Where I last left off (here), day one of the World Social Forum had just concluded to some confusion, and the beginning of some promising talks. The second day I arrived a good bit late, after ditching the bus snarled in traffic and walking the last kilometre in the morning heat. I arrived at the session I had initially thought I wanted to attend on carbon trading, a topic I was familiar with, but found it woefully under attended for it to really advance the issue. I instead decided to check out another session across the campus, along the way running into Tom Goldtooth, director of the Indigenous Environmental Network, the organization I was representing at the forum. He asked me to present on a panel he wasn’t able to attend, on the significance of Indigenous participation in this year’s forum. So I happened over to search for the room, but upon entering the room scheduled for this debate, I found a Brazilian political party had instead occupied the room. It would take me over 20 frustrating minutes to find the correct information and get over to the right room. In the end we still had to wait half an hour for the political party to finish before we could start our talk. I also ended up being the only person able to translate into Spanish, so that was my second role during the discussion.

The discussion was crucial and challenging. Presenting were myself, two representatives from the Andes, and one from Indian forest peoples, moderated by a brilliant and tactful researcher from India. A number of criticisms and critiques of the World Social Forum process emerged, which I will attempt to resume here. From the outset, there was little Indigenous involvement in the planning process, despite claims that this WSF was an Indigenous-led process. Even with all the outreach, there was still a lack of understanding of Indigenous values and worldviews even among the main WSF planners, who were from a mainly Eurocentric background, it seemed. There were a number of actions over the course of the forum that were offensive to the Indigenous representatives, from disrespectful actions toward Indigenous leaders from the Amazon, to the promotion of some (nationalistic) projects like dams in Brazil that had been violently opposed by the same Indigenous groups the WSF was claiming to be led by. The WSF had also been extremely slow in acknowledging how Indigenous movements were in fact leading the anti-globalization movement in many places, from the Zapatistas in Mexico to the huge mobilizations that have stopped countries like Colombia, Ecuador and Bolivia. This has led to something like the exploitation of the Indigenous Peoples present, who were on the covers of all the documents and media reports, but rarely found giving their opinions. These were the most significant charges levied against the World Social Forum, but fortunately could be addressed if the WSFers believed them to be a priority.

The next morning the Indigenous Environmental Network had two sessions in a row focused around Climate Justice and Indigenous Peoples. Topics covered included carbon trading, Indigenous rights, ecological debt, biofuels impacts, etcetera. One chief from British Guinea made an impassioned plea for Western society to radically alter its course to be able to save his people that touched everyone deeply. A representative of the Landless Worker’s Movement (MST) talked about their experience with how badly designed conservation projects were being implemented in Brazil at great social and environmental expense, a similar situation from Biofuels harvesting. Other analysts talked about the injustices faced with carbon trading, giving the responsibility to deal with climate change to developing countries, and passing off the ‘externalities’ to the poorest communities, while not dealing with the fundamental causes of climate change. Tom Goldtooth was able to weave many of these elements into an Indigenous perspective, as well as a global perspective that showed the extent of the problems mentioned. I later went on to talk about the Tar Sands in Canada, an active campaign of the Indigenous Environmental Network, discussing not only the massive environmental but also social and Indigenous rights impacts caused by the megaproject, which is always a surprise to many people internationally, who think Canada is such a green giant. Many parallels were drawn with the last presenter, an Indigenous representative from Nigeria, who talked about the massive oil developments within their country and their people’s lands. We had a good turnout, and one guy filming the session throughout, and that was most of what I did for the day.

Day 4, January 31st, was the last day of official meetings, and the day many in our networks had been anticipating. There was a planned meeting between Indigenous representatives and environmentalists, and many of each showed up. The session turned out to be greatly useful to discussing common causes, as well as how Indigenous Peoples’ were understanding and framing contemporary issues like climate change and deforestation, which had only recently become of concern to mainstream society, now that it threatened their survival. This was seen to represent a failure of western civilization, as well as many movements around the world to rally behind Indigenous Peoples’ concerns in their relationship with the Earth. More concretely, many of the contributions focused on coming together around climate change, and the need to push environmental movements the world over to critically look at how their actions were impacting Indigenous Peoples. There was also a proposal coming from the Andean peoples that October 12th, celebrated as Colombus Day in some places, a solemn occasion for many others, this year should be a worldwide rally for Indigenous Peoples and the Protection of Abya Yala (Mother Earth). Many people stayed talking for a long while after the session ended, which seemed to be the point of much of the World Social Forum, in terms of bringing people from such diverse backgrounds into one physical space.

While attempting to make the 30 minute trek across campus to another session, I ended up first finding myself part of an unprovoked rally, in support of a cause I was never fully sure of (I think maybe marijuana). After distracting myself taking some photos, I wandered over to the Indigenous tent for a while to say goodbye to some friends from the Amazon, who would begin their week-long trek on boat and foot back to their villages the next day, as well as to some friends from Chad and Kenya who were also about to depart. After listening to the concluding panel of the Indigenous Peoples’ tent, I was about to leave for my home when I ran into an old friend, a statistical improbability in this veritable sea of people. She was a representative of the Baloch people of Iran, who I had met at a UN meeting on Indigenous Peoples. We spent a few minutes catching up, before I departed to come back for the closing ceremony the following day.

The last day I arrived late, partly the result of another torrential rainstorm which likely caused many to stay home that day. Instead, I waded through six inches of water flowing in front of the house, my pants rolled up but still soaked, with an umbrella mostly to keep my camera dry in my backpack. In the end, I wasn’t sure it was worth the trek. I eventally made it to the site, but didn’t stop at the main pavilion when I arrived, instead checking out the youth camp for the first time, trying to gain a sense over how much this gathering may have resembled something like Woodstock. In the end, I concluded the campground was pretty tidy, not many drugs were hanging in the air, and there was only one gratuitous display of nudity, in front of an ‘eco-porn’ display. I got back to the pavilion just in time to hear the Indigenous speech. What was happening for the closing was that each of the working groups were given time to present a final speech and list of recommendations. The Indigenous speech was broad but penetrating, and included the October 12th day as its main concrete action. Other speeches came from the Palestinian committee, the group on immigration, a group about nuclear disarmament, and many others. All told, though, there were hardly more than a hundred people there, out of the supposed 100, 000 attending the forum, and there was little translation provided for many of the speeches, either in Portuguese or Spanish. In the end, I left before it was done, to spend the evening with the family who was hosting me.

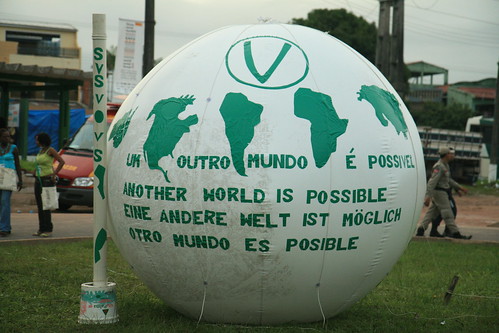

It was a bit of a shock to be thrown back into ‘civilian’ life so quickly, and I don’t think I was ready for it. The family wanted to first stop by a local mall to pick up a replacement cell phone for one that had gotten soaked. The sudden shock of so much capitalist superficiality in one place, coming directly from the ‘World Forum of Socialists,’ as one friend put it, was a stark reminded of how much change was needed in the world. All of a sudden, we were in the centre of a symbol of the exact opposite of the seeming values of the WSF, but alone, which is what I realized the partial power of the WSF holds – to bring so many people and movements together, and let them know that around the world, they are indeed committed to the same goals, from building worker movements, to agrarian reform, to finding autonomy for Indigenous nations, to replacing the political-economic system. This was the movement struggling to come alive through the WSF, one that you could barely make out, through all the overlapping activities and raucous debates. This was where its power lay, in the hands of the many people represented at the forum, as well as the decent people and families like the one who hosted me, who only hoped for a better world.

The next day, after the forum was over, I had the chance to also participate in the International Council meeting of the World Social Forum, basically gathering about 150 representatives of different social movements and NGOs from around the world to evaluate and plan for the next WSF. Notably lacking were Indigenous representatives, as there were only maybe three of us in the room, and none from Brazil, which was a huge issue. In fact, we were unable to speak, being non-voting members, so we were only able to get one voting member to speak some of the concerns I mentioned above, on our behalf, in the middle of much self-congratulations on promoting Indigenous causes. After dealing with the evaluation of the current WSF, I enjoyed lunch with members of the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance and a Palestinian activist from www.stopthewall.org.

After lunch, the meetings broke down, as the talk shifted to the next forum. Not only were there not enough headsets, the translation was missing for many people with headsets, and this took a long time to fix. The discussions almost turned into a yelling match as members argued over whether the decision over the next venue being in Africa had already been decided, and whether this was an underhanded attempt to evade that decision. Eventually the talks were postponed until the next day, which would have marked the 12th straight day of meetings had I decided to attend. Instead of showing up to listen from the sidelines as a bunch of old men yelled at each other, I decided to visit some botanical gardens and parks within the city on my last day in Brazil. Seemed like the revolution still needed to work on its inclusivity and representation.

More photos are available at: http://www.flickr.com/photos/powless/sets/72157613219715414/