before First Nations women were allowed to vote in band elections. It wasn’t until 1960 that First Nations women and men were allowed to vote federally in Canadian elections.

Effectively, the Canadian government relegated First Nations women to non-person status, which in turn led to their disposability. This non-person status extended to Inuit and Metis women and girls as well. The inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIW) and girls is an epic undertaking. Canada has one opportunity to thoroughly understand the effect imposed disenfranchisement, under the name and guise of enfranchisement, has had on Indigenous women and girls. Unfortunately, the inquiry process has been extensively flawed and there is little hope at present that it will fulfill its mandate.

From the 1870s Indigenous children were routinely removed from their parents care to attend residential schools. Generally, children were taken at five years of age and were released when they reached 18 years of age. Over 150,000 stolen Indigenous children attended these institutions until the last school closed in 1996.

Indigenous children were exposed to physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuses. The cruelty included isolation from family and siblings, as well as torture. Deprived of the love of their parents, these children were robbed of the opportunity to learn how to become loving partners and parents. Denied interaction with their brothers and sisters, they were robbed of a lifetime of familial love and support. The injurious effects of this assimilation policy are still very much with us today.

Government agents also had the power to remove Indigenous children from their families if they were being exposed to outlawed cultural practices. Singing traditional songs, dancing, attending potlatches, and practicing their spiritual beliefs were all reason enough to remove children.

The Sixties Scoop overlapped with the residential school system. Child protection services were given the authority to “scoop up” Indigenous children and place them in non-Indigenous foster homes. This policy also allowed non-Indigenous families to adopt the children. Beginning in the 1960s this practice continued until the late 1980s.

According to Cindy Blackstock, Executive Director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, more than three times the number of Indigenous children are placed in state care today than at the height of residential school operations. The practice continues under a different name and disguise.

Part of this can be attributed to the fact that First Nations children are unable to receive the same services while living on reserve that children across Canada take for granted. In order to receive services First Nations children must be apprehended and fostered off reserve often with non-First Nations families.

Acknowledge genocide

The International Convention of the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide on December 9, 1948 set the United Nations definition of genocide as any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group:

- Killing members of the group.

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group.

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part more.

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Using this genocide checklist, Canada is five for five.

Yes, the terms cultural genocide and genocide need to be used when referring to Canada’s treatment of Indigenous people because Canada has a clearly established history of persistent attempts to eradicate Indigenous populations.

So, instead of celebrating Canada’s 150th birthday I plan to become an ally of my Indigenous sisters and brothers. But, in order to do that I’ll need historically accurate information to better inform my actions and instructions from members of Indigenous communities of how I can best assist them.

May 5 was the official launch of Aabiziingwashi (Wide Awake): NFB Indigenous Cinema on Tour: “Meaning ‘wide awake’ or ‘unable to sleep’ in Anishinaabe, Aabiziingwashi uses the power of cinema as a universal language, to build new understandings and connections between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.”

Throughout 2017, the NFB is making over 250 Indigenous-made works available for free public screenings. Stories told by First Nations, Inuit and Metis filmmakers from across the country are guaranteed to change your view of Canada’s colonial history forever. And, that’s a good thing.

The lineup includes essential films like Alanis Obomsawin’s Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) which documents the story of the 1990 confrontation in Kanehsatake, Quebec. Obomsawin spent 78 days and nights filming the armed stand-off between the Mohawks, the Quebec police and the Canadian army. See the story that was kept from the public by a variety of levels of government that interfered with media coverage while blatantly distorting the truth.

To understand how very little life has improved for Indigenous people be sure to see Obomsawin’s 2016 film We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice. This film will have you in tears, livid at Harper’s government and eventually hopeful that a change in government will end an incomprehensively diabolical funding model that denies children on reserve access to much needed services. Unfortunately, our hope is predictably in vain as Justin Trudeau’s government continues to make the same mistake — but this time it’s clearly a choice and that makes it viler.

Despite winning a nine-year legal battle, children on reserve still wait for essential services because the Trudeau government has not implemented the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal’s recommendations. Obomsawin foresaw this outcome and has just completed a documentary called Norway House (fall 2017 release) about Jordan’s Principle dealing with payment disputes within and between federal and provincial governments over services for First Nations children. Obomsawin is also at work on a follow-up to We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice.

This River (2016), a 20-minute film by Katherena Vermette and Erica MacPherson, follows the spiritually and emotionally challenging work performed by volunteers of Drag the Red, an organization based in Winnipeg.

Drag the Red was organized to shame the Winnipeg Police Service into searching for missing Indigenous women and men. Instead, Drag the Red continues to drag the Red River on a daily basis from May to October. Ground crews search the riverbanks weekly.

Two Worlds Colliding (2004) is an inquiry into what came to be known as Saskatoon’s infamous “freezing deaths.” Indigenous men were routinely driven out of town by police officers and left to walk back in minus 20 degree Fahrenheit weather without their coats or shoes. Many never made it home.

Atanarjuat the Fast Runner (2000) is a drama set in Igloolik, Nunavut, that replaces stereotypes like those found in Nanook of the North with legitimate life experiences. Filmed in Inuktitut with English subtitles it’s the quintessential Canadian film.

The NFB worked in partnership with an Indigenous advisory group to plan the Aabiziingwashi tour. This group is composed of some of the country’s leaders in Indigenous cinema: Alanis Obomsawin (Cultural Attaché, First Nations, and Producer-Director, NFB), Jesse Wente (Director of Film Programmes, TIFF Bell Lightbox), Monika Ille (Executive Director of Programming and Scheduling, APTN), Denise Bolduc (Creative Director, Producer, Programmer), Jason Ryle (Artistic Director, imagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival), and Nadine St-Louis (Executive Director, Sacred Fire Productions).

Groups interested in organizing a screening in their community can contact the NFB. For a complete and up-to-date list of screenings, visit nfb.ca/wideawake. Many of the films are available for viewing on the NFB website.

Reconciliation before celebration

Canadians tend to overlook the fact this country was born from treaties with Indigenous peoples. They are legally binding agreements between sovereign nations and have no best before date. Unfortunately, some Canadians choose to believe, and mistakenly promote the idea, that our Indigenous sisters and brothers want more than was provided for in these legally binding negotiations. The truth is, the Canadian government continually fails to live up to its obligations outlined in these covenants.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation has put together a booklet called Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action. The booklet is divided into three sections: the ten principles of reconciliation; the 94 calls to action; and the 46 articles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

Taken together these documents will help begin repairing the relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada. The calls to action are specific actions that need to be undertaken to redress the residential school legacy and promote reconciliation. UNDRIP establishes and maintains mutual respect between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Canada.

Whether you’re celebrating Canada 150 + or choosing to simply acknowledge it while focusing on encouraging Canada and Canadians to undertake impactful reconciliation, do yourself a favour and read, watch, or listen to an Indigenous viewpoint each week for the rest of the year. It’s time to not only become an ally of the first inhabitants of this great land, but to work towards meaningful reconciliation with the true founding nations of this land. Then, I will have something to celebrate.

A version of this article originally appeared in the June edition of The Anvil, a quarterly paper from Hamilton, Ontario

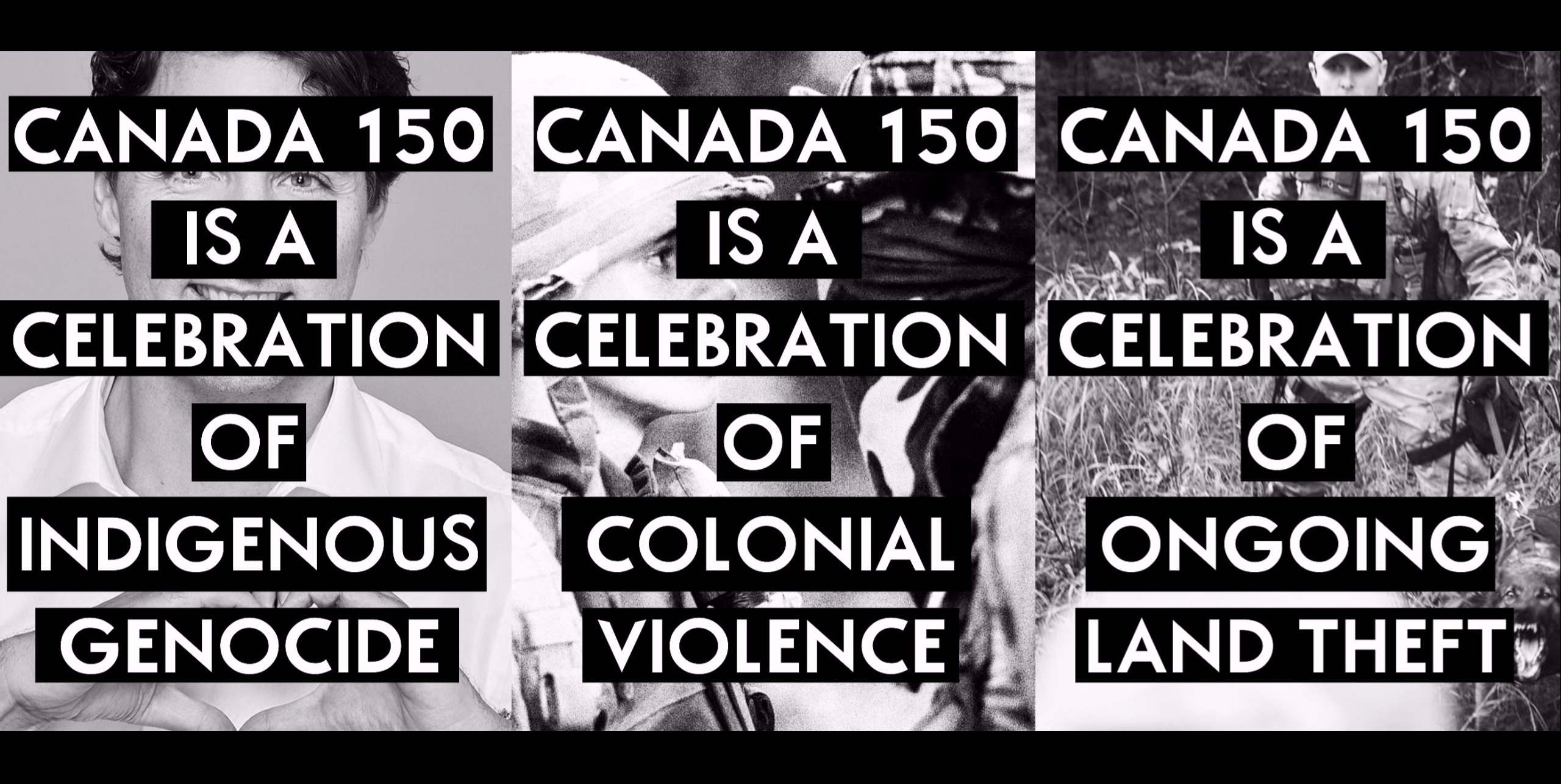

Image: Anti-Canada 150 Poster Pack

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism.