Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

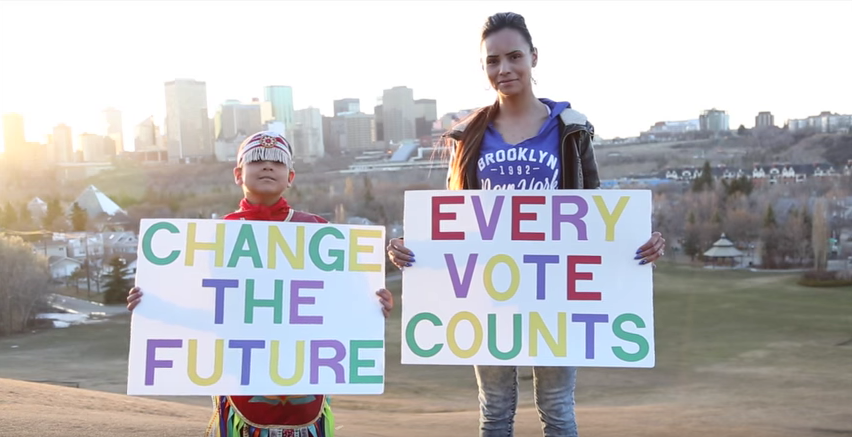

During last year’s federal election, the Assembly of First Nations raised the issue of disengaged Indigenous voters, and indeed, “Rock the Vote” and other campaigns earned the issue plenty of traction in the media. Indigenous voter turnout increased notably during last year’s federal election.

Advocates of proportional representation (PR) often tout electoral reform as a legislative fix that will increase voter turnout among groups that traditionally vote at lower levels (like youth, for example).

However, Indigenous voter turnout is a different matter. Increasing Indigenous turnout is a multifaceted task that goes beyond simply altering the type of electoral system in place.

Legacy of colonial oppression and disenfranchisement

Government and academic researchers have scrutinized the institutional legitimacy of the electoral system in a colonial context — specifically the way Indigenous people have disengaged or refrained from voting altogether.

However, Indigenous people are far from politically disengaged. Indigenous people are extremely active in local and community-based politics where the impact of participation is more readily obvious.

At the federal and provincial levels, centuries of oppression and disenfranchisement prevented Indigenous involvement in Canadian electoral politics. The full franchise was not extended to all Indigenous voters until 1960.

The restrictions placed on the Indigenous right to vote have led to a historical lack of Indigenous political representation in Canadian governments. Alienation is not a surprising result; and indeed, some Indigenous people consider voting in Canadian elections tantamount to condoning or excusing past colonial policies.

Ultimately, Indigenous electoral disengagement is rooted in this discrimination and economic marginalization, which have perpetuated alienation and discouraged Indigenous people from participating in Canadian electoral institutions.

Lower Indigenous turnout in Canadian elections is not simply due to apathy or alienation, as is often the case among other cohorts. Rather, historical, cultural and attitudinal differences impact the extent to which some Indigenous community members and leaders embrace voting in Canadian elections. And there is variation from one community to the next.

Pure PR arguably constitutes the most significant or extensive reform to our electoral system, and thus may be harder to implement, given widespread change and potential resistance from stakeholders such as government and the public.

Previous attempts at electoral reform in Ontario, British Columbia and P.E.I. failed for a similar reason, despite the fact that suggested reforms in these cases were not as extensive as PR.

There are alternatives that might improve Indigenous turnout.

At the most basic level, electoral representation could increase the number of Indigenous members of Parliament, representatives in provincial legislative assemblies, or appointed senators. The goal is to promote Indigenous connectedness to federal and provincial electoral politics through improved representation, thus increasing voter turnout.

Can PR actually increase Indigenous turnout?

Improving representation would require more opportunities for nomination of Indigenous candidates in the main political parties, along with encouraging Indigenous involvement in party policy and decision-making.

Such attempts were made in the most recent federal election, mainly with the Liberal Party and New Democratic Party, and arguably played a role in the overall increase in Indigenous voter turnout.

Other jurisdictions outside of Canada have sought to increase Indigenous turnout through widespread electoral system change. For example, New Zealand’s Royal Commission on the Electoral System, followed by referendums in 1992 and 1993, led to a change from FPTP to mixed-member proportional (MMP).

In the elections following the reforms, Maori representation increased, but Maori voter turnout did not. Instead, overall turnout actually decreased further. Similar results on Indigenous turnout have occurred elsewhere (like the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission), and thus call into question the usefulness of PR for increasing Indigenous turnout.

Instead, mechanisms that add specific, guaranteed Indigenous representation to existing electoral systems may be more effective. Such approaches would not mandate fundamental electoral change either. Guaranteed Indigenous seats, affirmative redistricting, Aboriginal electoral districts (AEDs) and Indigenous legislatures have all been tried elsewhere with varying degrees of success.

But guaranteed Maori seats in New Zealand’s Parliament have done little to increase Maori turnout because these seats are largely symbolic. Affirmative redistricting is similar, but does not require the creation of new seats for Indigenous representatives. Instead, existing electoral districts are adjusted to provide more concentrated Indigenous populations to increase the likelihood of Indigenous representation.

Representation without real power is not enough

During the most recent Canadian federal campaign, the AFN specifically focused on those ridings where Indigenous populations are much larger. AEDs consist of electors who identify as members of First Nations, Inuit or Métis, with regional residence as a secondary consideration. AEDs overlap or are superimposed upon geographic districts. Specific voters lists would be created, the number of districts would be up for debate, and the heterogeneous nature of Indigenous peoples would have to be considered when determining districts.

Indigenous parliaments or legislatures could take an advisory role in the House of Commons and Senate on matters relating to Indigenous people. Voters would elect representatives from their respective nations — but is this sufficient? There are Saami parliaments in Finland, Norway and Sweden, but without any legislative functions, their power is severely limited.

Instead, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples asserted the need for a robust Indigenous Parliament where “Indigenous peoples can be fully involved, if not primarily responsible, for the structure and processes of such institutions.”

Guaranteed representation may lead to some increase in Indigenous turnout in Canadian elections, but these approaches do not address Indigenous nationalism. Improving Indigenous representation without Indigenous input is not a legitimate means to increase Indigenous voter turnout. Some Indigenous people will continue to view the Canadian electoral system as foreign impositions and representations of colonialism and historical dispossession.

There should be formal and explicit recognition of Indigenous peoples as nations who are culturally distinct from the rest of Canada. Quite apart from the type of electoral system at the federal or provincial levels in Canada, recognition of Indigenous nationalism as a vibrant and foundational component of Canadian society and electoral politics is crucial.

In this vein, Canada must officially recognize Indigenous nations in order to bridge the gap of alienation and help move toward reconciliation. Such recognition is a fundamental first step in improving Indigenous voter turnout in Canada.

Interested in contributing to this series on proportional representation? Send us a pitch to [email protected] with the title “Proportional representation series”

Part 1: Proportional representation is not ‘too complicated’ — the fix is in

Part 2: Activists gear up for ‘historic opportunity’ to usher in proportional representation

Part 3: Proportional representation for Canada: A primer

Dr. Jennifer E. Dalton is a Senior Research Associate at The Conference Board of Canada. The views expressed here are her own. She is a seventh-generation Canadian of Scottish, English, French-Canadian, Mohawk (Kanien’kehá:ka of the Six Nations of the Grand River Territory), Métis and Innu (Montagnais) ancestry. Follow her on Twitter @DrJEDalton.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Image: YouTube/Young Medicine